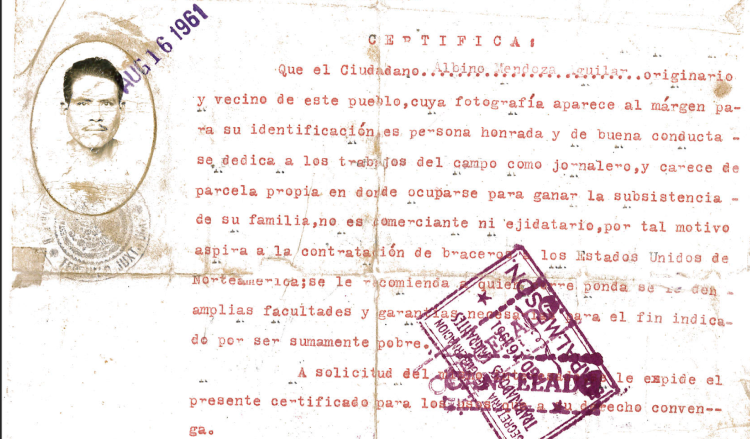

Minerva Mendoza's grandfather, Albino Mendoza Aguilar, was a Bracero. AFSC

PVI spent much of 2021 advocating for just and comprehensive immigration reform. The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 was the last immigration policy that granted permanent legal residence and eventually a path to citizenship for about 2.7 million immigrants. Since then, millions of immigrants have been waiting and organizing to regularize their status.

As with the win of any Democratic president, the Biden administration raised hopes that this could be the time to finally grant permanent residency and a path to citizenship to the more than 12 million immigrants who need to regularize their status. That hope once again is fading as we see immigration policies moving away from citizenship toward parole.

In collaboration with the Dignity Campaign, formed by a coalition of national immigrant rights organizations, we have organized advocacy actions such as the virtual presentation of the newly released book Our Grandfathers Were Braceros and We Too. Co-authored by Rosa Martha Zarate Macias and Dr. Abel Astorga Morales, and translated by Madeline Newman Ríos, this book and our presentation advocate and inform the community about the complexities of replicating programs like the Bracero Program, which was the intention of the Farm Workforce Modernization Act of 2021.

Our Grandfathers Were Braceros and We Too is a memoir of the farmworkers who participated in the Bracero Program (1942-1964). The program was designed to bring Mexican workers to fill the labor shortage due to World War II. Extended documentation tells of the labor and human rights violations the Braceros confronted. The history of this program shows the fate of temporary workers such as those currently participating in the H-2A program.

My grandfather was a Bracero

The book illustrates young Mexican men who participated in the Bracero program. One of those men was my grandfather, Albino Mendoza Aguilar, who migrated in 1961 to work in Gilroy, California. We learned about his journey through multiple letters he wrote to my grandmother.

In one of those letters, my grandfather shared that he had safely arrived in the U.S. He also guided my grandmother to spend the money he had sent her and send his blessing to his children. Like many other Braceros, my grandfather gave the best years of his to the California agricultural industry.

If you asked my grandmother, she would also say he gave his life. My grandfather died at the considerably young age of 42. My grandmother would say that his body had given up on him after all he had been through, working arduously in the fields of California, or el Norte, as they referred to it then.

As we see an increase in the number of migrants being brought to work with H-2A visas – over 250,000 people last year—we can see the importance of remembering the history of programs such as the Bracero to avoid repeating labor and human rights abuses. The new generation of immigrant rights advocates and farmworkers need to learn about earlier dangers of temporary agricultural workers programs.

We must be vigilant and cautious about these programs because they may sound like a solution, especially to our communities who are desperate for an answer, yet we must focus on long-term solutions and oppose piecemeal legislation. There is consensus among the farmworker community that programs like the Bracero Program, DACA, and TPS that do not provide a pathway to citizenship or change the immigration system are not a solution to the current migration crisis.