When Sophia Burns was a high school student in southern New Jersey, her school implemented a policy prohibiting students from carrying water bottles or backpacks that weren’t see-through. “We were told the policy was to discourage students from carrying weapons, drugs, or alcohol,” says Sophia, who recently served as a Young Leaders for Change fellow with AFSC.

“But what it did in reality was perpetuate stereotypes about youth, always suspecting us of doing something wrong rather than addressing the real problems we deal with in our everyday lives.”

In the city of San Salvador in El Salvador, Omar Ponce says he can’t remember a time when he didn’t feel stigmatized as a young person—not just by government authorities and others in power, but also by the world outside of his country.

“Whenever you hear people talk about youth in El Salvador, they talk about crime, gangs, and violence,” says Omar, 26. “Those narratives have negative impacts on how young people see themselves and how they are treated by others in our society.”

Every day, youth around the world—particularly those who are poor and of color—experience the impacts of these harmful narratives, facing discrimination and other barriers in pursuing their education, finding jobs, or navigating interactions with authorities.

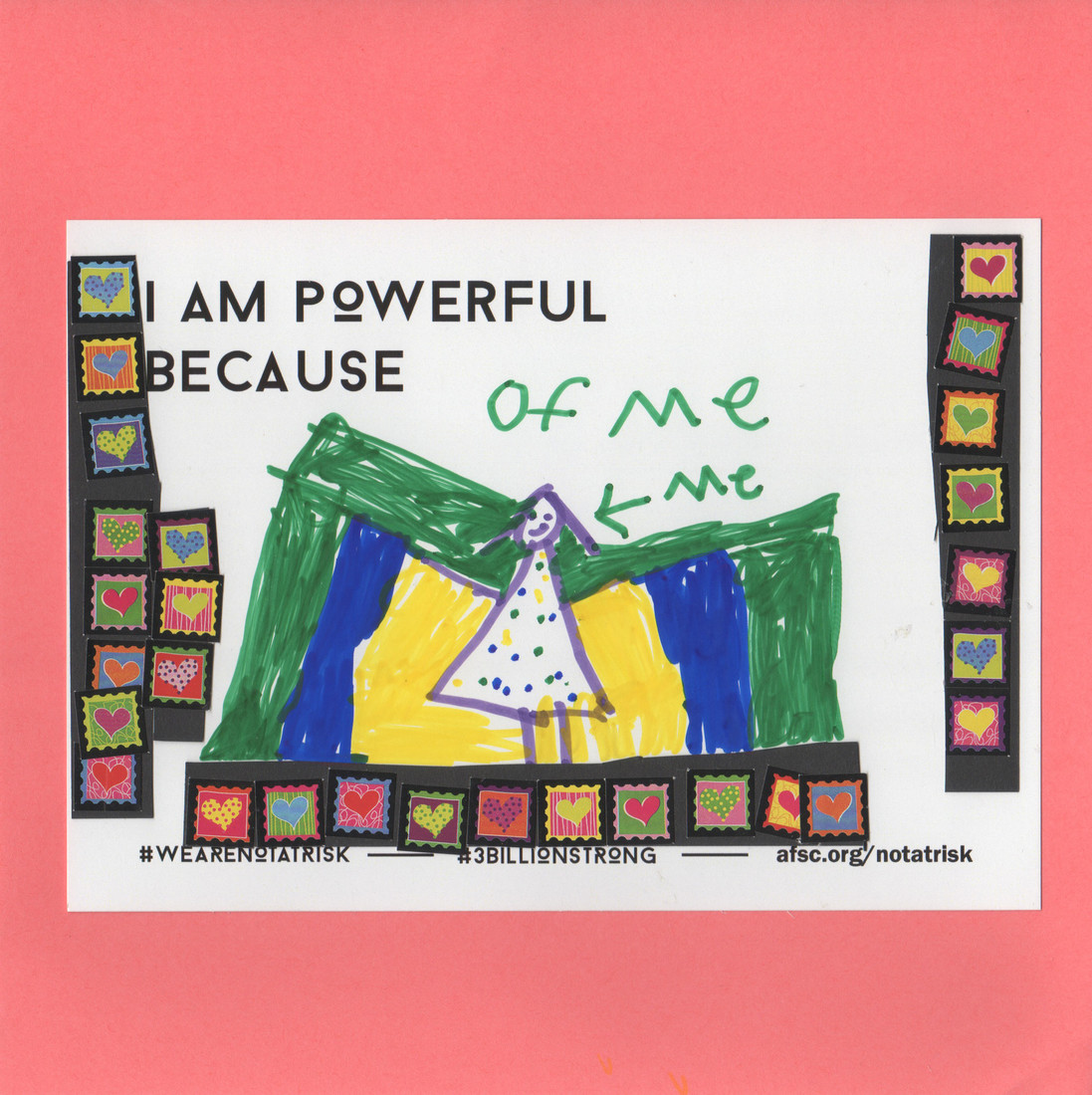

That’s why youth leaders in AFSC’s Youth in Action (YIA) global network are working together to change perceptions of youth in their respective communities. In 2018, YIA launched the “We Are Not At-Risk” social media campaign to transform the words and narratives we use to talk about youth in our everyday conversations; in schools, nonprofits, and other institutions; and in the media.

“Historically words have been used to oppress Black and brown people and help those in power maintain their power,” says Nia Eubanks-Dixon, AFSC director of youth programs. “Today, words like “at-risk,” “marginalized,” and “minority” are used for the same purposes. Not only do these terms dehumanize youth, they shift blame to young people instead of to the oppressive racist systems that exploit them, their families, and communities.”

The “We Are Not At-Risk” campaign was created to call out and change those linguistic behaviors, urging people to take a pledge to rethink their words, attend local education events, and share what they’ve learned with others.

In the campaign’s first year, more than 1,000 pledges were taken by community based organizations, faith-based institutions, and colleges. Several of them took steps to change the way they talk about youth:

In Philadelphia, the Department of Human Services agreed to adapt the language it uses in its Request for Proposals to meet the We Are Not At-Risk guidelines.

The Grants Professional Association widely distributed guidelines among its 2,800 members, sparking much-needed discussion among grant professionals.

YIA participants spoke at the National Immigrant Integration Conference, the Alliance for Peacebuilding conference, and several universities–encouraging organizations to move away from racist colonial language and work with youth to adopt new wording.

In January of this year, YIA members built on the momentum of the “We Are Not At-Risk” campaign by focusing their attention on the media. “At a time when media plays such a pronounced role in our lives, it is especially necessary to think deeply about the consequences of negative and biased representation of young people,” Sophia says.

According to one media study by Mori for Young People Now, one in three articles about youth are focused on crime or antisocial behavior. What’s more, young people were only quoted in 8% of those stories.

As part of this year’s campaign, YIA members and allies are urging media outlets, journalists, and bloggers in their communities to pledge to rethink their depictions of young people.

Youth are also providing guidance to the media on telling more well-rounded stories and organizing educational events to train students and other community members on how to talk about youth by focusing on their assets and potential.

Cherri Gregg was one journalist who was moved by the campaign. “As a journalist who covers communities that are very vulnerable—and many times mischaracterized—when I heard of a new movement to change the narrative when it comes to youth, the hairs on the back of my neck stood up,” she said during her Philadelphia-based radio show. “Over the years, I've worked hard to be very mindful of the words that I use to characterize a variety of communities.” She also instructed listeners, “At the end of the day, take a pause: Are you using stereotypes to characterize others?”

Changing how the media and our society talk about young people is a long-term effort, Sophia and Omar say. But through “We Are Not At-Risk,” more youth leaders around the globe are tapping into their power to tell their own stories—and create the future they want to see.

“Through the campaign, youth deepen their analysis of systems of oppression and their root causes, which helps us confront them more effectively,” Omar says. “We’re also engaging more partners, organizations, and allies who can support us in our resistance.”