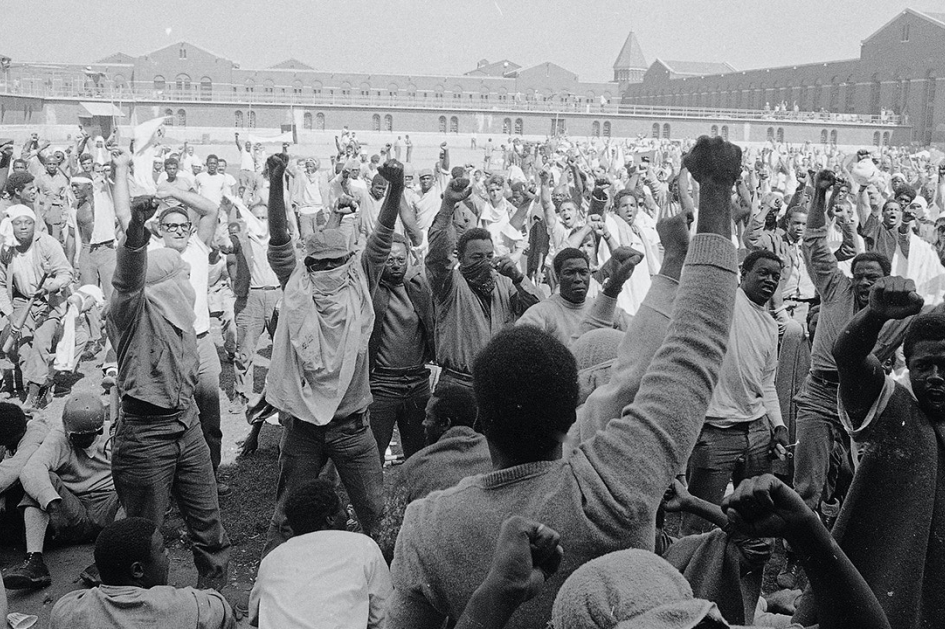

In September 1971, incarcerated people at the Attica Correctional Facility in upstate New York took over the prison, demanding an end to the deplorable conditions that defined prison life. The resulting backlash from the state led to one of the most deadly prison riots in U.S. history.

In popular culture, the legacy of Attica is invoked by a chant (“Attica! Attica!”) to signal that excessive force and brutalization by police is imminent. The uprising ignited a new awareness around prison conditions. Thanks to the work of historians and political educators, we now know more about the unnecessary and extreme violence law enforcement enacted against the people who took part.

During the five-day standoff, 43 were people killed, including 33 prisoners and 10 prison staff. Brutality unleashed on the men of Attica revealed the true face of the U.S. carceral system.

But instead of moving toward abolition, the prison system expanded dramatically in the following years. According to The Sentencing Project, the prison population grew by 700% between 1972 and 2009. The United States is the world leader in incarceration.

Reforms and modest declines in the prison population will not end horrifying conditions for people inside. It is up to the public to not ignore the demands of incarcerated people – in 1972 or today. Their voices and actions should serve as a guide to today’s iteration of the abolitionist movement.

In the 1970s, during the onset of hyper-criminalization and the advent of mass incarceration, prison conditions in the Attica Correctional Facility were abysmal. Severe overcrowding meant 2,200 people resided in quarters meant to fit about 1,600. The men in the prison were locked in their six-by-nine-foot cells for 14 to 16 hours a day and were made to work five hours a day—for about 20 cents to one dollar an hour. They received just one shower a week, and as Attica survivor Frank “Big Black” Smith recollects, “You know, a shower to us in Attica state prison is a bucket of water, and if you lucky and you get the right person outside of your cell that would bring you a second bucket, then you can wash half of your body with one bucket. What we would do is wash the top of our body with one bucket, and if we get a second bucket then we will wash the bottom part of our body.”

Along with physical conditions of imprisonment, racist white guards fomented racial segregation. In response to the cruel treatment endured in prison, Frank Lott, Donald Noble, Carl Jones-EL, Herbert X. Blyden, and Peter Butler created the Attica Liberation Faction. Their main goal was to teach political education to the other members of the Faction, which culminated in the creation of 27 demands written to Commissioner of Corrections Russell Oswald and Gov. Nelson Rockefeller. Rather than meeting their demands, the prison staff retaliated against the organizers.

Shortly after, in August 1971, revolutionary and political prisoner George Jackson was murdered by correctional officers at San Quentin Prison. This sparked protests around the country and mobilized the men in Attica to put aside differences and pay tribute to Jackson’s courage and passion. A hunger strike was called in honor of Jackson just one day after his death. Seven hundred silent prisoners took seats in the mess hall, sporting matching black armbands and refusing to eat. Just a few days later, another protest was held in the sick ward, with people occupying hospital beds to dramatize the inadequate health conditions.

The final straw for the men at Attica was the brutalization of two prisoners after an altercation between them and correctional officers on Sept. 8, 1971. The two men were taken to Housing Block Z (HBZ), an area of the prison where people were routinely assaulted by guards. The next day, the uprising began.

A group of around 20 prisoners overpowered four guards, locking them in cells and taking control of the various cell blocks. Members from the ALF drafted a list of five demands to be met as preconditions for ending the occupation of the prison. The five demands were as follows:

- We want complete amnesty, meaning freedom from all and any physical, mental and legal reprisals.

- We want immediate speedy and safe transportation out of confinement to a non-imperialistic country.

- We demand that the Federal Government intervene, so that we will be under direct Federal Jurisdiction.

- We want the Governor and the Judiciary, namely Constance B. Motley, to guarantee that there will be no reprisals and we want all factions of the media to articulate this.

- We urgently demand immediate negotiations through William M. Kunstler, Attorney at Law, 588 9th Avenue, New York, New York; Assemblyman Arthur O. Eve of Buffalo; the Prisoner Solidarity Committee of New York; Minister Farrakan of the Muslims. We want Huey P. Newton from the Black Panther Party and we want the Chairman of the Young Lords Party. We want Clarence B. Jones of the Amsterdam News. We want Tom Wicker of the New York Times. We want Richard Roth from the Courier Express. We want the Fortune Society; Dave Anderson of the Urban League of Rochester; Brine Eva Barnes; We want Jim Hendling of the Democratic Late Chronicle of Detroit, Michigan. We guarantee the safe passage of all people to and from this institution. We invite all the people to come here and witness this degradation so that they can better know how to bring this degradation to an end. This is what we want.

These five demands were expanded into “15 practical proposals” to be negotiated by various parties including the men inside, representatives for the governor, state prison officials and outside observers. Over the next few days, the demands were heard and dismissed by Gov. Rockefeller. A 28-point plan was negotiated with Commissioner Oswald and rejected by uprising participants. Soon after, Black Panther Bobby Seale arrived, with many close to the situation hoping he could persuade those inside to accept the 28-point agreement. Seale said he would support all decisions made by prisoners and that he would not tell them what they should do. After the rejection of the agreement, Gov. Rockefeller refused to negotiate further, ignoring pleas of desperate hostages.

A day later, on what is known as Bloody Monday, Rockefeller orders thousands of National Guardsmen to swarm the prison. Hundreds of people were shot and killed, including unarmed prisoners and hostages. 39 in total died at the hands of the state and hundreds more were injured, beaten and tortured. All those who died were shot by guardsmen.

By the end of that September, at least 13 other rebellions took place in United States, including three others in New York. While the legacy of Attica symbolizes the inherent cruelty of prison environments, it also cements rebellion as an invariably important part of fighting the conditions of prison life and ultimately in the multiracial struggle being waged against U.S. empire. In early 2021, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, incarcerated folks in St. Louis rose up against unfair sentencing, pretrial detention, and deadly conditions caused by prison officials’ failure to protect them from COVID-19.

Abolitionists take these struggles as evidence of the horrors committed in prisons every day and as fuel to continue struggling for survivors of prisons and those currently incarcerated. In the wake of Attica, we are reminded that many attempts at reform lead to reinforcement of the establishment of the prison. We should let Attica be a reminder of the daily horrors of prison life and why we fight. We must continue to uplift prisoners’ rights and petition for the end of the carceral state.

Citations:

Attica Prison Uprising. Zinn Education Project. (2020, February 20). https://www.zinnedproject.org/materials/attica-prison-uprising/.

Diaz, J. (2021, April 5). Inmates Riot At St. Louis Jail, Setting Fires And Breaking Windows. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/04/05/984337382/inmates-riot-at-st-louis-jail-s... g-windows.

Dotinga, R. (2016, September 14). Examining the legacy of the Attica riots, 45 years later. The Christian Science Monitor. https://www.csmonitor.com/Books/chapter-and-verse/2016/0914/Examining-th... ttica-riots-45-years-later.

Kaba, M. (2011). Attica Prison Uprising 101: A Short Primer. Project NIA. Manos, N. (2017, November 18). Attica Prison Riot (1971). BlackPast.org.

Steel, L. M. (2016, September 26). Understanding the Legacy of the Attica Prison Uprising. The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/understanding-the-legacy-of-th...

About the author

My name is Akira Rose and I am a Black multidisciplinary scholar of the Black Radical Tradition. In May 2020, I graduated from the University of Massachusetts Amherst with a degree in Social Thought and Political Economy. In my time at UMass, I was heavily involved in the Students for Justice in Palestine and the Prison Abolition Collective. I am passionate about issues around police terror, Global South struggles, prison-industrial complex abolition, and anti-capitalism. In my free time I read (currently reading Black Skin, White Masks by Fanon, The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, and Parable of the Talents by Octavia Butler) and I write about the ongoing struggles being waged in the US and beyond. I’m also learning to roller skate and I am teaching myself guitar and drums (it’s harder than it looks!).

My name is Akira Rose and I am a Black multidisciplinary scholar of the Black Radical Tradition. In May 2020, I graduated from the University of Massachusetts Amherst with a degree in Social Thought and Political Economy. In my time at UMass, I was heavily involved in the Students for Justice in Palestine and the Prison Abolition Collective. I am passionate about issues around police terror, Global South struggles, prison-industrial complex abolition, and anti-capitalism. In my free time I read (currently reading Black Skin, White Masks by Fanon, The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, and Parable of the Talents by Octavia Butler) and I write about the ongoing struggles being waged in the US and beyond. I’m also learning to roller skate and I am teaching myself guitar and drums (it’s harder than it looks!).