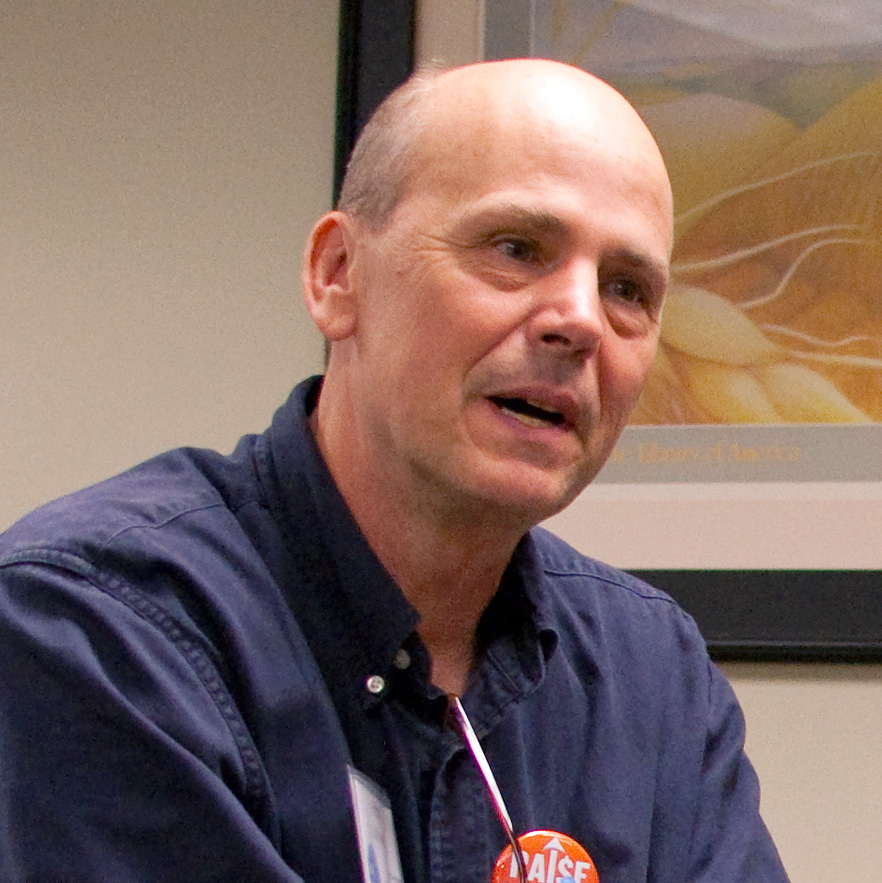

Walter Reuther at a labor rally. Public domain

The head of the United Auto Workers was also an advocate for peace, civil rights, and the environment.

One of my favorite parts of the Bible didn't make it into most Protestant versions. It's from Ecclesiasticus, a Jewish wisdom book along the line of Proverbs. This selection is read on All Saints' Day in some churches.

“Let us now praise famous men, and our fathers in their generation. The Lord apportioned them to great glory, his majesty from the beginning. There were those who ruled in their kingdoms, and were men renowned for their power, giving counsel by their understanding, and proclaiming prophecies; leaders of the people in deliberations and in understanding of learning for the people, wise in their words of instruction ... all these were honored in their generations, and were the glory of their times. There are some of them who have left a name, so that men declare their praise. And there are some who have no memorial, who have perished as though they had not lived. ... But these were men of mercy, whose righteous deeds have not been forgotten; their prosperity will remain with their descendants, and their inheritance to their children's children. ... Their bodies were buried in peace, and their name lives to all generations. Peoples will declare their wisdom, and the congregation proclaims their praise.”

I am quoting all this because there is a famous man I want to praise on this Labor Day, and I don't know any better way of starting. He was a native son of West Virginia and is still honored for his life and deeds more than 45 years after his death.

He was never elected to public office, although he advised several presidents and helped shape national policy. He was not a war hero, although he was on various occasions beaten, shot, and otherwise menaced for standing up for his beliefs. Most importantly, he helped to make life better for literally millions of people in very concrete ways.

His name was Walter Reuther, son of Valentine and Anna Stocker Reuther, and he was born in Wheeling in 1907. His father was a union worker, a democratic socialist, and an admirer of Eugene Debs. From his parents, he inherited a vision of solidarity, democracy, and social justice that he would put into practice throughout his life. As he put it, "There is no greater calling than to serve your fellow men. There is no greater contribution than to help the weak. There is no greater satisfaction than to have done it well."

His name was Walter Reuther, son of Valentine and Anna Stocker Reuther, and he was born in Wheeling in 1907. His father was a union worker, a democratic socialist, and an admirer of Eugene Debs. From his parents, he inherited a vision of solidarity, democracy, and social justice that he would put into practice throughout his life. As he put it, "There is no greater calling than to serve your fellow men. There is no greater contribution than to help the weak. There is no greater satisfaction than to have done it well."

After dropping out of school at age 16, Reuther became an apprentice tool and die maker and soon headed to Detroit to work in the auto industry. Along with his brothers, Victor and Roy, he became active in building the newly formed United Automobile Workers.

The UAW was a branch of the newly formed Committee on Industrial Organization or CIO (later known as the Congress of Industrial Organizations). The CIO was a brainchild of John L. Lewis, the legendary United Mine Workers leader who broke with the American Federation of Labor over its failure to organize workers in the mass production industries such as textiles, automobiles, steel, and rubber.

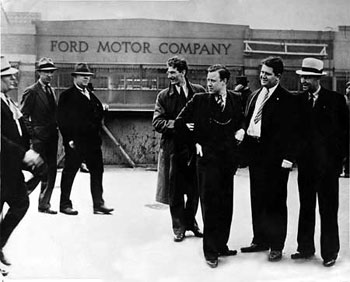

Reuther played a key role in planning the successful sit-down strike against General Motors. He was beaten bloody by Ford security guards in the famous 1937 "Battle of the Overpass." In time, Ford too recognized the UAW. The union brought vast improvements in wages and conditions and industrial democracy to tens of thousands of workers.

A lifetime opponent of all forms of fascism and totalitarianism, he urged the auto industry to refocus its efforts on the defeat of the Axis powers, a step some industrialists opposed. He became an adviser and eventually a friend to President Franklin Roosevelt and first lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

In 1946, Reuther became president of the UAW, an office he held until his death in 1970. In 1952, he became the leader of the CIO and worked for its merger with the AFL. His approach to the labor movement has sometimes been called social unionism. He believed its task was to "fight for the welfare of the public at large," rather than exclusively for improving conditions for its members. A favorite slogan of his was "Progress with the Community -- Not at the Expense of the Community."

He was as good as his word. He advocated for universal health care, full-employment policies, a national minimum wage, federal aid for housing, anti-poverty programs, and a host of other issues. He also was active in environmental causes, particularly those related to the pollution of the Great Lakes.

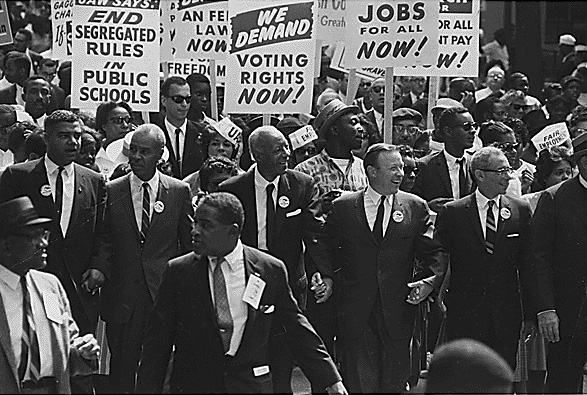

Reuther personally and the UAW as an organization were key financial, moral, and political supporters of the Civil Rights Movement. He shared the podium with Dr. Martin Luther King at the famous March on Washington in 1963, when King gave his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. According to one anecdote from the march, two elderly women were standing close to the podium. When Reuther was introduced, one of them asked who he was. The answer was: "He's the white Martin Luther King." Pretty close, anyway.

Reuther also lent support to nonviolent campaigns of the United Farm Workers to improve conditions for predominantly Mexican-American farm laborers.

Looking back over his life, he once said, "The labor movement is about changing society. What good is a dollar an hour more in wages if your neighborhood is burning down? What good is another week's vacation if the lake you used to go to is polluted and you can't swim in it and your kids can't play in it? And what good is another hundred-dollar pension if the world goes up in atomic smoke in a war?

"I mean, don't you see that these immediate things—you can't realize them—they have no value, excepting in the context of a society and a world in which these values can be given meaning? So I don't think you have to be noble to look at it. I think it's a pretty practical way to look at the thing.

"I may be motivated because I just happen to think these values are important, and I'm willing to fight for them and I'm willing to die for them because I happen to believe in them. I've had what I think is the richest self-fulfilling kind of experience a human being can have. I have been living what I believe. I mean, can you ask for more than that?"

Since Reuther's death in 1970, the UAW, like most of the labor movement, has taken some hits in the wake of deindustrialization, corporate globalization and systematic attacks on the gains made by working people. It is now facing perhaps its most serious challenges to date, but it's still kicking.

In a time when many people are combing through the past in search of inspiration and ideas, Reuther deserves some serious attention. His vision of social unionism and broad coalition building in the interests of a more just society could help revive not only the labor movement but all efforts to move the nation in a more positive direction.

A version of this article was originally published on the author's personal blog, The Goat Rope.