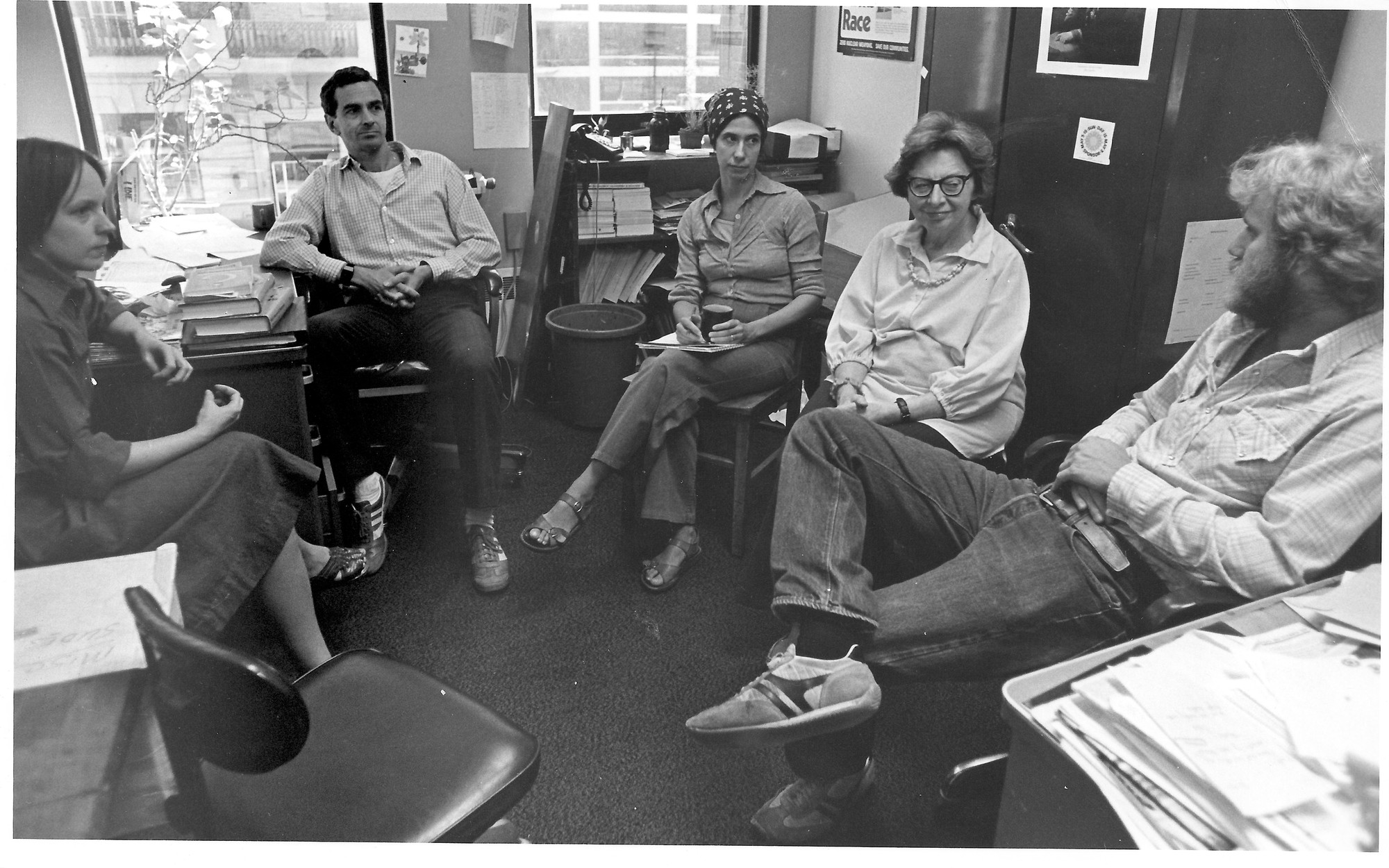

Meeting in the early days of NARMIC. Pictured, from left: Diana Roose, John Lamperti, Eva Gold, Gladys Taylor, and David Goodman. Photo: AFSC Archives / AFSC

We sometimes fail to recognize injustice when it is imposed through systems that benefit us. But when facts and stories reveal those injustices and we see their consequences in human terms, the truth opens the way to action.

Warfare became less visible during the course of the Vietnam War as the U.S. developed technologies that moved battle from ground combat to air attacks. Fewer American casualties and fewer troops on the ground meant stories of war’s atrocities were muted back on U.S. soil.

But in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, new chemical and biological weapons left millions maimed and suffering.

The U.S. had spent $3 billion developing its automated air war systems before Congress or the public learned of it in 1969. Worried about the deepening hold of the military-industrial complex on American society, AFSC and antiwar activists across the country felt compelled to expose the role of U.S. corporations in the air war.

It was in this atmosphere that Fay “Honey” Knopp (1918–1995) and AFSC peace education secretary Stewart Meacham (1911–1985) approached AFSC’s leadership about creating a research collective that would publish materials for public education on the power of U.S. militarism.

They called it the National Action/Research on the Military Industrial Complex—NARMIC. The idea of “action/research” was to uncover and publish facts for the purpose of action. Their goal was to research companies profiting from the Vietnam War and publish material that antiwar activists could use to put pressure on various aspects of U.S. society.

AFSC assembled a team of recent college graduates—a few from Quaker backgrounds, and many who were graduates of Earlham College. “They were all frenetic and worked long hours,” remembers Bob Eaton, a draft resister on the AFSC Board of Directors at the time.

From the start, the NARMIC researchers drew inspiration from Quaker abolitionist John Woolman and his relentless reminders to see and take responsibility for injustice imposed through economic systems.

“The phrase ‘moral imagination’ was used a lot,” Bob recounted in 1989. He remembered NARMIC’s reverence for Woolman’s capacity to explain “not just the moral indignation against the concept of slavery, but how it worked as an economic system which benefited some and oppressed others.”

Tracing the chain of destruction from U.S. war profiteers to mutilations and killing in Southeast Asia using pamphlets, slide shows, and action guides, NARMIC emphasized the inhumanity of profiting off of violence and empowered U.S. communities to stop it.

Researching defense contractors, the group started its work in 1969 by identifying manufacturers of weapons being used in the war and mapping out their connections with each other.

To get this unclassified but sheltered information, AFSC purchased access to a service designed to match companies with Pentagon contracts. It was cost-prohibitive for community activists to purchase individually, but a good investment for a national organization with a wide network.

“People would call us, and say, ‘We have this plant in our town, and we’re trying to figure out what they’re producing there, and if it’s related to the war,’” recounts Diana Roose, who joined NARMIC in 1971 after graduating from Swarthmore College, where she was a draft counselor. NARMIC shared information from their files with such callers and provided research services to campaigns focused on manufacturers like Honeywell, General Electric, and ITT.

Publications like the handbook “Weapons for Counterinsurgency” and the Washington Monthly article “You Can’t Keep a Deadly Weapon Down” put NARMIC on the map as a source for information on chemical and biological weapons.

With these materials, people in New England came to know that their communities played a large part in developing and profiting from the expanded technology of warfare. The Department of Defense met in Wellesley, Mass., air weapons were maintained in Bedford, Mass., and banks were funding new technologies throughout the region. These activities were shrouded in mystery until NARMIC exposed their connections to the war. AFSC's Cambridge office then helped people confront war industries and raised questions about how technology can serve people best.

The Minneapolis peace group known as the Honeywell Project also drew on NARMIC materials to protest Honeywell, Inc.’s production of deadly anti-personnel fragmentation bombs that were used to kill civilians, including children and farmers.

In 1972, NARMIC produced a slideshow called “Automated Air War” that became one of the main organizing tools for many parts of the antiwar movement. Running about 30 minutes, the script and slides were a portable tool for engaging people emotionally and intellectually. Groups could purchase a copy for $50 and project it anywhere—including bars and parks—where people gathered.

“It was very educational and somewhat provocative,” says Diana, referring to how the slideshow juxtaposed facts about weapon production with photos of weapons in use on farmers, kids, and wildlife. “It was the first time a group had put together a slideshow about this new kind of war.”

All told, long before the power of Google, NARMIC researched over 50,000 documents and identified the top 100 defense contractors in the U.S. The founding members set the stage for two decades of AFSC supplying information for activists—including support for the efforts to change U.S. policy in Central America and the anti-nuclear movement. Their work to publish the truth continues to inspire peace educators.

Stewart Meacham made a clear case for AFSC’s emphasis on action/research: He wrote that once the worst horrors and injustices have been built into a system, becoming part of the normal state of affairs, “it can be overcome only if the truth is boldly published and acted upon.”

Today, AFSC's Action Center for Corporate Accountability carries on NARMIC's legacy. ACCA aims to expose, isolate, and reduce corporate complicity in state violence. It focuses on corporations involved in mass incarceration, immigrant detention, border militarization, and the Israeli military occupation and apartheid system.