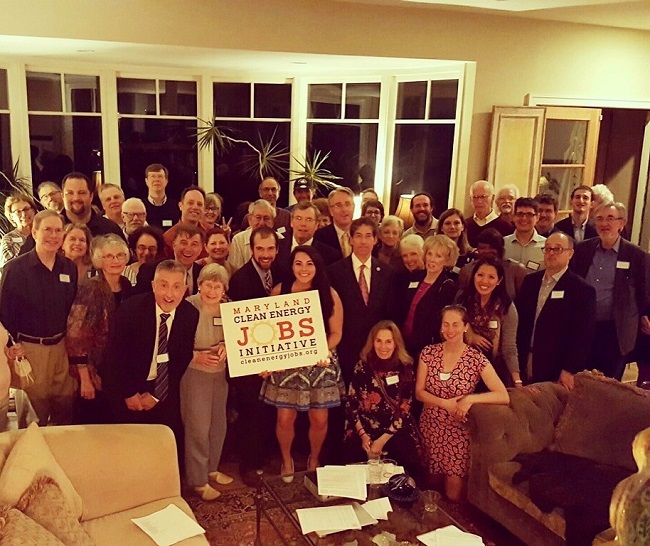

Nikki Richards was born in Silver Spring, Maryland and grew up in Baltimore. Before working with AFSC, she co-founded a nonprofit called the Maryland Clean Energy Jobs Initiative where she managed a campaign to increase renewable electricity and clean energy jobs in the state of Maryland. While working to pass the Clean Energy Jobs Act, Nikki served as lead fundraiser and planned dozens of fundraising events to support the campaign. The law passed in April 2019.

Nikki attended Sandy Spring Friends School for 12 years and worked for nine years as a counselor and then assistant director at the Baltimore Yearly Meeting Quaker camps Shiloh and Teen Adventure. Following her time at Sandy Spring, she continued to Swarthmore College and currently serves on the Baltimore Yearly Meeting STRIDE Committee (Strengthen Transformative Relationships In Diverse Environments), which helps to remove barriers and create access to the Quaker camps for youth in Baltimore. She is excited to combine her fundraising skills with her Quaker roots and values to ensure that AFSC can continue to promote peace and lasting justice as an expression of faith in action.

Sophia: What work do you do for social change?

Nikki: Within AFSC, I am a leadership and planned gift officer, so my job is to fundraise. Most of what I do involves meeting with donors. We go around the country in our territories and meet with donors to establish connections with them and develop relationships. That’s for several reasons, but I think the one that feels most in line with AFSC’s values is the idea of convening. We’re helping to connect the people who are supporting this work – and who have been supporting this work for years and years -- with the work that’s happening by meeting with them, talking to them about AFSC, finding other ways for them to get involved if they want to. That is one of the ways that AFSC tries to convene people from all walks of life by having leadership gift officers going and meeting with the donors around the country.

Before AFSC, I was working on a clean energy and jobs bill for the past two years. My friend and I started a nonprofit to try to pass a law to increase clean energy in Maryland to 50 percent by the year 2030, while also investing in clean energy jobs via training programs, like teaching people how to install solar panels on roofs and also investing in clean energy businesses owned by women and people of color. One of the reasons I felt strongly about that bill is that it wasn’t just the environmental component, it was also a jobs component, which I think is very important because as you grow the clean energy industry, you’re also growing the economy and making opportunities for people to be part of that industry. That was social justice work, too, and the law actually passed a few weeks ago!

Sophia: What does being a Quaker mean to you?

Nikki: For me, I knew that I was home. I wasn’t raised Quaker, but I went to Sandy Spring Friends School from the age of six to the age of 18 and went to several Quaker colleges, as well. Around my freshman year of high school, I decided I wanted to be Quaker because it felt right. I went to the Baltimore Yearly Meeting summer camps and absolutely loved them. That was where I first fully felt accepted and felt at home. Then I started going to Quaker meeting on Sundays, and I had been going to Quaker meeting at school twice a week during the school day for years, but after camp and going to meeting on Sunday, I really felt this was just where I was supposed to be.

One of the reasons I strongly identify with Quakerism is the testimony of integrity, which also for me means honesty. A big part of Quakerism involves trying to find the spirit within you and within others, sort of searching for the truth. You have to be honest with yourself about whether or not you’re actually on that path of finding the truth. For me it’s a very personal thing, and I don’t have to abide by anyone else’s guidelines for the journey. For me being a Quaker is about being honest with myself about whether I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing, whether I’m in the direction I’m supposed to be in, whether I’m interacting with other people the way I should be. Nobody else can know if I am or not. For me, I need to be honest with myself about if I am doing what I’m supposed to be doing. Quakerism allows and pushes me to do that.

Sophia: How does your social change work and Quaker faith work connect?

Nikki: They are very connected, and it goes back to the concept of integrity again. How should I treat other people? And what do other people deserve on this earth? Obviously respect and human rights [are at the core of that]. Social justice work is a very clear honest answer to the question, "Am I treating other people the way I should be treating them, and am I doing what I’m supposed to be doing?" Part of what I’m supposed to do on this earth is help other people and to learn from other people.

My spirituality and my faith calls me to do social justice work because how could I do anything else? It’s just very clear to me within the testimonies, all of them are in line with treating other people with respect and dignity. Basic human rights are rights.

Oftentimes, Quakers are not as progressive as we would like to be or think that we are. It calls in the testimony of integrity, and we as a Quaker community need to be honest with ourselves, are we really doing what we’re supposed to be doing right now? I want to hold other Quakers’ humanity, too, and know that oftentimes in Quakerism we’re told when we’re young that Quakers do the right thing all the time. So it’s hard un-believe that or un-learn that.

Sophia: What is your vision for a just world?

Nikki: My vision of a just world is one in which everyone has access to the basic rights that they deserve. So much of what makes our world unjust has to do with racial inequality. And wealth inequality plays a part, too, though racism is the driving force behind all that we are fighting against here at AFSC. In a just world, we wouldn’t have billionaires who hoard money and resources and we would have racially driven equity for people – this means reparations need to be paid. People would have access to the things that they need to survive and racism would not skew and hinder that access. In this vision of a just world, folks could actually thrive. Greg Corbin, the director of the Philadelphia Social Justice Leadership Institute program, describes our world as spiritually unwell. In my vision of a just world, that is no longer the case. Our world would be spiritually well. Redistributing resources, including at an institutional level, to people who have been historically shut out will help us get there.