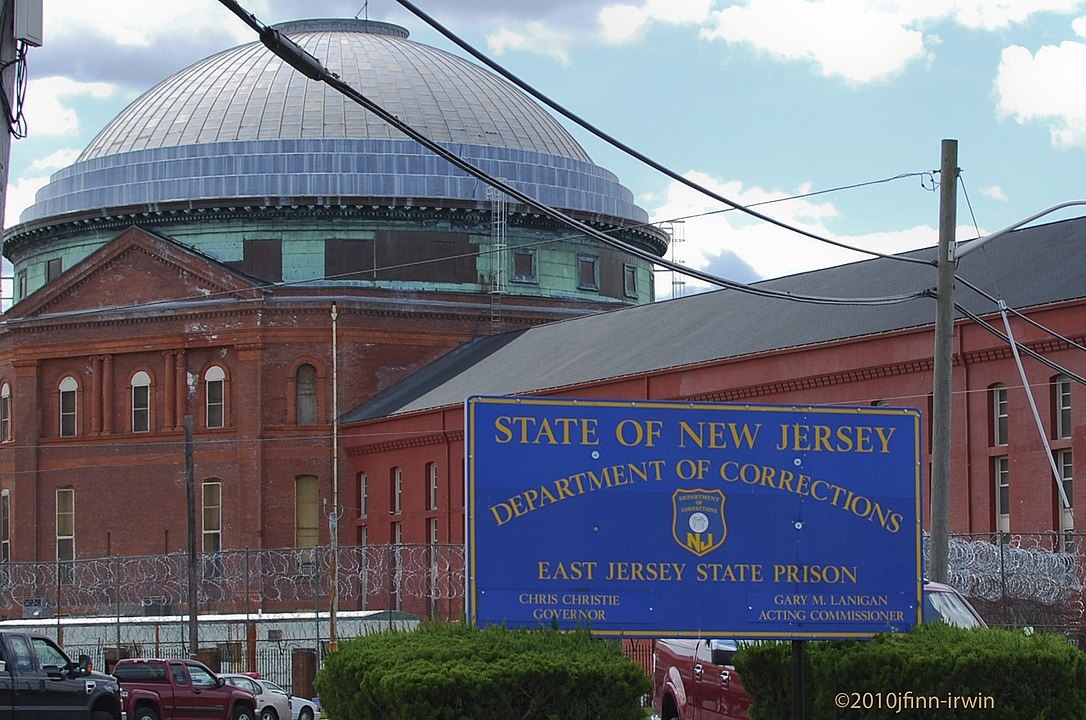

An estimated 1,700 people are imprisoned for technical parole violations in New Jersey. Photo: Jackie Finn-Irwin via Flickr CC

After serving over eight years in prison, D.W.* was working hard to rebuild his life. He was a full-time college student at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey. But when he moved out of his dorm into a family member’s home at the end of his fall semester, he forgot to immediately notify his parole officer.

Two days after the move, D.W. was summoned by his parole officer and told that he had committed a technical parole violation. For this minor infraction, he was condemned to another 30 months in prison. That's two-and-a-half years simply for failing to report a change of address in the same city.

D.W. is just one of the estimated 1,700 people imprisoned in New Jersey for technical parole violations. They have not committed or been convicted of new criminal offenses. Technical parole violations are usually minor infractions such as missing an appointment with a parole officer, missing curfew, failing a drug test, or not being able to pay fees. Still, these infractions can lead to reincarceration, once again tearing people away from their loved ones and communities.

An irrational, inhumane system

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, the parole system is supposed to support people in finding employment, housing, and managing personal issues to help them adjust to life after release. It is also supposed to reduce recidivism by integrating people back into the community. And it should prevent unnecessary imprisonment.

But today, our current parole system in New Jersey—and in many places across the U.S.—fails to do that. Instead, it dehumanizes individuals, does nothing to make our communities safer, and wastes millions of tax dollars.

When a person is released, they are subject to strict conditions of supervision. Far too often, these conditions can become stumbling blocks with harsh consequences.

AFSC staff have heard from multiple people in New Jersey who have been reincarcerated for technical parole violations. That includes M.M., who served over 11 years in prison. He was sent back two days after his release because a state of emergency declared by the governor prevented him from immediately reporting to his parole officer. Although he contacted his parole officer, he was put behind bars for 90 days because there was no written documentation of their conversation.

The process of sending someone back to prison is also subject to abuse and biases of individual parole officers. That was clear in the case of IC. During a routine visit, I.C.’s parole officer demanded to speak with him in his private bedroom. But I.C. questioned this request and cited his rights. The officer later returned with backup, which escalated the situation. They charged him with a technical parole violation for refusing a search, despite this being untrue.

Parole officers also create challenges by making inflexible demands that interfere with someone’s work schedule or personal life. We have heard accounts of people being asked to report to meetings with parole officers in the middle of their own workdays. We have also heard accounts of

officers showing up at someone’s workplace unannounced, making it uncomfortable for them around colleagues.

One formerly incarcerated person shared that his parole officer had barged into his home at 7 a.m., waking up his family members. When he requested that the officer visit after a certain hour in the morning so that his mother and sister would have enough time to leave the house, the officer blatantly ignored his request. Upon receiving a complaint, the officer threatened to send him back to prison.

The need for change

Sending people back to prison for technical violations is counterproductive and cruel. People on parole need resources, not confinement. They should receive help with housing, mental health services, and job opportunities. To break the cycle of reincarceration and homelessness, we need to divest from imprisonment and invest in more support programs.

The current cycle of reentry and release for parolees wastes taxpayer dollars—and costs much more than helping people through support services. The estimated cost of incarcerating someone in New Jersey is $75,000 per year. Providing community support costs around $6,000 annually.

People who have served their time should be given a fair chance to reintegrate and contribute to society. But the current parole system robs them of that opportunity. It dehumanizes people and subjects them to further stigma and discrimination. It makes it harder for people to rebuild their lives after release. And it creates a revolving door between prisons and communities.

A path forward

AFSC’s Prison Watch Program is part of a coalition working to transform the system of parole in New Jersey. We want the state of New Jersey to reconsider the costly and irrational practice of reincarcerating individuals who have already met the onerous standards for parole.

For AFSC, keeping people out of prisons is part of our long-term work toward a future without incarceration. Earlier this year, we published a report that examined the impacts of technical parole violations on individuals, our communities, and our state. The report draws from real-life testimonies of people incarcerated for minor infractions.

Our report includes recommendations to change the conditions of parole from surveillance to partnership—and to emphasize the humanity of people released. We urge New Jersey to:

- Abolish the practice of reincarcerating people for technical violations.

- Allow people on parole to remain free while awaiting revocation hearings.

- Divest funds from reincarceration to direct aid and support programs.

- Implement grants to support reintegration.

- Ensure the distribution of necessary documents and resources for people on parole.

- Transform parole officers into partners rather than supervisors to aid in freedom maintenance strategies.

It’s long past time that we create a new parole system that focuses on support, instead of punishment. This new approach could involve retraining parole officers to better recognize trauma and provide care. It would also require moving funds from imprisonment to programs that promote health, well-being, and reintegration after release.

As a society, it's time to stop locking people up simply because we failed to provide them with adequate support. Instead, we must ensure that everyone has a fair chance at rebuilding their lives.

*Initials are used to protect people’s identities.