Q: Please tell us about yourself.

I was born and raised in West Palm Beach, Florida. I went to Kalamazoo, Michigan for college, and there I studied anthropology and sociology, getting my BA. I started doing a lot of work around food justice and food sovereignty, both understanding what it is and also practicing it, particularly in a youth-based context.

I worked at a local elementary school and gardened with students. It was such a formative experience for me, because not only were we growing food together, but we were also cooking it. We talked about why food is important and where food comes from. I don't believe anyone in the program grew their own food.

I also started doing anti surveillance studies. I did my senior thesis on understanding the ties between white Jesus iconography and our contemporary surveillance state. How the idea of a white God as this omnipotent, omniscient figure is very akin to how our contemporary surveillance state works.

When I moved to Chicago in 2021, I found the ShotSpotter campaign. ShotSpotter is an audio surveillance technology that blankets predominantly the south and west sides. It has done a lot of damage to the community. The purpose of the coalition was to get their $9 million contract cancelled and that money reallocated.

Simultaneously I started doing work with Black Youth Project 100, which is a Black, queer feminist organization. It operates nationally but has a chapter in Chicago. Through that I was able to join different initiatives happening around the city to organize around housing justice.

Q: What drew you to AFSC?

I think Chicago is a really organic organizing community. The work that [former AFSC staffer] Debbie Southorn was doing in and around youth empowerment -- I found out about because I was doing work with the Treatment not Trauma coalition.

Debbie had helped organize a youth summit that really centered Chicago youth and made space for youth to talk about mental health in a way that felt generative and relevant.

I started following AFSC on social media, and I was like, “I really want to be a part of this.” All of the work that AFSC was doing on Gaza was coming to me, and I was so inspired to see an organization taking a principled stand on genocide.

I want to help shape what Chicago programming is doing, especially in and around police and prison abolition.

Q: What excites you about working with AFSC?

AFSC’s history. I have never seen an organization that has such a proven track record of taking unpopular stances on things that actually matter. That radical tradition that AFSC carries means so much to me, and I think that it's both the history and the current work that's being done.

The fact that AFSC declared so early, I believe it was in 1978, that they would be an abolitionist organization has given me the freedom to think about the trajectory of abolitionism and where we're going.

I’m also excited to work with Mary Zerkel [Associate Regional Director of AFSC’s Midwest Region]. Mary has been with AFSC for about 30 years and has done so much incredible art-focused activism. Carrying on that lineage and incorporating art in the organizing work we do is very exciting.

I really love art. I particularly love to draw, and I know that art is the calling card of liberation.

Q: What challenges do you envision?

I think we're at a really critical juncture in Chicago around incorporating our local movement work with an international solidarity framework. Local work is really important, but it can be really siloed.

I've been in spaces in Chicago where people are talking about the migrant crisis and how we can provide housing and jobs to our migrant neighbors. But there is not a conversation about how people were being forced to move because of a climate catastrophe that's been aided by the United States and other colonial powers.

There's a lot of tension between our new migrant neighbors and our existing Black community, which has been here for so long but has been abandoned and strategically sabotaged by the city.

There's a lot of resentment there, not necessarily towards the city, but towards our migrant neighbors. That can't happen because we know that these things are interconnected and that there are larger forces pitting people against each other.

How can we as a community come together, recognize our common struggle, recognize that housing and healthcare and education are things that we all deserve and can get? That we ourselves are not the enemy of each other?

Q: If you woke up tomorrow and the problems of state and police violence were solved the way you want them to be solved, how would you know that? What would that world look like?

I would know by looking around my neighborhood and seeing no gates on things and no big box stores, but actual community plots where people are growing food intergenerationally. Children, elders and parents are all there. Nobody is enroute to a nine-to-five job. People are laughing, talking, dancing and being together.

I would know by seeing no tents at the end of my block where people have to live because they can't afford housing. People would just be housed. It wouldn't look like the gentrifier gray buildings that we have, but there would be buildings with different colors materials.

I would know because I wouldn’t hear police sirens all the time, like I do every day. It would be just the relief of knowing that state violence is no longer with us. Both visually and somatically, we can feel state repression.

I'd also see more bike lanes and fewer cars -- more accessible infrastructure for people of all abilities. Living life in my community without restriction. That's how I would know.

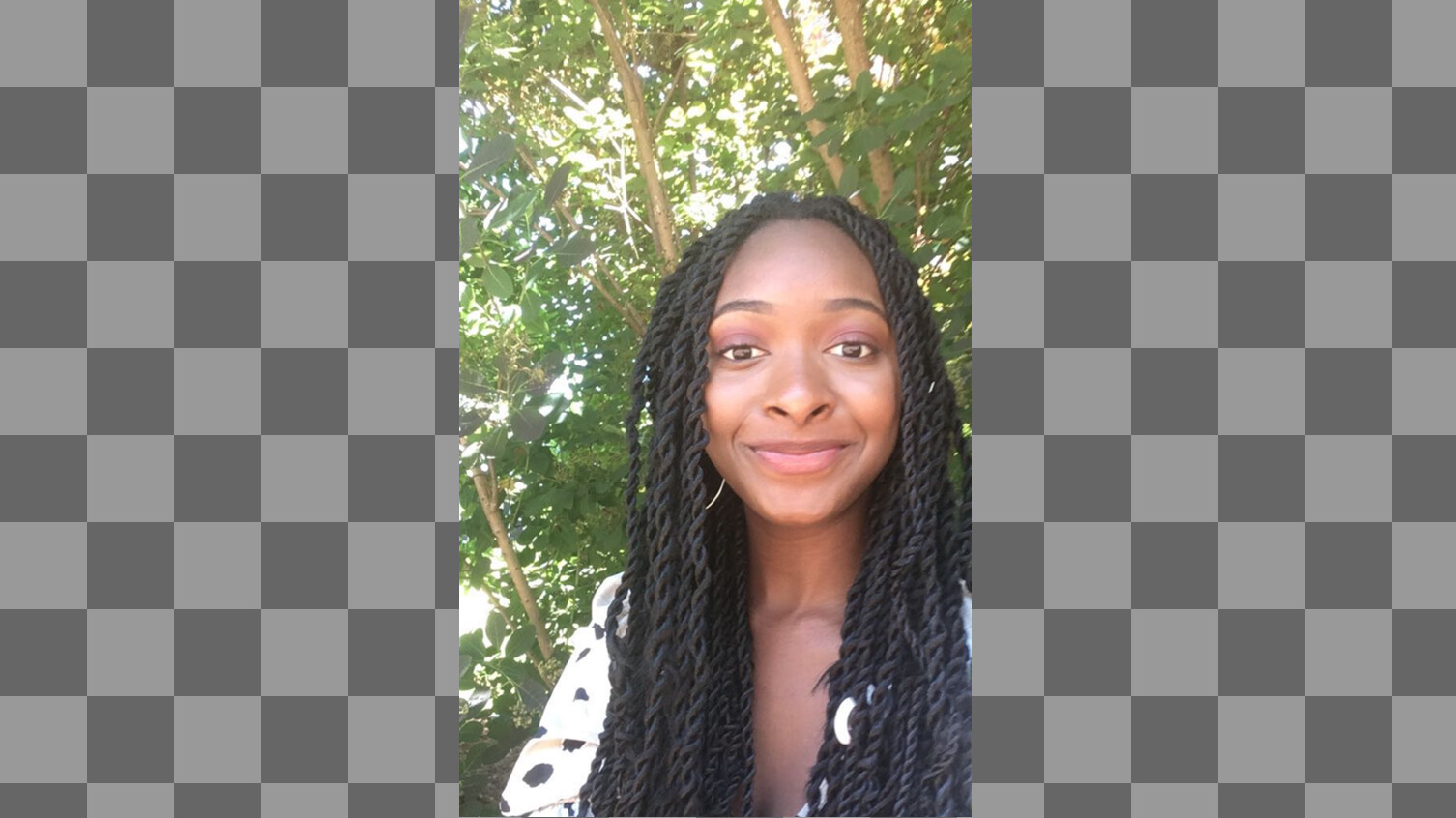

Mary Zerkel, left, and asia smith protest outside a UPS store in Chicago to Stop Cop City.