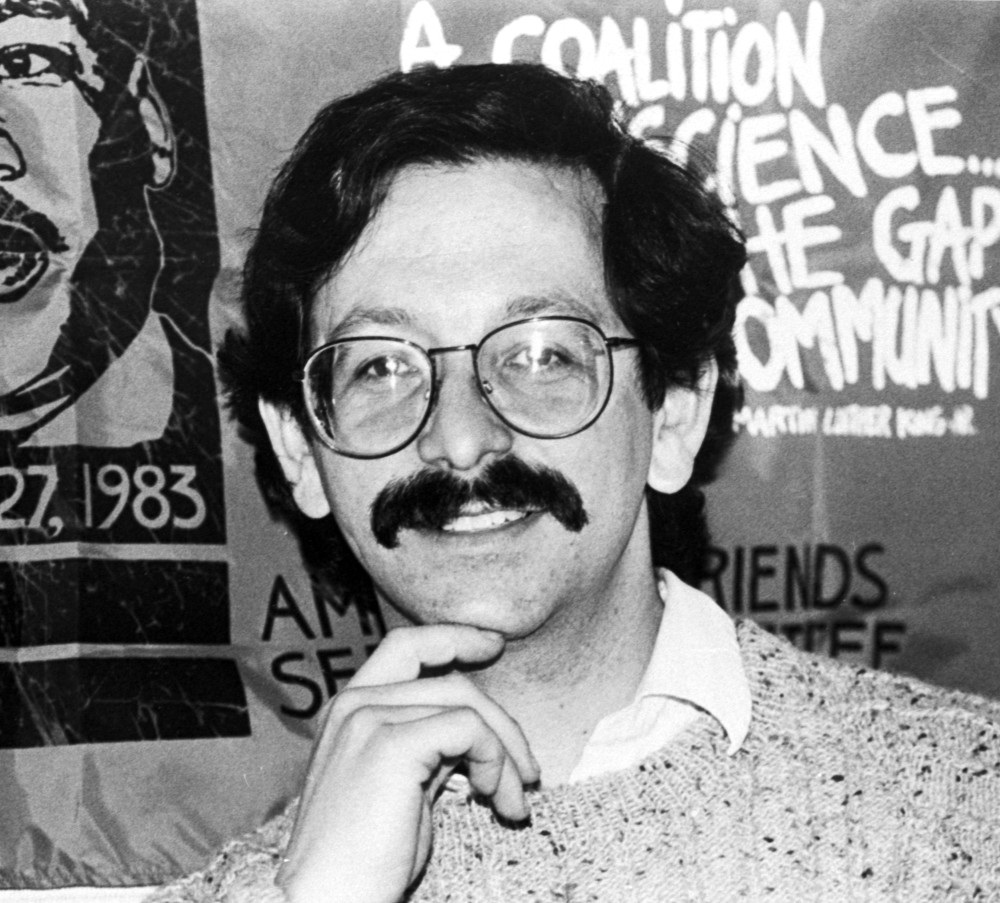

From what I heard later, my hiring in 1981 as the program coordinator for AFSC’s New Hampshire Program was not a sure thing. I was pretty well known already in the circles traveled by Quakers in New Hampshire due to my work with the Clamshell Alliance and the “No Nukes” movement. I had done some research for the NH Program on organizing possibilities relative to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, a major industrial facility that overhauled nuclear submarines. When draft registration was reinstated by Jimmy Carter in 1980, I had participated in AFSC-sponsored draft counselor training and actions at post offices. But some people thought I might not be the right person for the job.

One factor affecting my reputation was an incident from the conclusion of the 1977 occupation of the Seabrook nuclear power plant construction site. More than 1,400 people had been arrested and sent to National Guard Armories scattered across southeastern New Hampshire. I was one of a couple hundred people held at the Concord Armory, my first trip to that city.

Refusing to pay bail until we were assured that everyone would be released on their own recognizance (a promise to show up in court for arraignment), we were in a principled stand-off for nearly two weeks with the state’s ultra-right wing and ultra-pro nuke governor, Meldrim Thomson.

Finally, at the end of the second week of incarceration in the armories, the Clamshell lawyers reached a deal with the state. If everyone who was still being held would agree to accept a finding of guilty without going through arraignment and trial, we would be released without bail and able to appeal our convictions to the Superior Court, where we would get a trial by jury. It wasn’t a bad deal, but the idea that we would be marched in and out of the court and be found guilty without trial struck me as a “kangaroo court.” So, I decided to fashion a kangaroo outfit out of what little resources I had at the armory.

First, I put my long hair up in pigtails to represent ears. I made a sock puppet baby kangaroo and stuffed it in a pouch made with a bandana sewed onto my t-shirt. Suitably kangaroo’d up, with my hands curled in front of my chest, I hopped up to the doorway of the Hampton District Court. “You’ll have to leave the kangaroo outside,” said the police officer guarding the door, with a straight face and his finger pointed at my pouch. With a sad look, I passed the sock puppet to an affinity group member outside and hopped into the court, where I was found guilty and entered my appeal.

Four years later, that was about the only thing AFSC people outside New Hampshire knew about me. Some of them suspected I might not have the proper demeanor to represent the Service Committee.

In my first week on the job, we heard that the U.S. Air Force would be shipping military planes to Saudi Arabia from Pease Air Force Base in Portsmouth, and that Vice President George H. W. Bush was going to drive down from his summer home in Kennebunkport, Maine, to see them off. Since a call for an end to arms sales to the Middle East was on the AFSC agenda, I organized a demonstration at the entrance to the base. When the vice president drove in, we were there with signs that said, “Stop Middle East Arms Sales” and made it into local news coverage. Doubts about my suitability for employment with AFSC began to fade.

Since 1981, Arnie organized hundreds of demonstrations and trained thousands of people in the methods of nonviolent protest. He will retire at the end of June.