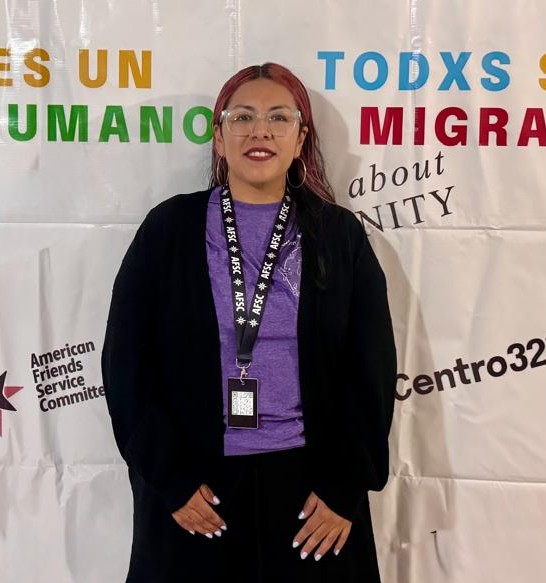

As part of the Cutting the Patriarchy project, migrant women develop haircutting skills while also learning about gender-based violence. Emely Arroyo and Jocelín Mariscal

I am writing from the city of Tijuana. In Mexico, people say that the homeland begins here, but here something else also ends or begins—sometimes dreams, sometimes realities—and this is especially true for migrants. Tijuana is located in northern Mexico, bordering the United States; I live in a border region marked not only by a wall but also by expressions of solidarity, opportunity, and, at the same time, racism and discrimination.

At this corner of Mexico, migrants from every imaginable part of the world arrive for a variety of reasons, most of them heartbreaking. My work as a migration program officer at AFSC has taught me that although it is difficult to hold on to the hope that things can be better for the people we serve, sometimes a simple gesture—like serving a cup of coffee—can change the course of a life.

I want to share a story with you. In 2024, we launched a program in Tijuana called “Cutting the Patriarchy” that aimed to teach haircutting techniques to migrant women while also sparking conversations about their rights and gender-based violence. Our workshops were held at a shelter.

On the first day, two dozen migrant women, curious about what was to come, attended. One of them, María—a 60-year-old who had been living in the shelter for five months—approached me and said, “I don’t know how to do anything. I’m too old and can’t learn anything anymore, but they told me that in this workshop they would serve coffee, so I’m here. Can I come just for the coffee and drink it while I watch the workshop?” I, of course, said yes.

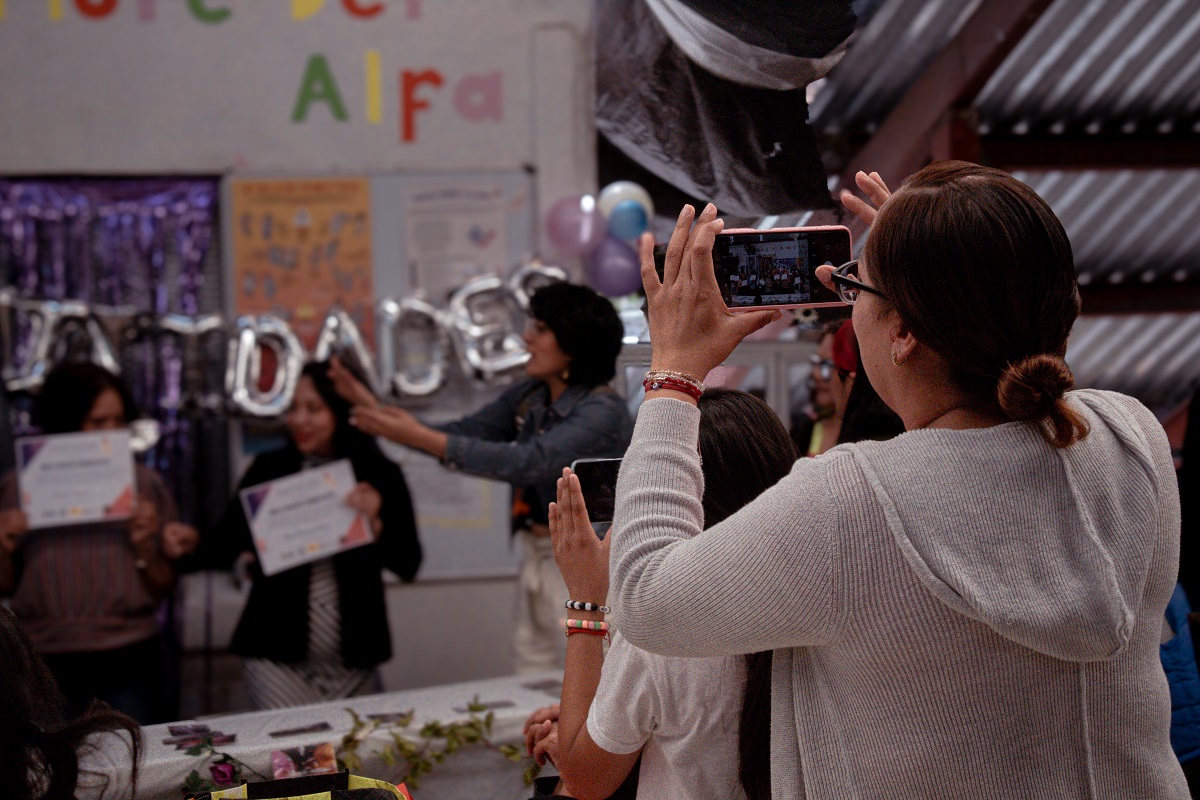

A participant cuts hair at the shelter where the Cutting the Patriarchy classes are held. Emely Arroyo and Jocelín Mariscal

As the days went by, while having her coffee, she shared that she had been waiting five months to enter the U.S. She had scheduled an appointment to enter the U.S. using the CBP One app* and had to reapply because her record had been “erased” without explanation.

Maria had come from the state of Guerrero, from a community co-opted by organized crime. She never learned to read or write, worked her entire life cleaning houses, and for half of that time she suffered domestic violence. With no other options, she had to flee and travel 3,000 kilometers by bus—facing extortion and other abuses—until she reached Tijuana, the farthest anyone had ever told her she could go.

María is Mexican, so she could work in Mexico. However, she faced other barriers: fear of becoming a victim of violence, discrimination due to her age, her inability to read or write, and not having a permanent address. Her case is one of thousands of internally displaced women who have been forced to migrate by a system that has excluded them, failed to protect them from the many forms of violence they face, and neglected to provide them with opportunities to build better lives.

María kept coming to our workshops, each day with a different question, often skeptical. One day she asked me if it was truly possible to live a life free from violence, as we had discussed in one of our gatherings, which we called the “circles of words.” She became interested in learning about her rights and the rights of her family. She especially wanted to understand what that “strange word”—patriarchy—meant.

A few weeks later, before having her coffee, she approached me to ask, in a whisper, if I believed that she could learn to cut hair. Of course, I encouraged her. That day she fully participated in the workshop and started attending every class. Eventually, she graduated. She and her family were overjoyed. “I’m a stylist!” she exclaimed.

Participants graduate from the weekslong Cutting the Patriarchy course. Emely Arroyo and Jocelín Mariscal

María’s story is one of success and hope. AFSC played a small part in convincing her of her value and abilities. For me, as someone who accompanied her through the process, the greatest gift was seeing her smile, question her reality, learn new skills she could take with her wherever she went, and recognize her rights.

Although the obstacles María has faced differ from mine, as a woman I relate to her frustration and fears because my life is also full of challenges—living in a country where machismo remains prevalent and where I have to work even harder to be recognized as a professional, a mother, and a human being. Still, people like María inspire me and give meaning to my work. In the end, María kept saying that she was only there for the coffee, but undoubtedly, she left with so much more—and so did I.

*Under the Biden administration, the CBP One app allowed migrants to schedule appointments to seek asylum at ports of entry. It was shut down by the Trump administration soon after taking office.