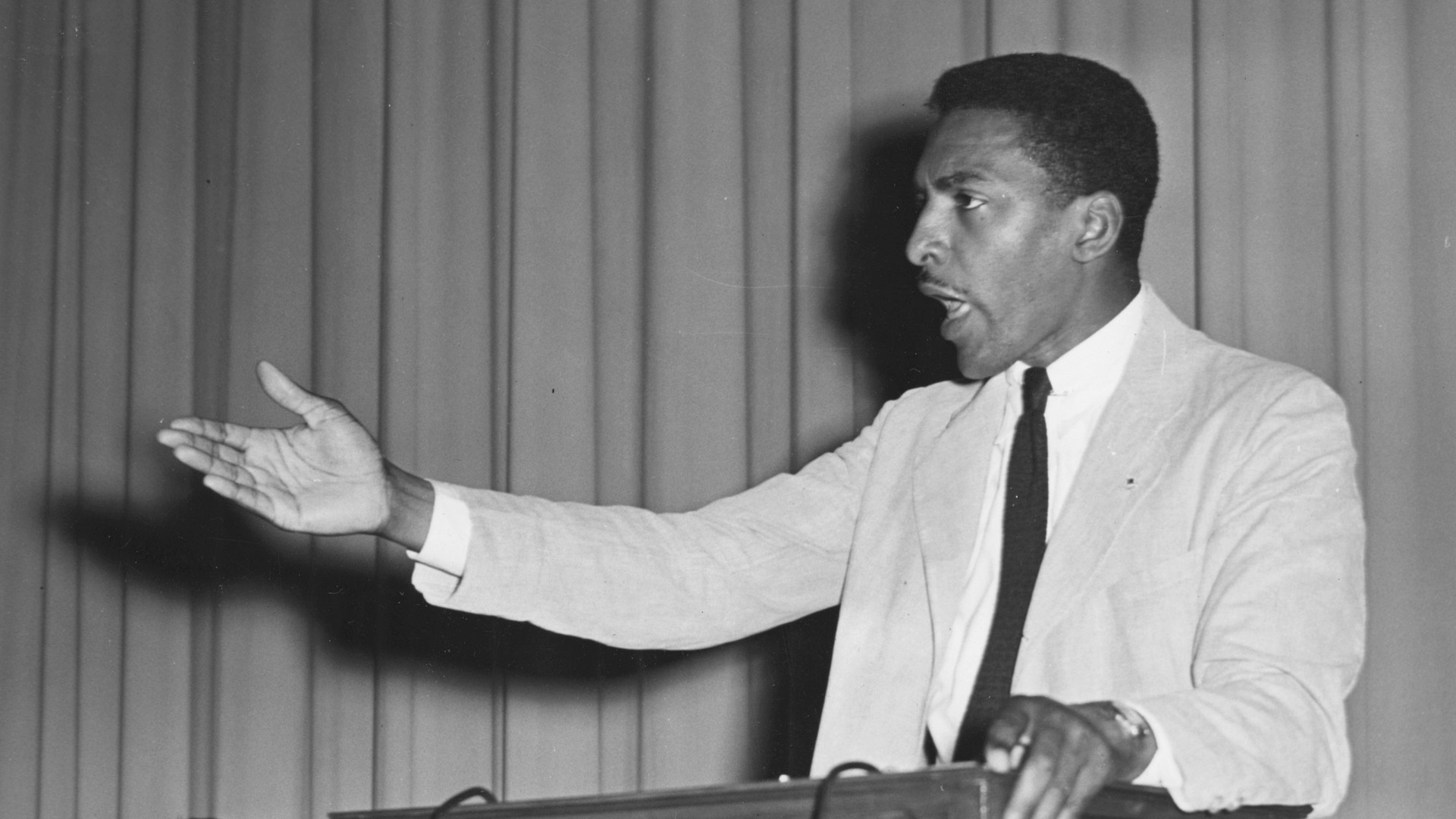

Listen to a clip of Bayard Rustin speaking at the 1965 Madison Square Garden rally against the war in Vietnam. Photo: Harry H. Haworth

The summer of 1963 was a tense and brutal time in the deep South. Protests against racial segregation were widespread, and NAACP leader Medgar Evers was assassinated in Jackson, Mississippi.

A serious and religious teenager in suburban New Jersey, I was intrigued by the nonviolent African-American struggle and sickened by images of people—some my own age—being arrested, beaten, and even killed merely for exercising their right to peaceful protest. A week before I started high school, an event occurred that restored—at least momentarily—the hope that our nation could overcome its racial divisions.

That event was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and it was the first time I’d heard the name Bayard Rustin, who was instrumental in organizing this historic event. I couldn’t know that 14 years later, Bayard and I would become life partners, sharing much happiness rooted in the values of our early religious training.

As the Aug. 28 march approached, I remember seeing Bayard appear frequently in the press—handsome, harried, and articulate. He was usually identified as the “genius” behind the march, but he was also attacked publicly by such figures as Sen. Strom Thurmond and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover.

Although an important leader in the movement for civil rights and peace, he was often marginalized because he was a gay man, unashamed and open at a time when same-sex relations were criminalized and classified as a psychological disorder.

A young organizer influenced by Friends and AFSC, Bayard’s unwavering commitment to nonviolence and equality can be traced to his childhood in West Chester, Pennsylvania, where he was raised by his grandparents. He was profoundly influenced by the values and activism of his grandmother, Julia Davis Rustin, who had attended a Quaker school and whose mother was employed by a Quaker family. Bayard’s own journey as a nonviolent activist began as a high school student, organizing local protests against segregation.

Bayard became involved with AFSC in 1937, when he took part in an AFSC-sponsored activist training at Cheyney State Teachers College. The training broadened his worldview as participants from around the country discussed economics and class—in addition to racial or ethnic differences—as roots of conflict. That summer, he served as an AFSC “peace volunteer” in central New York, spending his days working with farmers, and his evenings and weekends speaking on behalf of peace. In 1941, he was the sole Black member of an AFSC delegation investigating the plight of conscientious objectors in Puerto Rico.

Working with the Fellowship of Reconciliation and AFSC in the 1940s, Bayard traveled around the country to address racism, colonialism, and conflict, joining campaigns to protest the internment of Japanese Americans and support India’s struggle against British rule. As a conscientious objector, he spent two years in prison for refusing cooperation with the Selective Service Act. Soon after his release, he returned to the road, sharing accounts of his prison experiences and addressing the new threat of atomic annihilation.

In 1954, as the Cold War escalated, Bayard was among a group of men who authored AFSC’s influential document “Speak Truth to Power,” which called for nonviolent alternatives to end the crisis. Although Bayard was an important member of the group, he asked that his name be omitted from the publication, fearing that his recent arrest on a morals charge would be used to discredit the document and its message. It wasn’t until 2012—the year that Bayard would have turned 100—that AFSC restored his name to the publication, issuing an apology for its original omission.

Nonviolence in the struggle for civil rights

Bayard Rustin became involved with AFSC in 1937, when he took part in an AFSC-sponsored activist training at Cheyney State Teachers College. Photo: Harry H. Haworth

In 2013, on the centennial anniversary of the March on Washington, numerous articles lauded Bayard as a key strategist in the Civil Rights Movement while acknowledging how he had been “kept in the background” because of his sexual orientation and his radical beliefs.

But in his decades of activism, Bayard was a powerful voice for equality that moved audiences. He often led them in local protests and deliberately courted arrest through nonviolent direct action. In 1947, for instance, he helped organize the “first Freedom Ride”—challenging segregation on interstate buses over a decade before the term was ever used—and served 22 days on a North Carolina chain gang.

“We need in every community a group of angelic troublemakers!” he once said. “The only weapon we have is our bodies, and we need to tuck them in places so that wheels don’t turn.”

In 1956, Bayard traveled to Alabama to work with organizers of the nascent Montgomery Bus Boycott. His experience mounting nonviolent protests made him a close and influential adviser to the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. He also served as a liaison between the movement’s leadership and the Quaker community, arranging Dr. King’s first meetings with Friends.

Following the successful civil rights legislation of the ’60s, Bayard devoted more attention to issues that he had worked on in the 1940s: human rights and economic justice for all people.

His activism would remain inextricably linked to his Quaker values and upbringing. Speaking at a rally for gay rights not long before his death, Bayard said, “We are all one, and if we don’t know it we will learn it the hard way.”

Walter Naegle was Bayard Rustin’s partner and co-author of “Bayard Rustin, The Invisible Activist.”