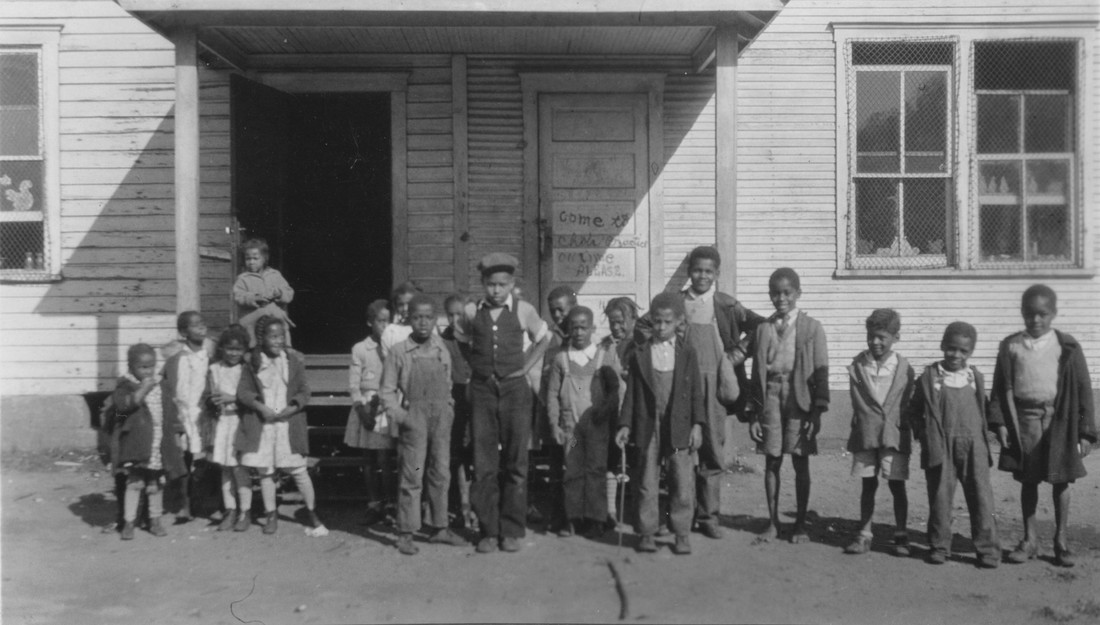

AFSC helped provide children with food in the 1930s. AFSC Archives

IT WAS 1922 IN WEST VIRGINIA. Coal mining was the state’s leading industry. Jobs peaked during World War I but collapsed in its aftermath, leaving many families stranded and suffering. Even in “good” times, West Virginians saw little of the profits reaped by companies. Workers labored in dangerous conditions—risking health and lives—and paid a pittance for each ton of coal. Many lived in crowded, unsanitary company-owned coal camps and struggled to put food on the table.When coal operators cut pay and resisted unionization, miners would strike, with mixed results. Employers used hunger, evictions, intimidation by armed mine guards, and the power of the state to keep miners down. In 1921, the “mine wars” culminated in “the Battle of Blair Mountain,” the largest workers’ uprising in U.S. history. It wasn’t until the New Deal of the 1930s that miners would secure organizing rights.

That’s when Quakers and AFSC stepped in. We had fed children in Europe during and after World War I. Here, we started with a program to provide food for around 400 children. When the Great Depression hit, thousands more miners faced unemployment. In 1931, President Herbert Hoover asked AFSC to expand our program. Soon, we were helping feed more than 22,000 children a day, while also influencing federal relief policies and improving access to shelter, sanitation, and health care.

Relief was only part of the equation. Communities needed alternatives to coal mining. In 1932, AFSC helped establish the Mountaineer’s Craftsmen Cooperative Association to support people in transitioning to furniture making and other trades.

Craftsman Bob Godlove trained miners in furniture making techniques. The community established a workshop. And AFSC staffer Edith Maul logged more than 100,000 miles driving truckloads full of furniture through Pennsylvania and West Virginia to find buyers. It was one of several efforts to develop alternative sources of income.

In the 1970s, AFSC’s New Employment for Women (NEW) program offered the first classes to train women for work in the mines. Later, NEW became a community resource for African Americans, women, and low-income people in the coalfields.

This year marks 100 years of AFSC working in solidarity with West Virginians for a better future. As we commemorate this anniversary, we look at how this history informs our work today.

Protesting police violence on Racial Harmony, Action and Peace Day in 1991. Photo: Terry Foss

Standing in solidarity with workers

Rick Wilson, director of AFSC’s West Virginia Economic Justice Project (WVEJP) since 1989, said “A lot of our work has been in solidarity with people working in, living with, or harmed by extractive industries,” he says. “We try to influence laws and policies to ensure they serve the interests of working-class and low-income people.”

In 1989, miners working for Pittston Coal went on strike to preserve benefits for retirees and their families. AFSC staff walked picket lines, provided media support, and arranged speaking venues for miners and their families. We provided families with clothing and other material aid, assisted a support group for miners’ spouses, and led a Christmas toy drive for the children. Eventually, the union won a settlement, helping many retirees and their survivors over the years.

In 2010, AFSC played a key role in calling for corporate accountability after 29 miners were killed at the Upper Big Branch coal mine. The mine was owned by Massey Energy, which had a long history of safety issues. WVEJP coordinator Beth Spence served as lead writer on an independent panel established by then-Gov. Joe Manchin to investigate. They found the explosion was the result of Massey’s failure to maintain basic safety procedures. The report drew national media coverage and fueled advocacy for mine safety. In 2015, the company’s former CEO was convicted of conspiring to evade federal safety standards, a first in U.S. history.

“You shouldn’t need to rely on luck or wealth to maintain your family’s stability or the dignity of your own work.” —JOANNA VANCE, AFSC FELLOW

Strengthening the social safety net

Advocacy with people in poverty is still key to our work in West Virginia. “Not many organizations work with impacted people to organize like AFSC does,” says JoAnna Vance, who joined AFSC’s West Virginia program as a fellow in 2021.

“There’s still such a need to address hunger and malnutrition in the state,” adds Lida Shepherd, youth and economic justice program director. “But we have gained some ground.”

West Virginia mothers demonstrating in Washington D.C in support of the Child Tax Credit in January 2022. Photo: Mark Story Photos

Creating a prosperous future

West Virginians are making a painful economic transition—and working toward a more just, prosperous, sustainable future for all.

One priority is ending mass incarceration. We support efforts to reform bail and probation, promote reentry, reduce the prison population, and more. “People in West Virginia and around the U.S. are reflecting deeply on the real costs of incarceration—in terms of taxpayer dollars, the loss in human potential, and the trauma on children and families,” Lida says. “We must create a system that is safe, just, and more beneficial to individuals and society.”

We also support organizing and advocacy efforts by young people. Since 2012, around 450 young people have participated in the activities of our youth leadership program, the Appalachian Center for Equality. Headed by Youth Director Liz Brunello, the center helps participants develop skills and lead campaigns to demand policy change. And we are still working tirelessly for economic justice.

“Whether you work in the field picking vegetables, in a plant packing meat, in a mine digging coal, or in a city typing at a desk, you shouldn’t need to rely on luck or wealth to maintain your family’s stability or the dignity of your own work,” JoAnna says.

Rick says, “Decisions about distribution of resources are made at different levels. Our history has shown that it’s possible to influence many of them—and sometimes make progress even in tough situations.”