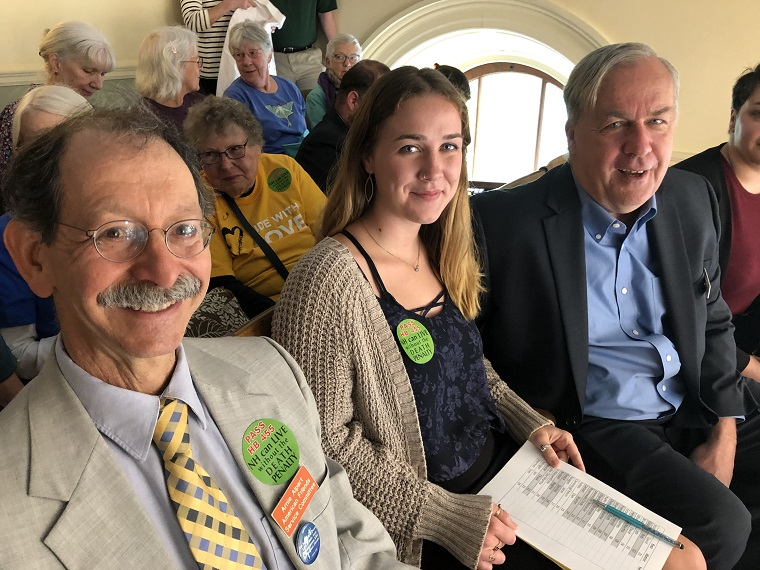

AFSC Arnie Alpert, Grace Cushing (daughter of Rep. Renny Cushing), Rep. Renny Cushing, (far right) daughter Elizabeth Cushing. The picture was taken before the Senate voted on May 30 to override Gov. Sununu’s veto of the death penalty repeal bill. Photo: Paula Tracy/InDepthNH.org

When New Hampshire’s new attorney general announced his desire to change the state’s method of execution from hanging to lethal injection, New Hampshire Quakers said they were appalled at the notion. When the state deliberately kills a human being, they said in a letter to Governor John H. Sununu, “it tends to foster a general disrespect for life and sets a poor example for others who may be tempted to kill or inflict harm for revenge or punishment.”

The letter, approved at a gathering of New Hampshire Friends and signed by Marian Baker as presiding clerk, encouraged legislators to reject the AG’s proposal and instead suggested that “executions should be eliminated as an available form of punishment.”

The year was 1985.

It took 34 years for the Quaker suggestion to abolish the death penalty to become reality.

On Thursday, the New Hampshire Senate followed the state House in overriding our current governor’s veto of a bill to repeal the death penalty. And I am filled with gratitude as I think of all the people whose actions, prayers, testimony, and persistence made the difference.

Death penalty abolition has been on the agenda of AFSC’s New Hampshire Program since the adoption of the 1985 minute and the day I accompanied Marian Baker to deliver it at a State House public hearing. But it was not until 1998 that an organized repeal campaign began.

Oddly enough, it was a series of murders in 1997 that launched it. The killings of three police officers, the rape and murder of a six-year-old girl, and the murder of a judge and a journalist -- all within a two-month period -- created political conditions that made death penalty expansion politically popular, regardless of the fact that those killings were largely covered already by the state’s capital murder statute. When the 1998 legislative session opened, Republican leaders of the state House and Senate teamed up with Democratic Gov. Jeanne Shaheen to introduce a bill greatly expanding the list of crimes punishable by execution. Passage appeared likely.

With leadership from the NH Council of Churches, participation from Concord’s rabbi, the local ACLU, AFSC, several Quakers, and a few legislators, we organized against the expansion proposal. On the day of the vote, two of our legislative allies decided that instead of simply arguing against expansion, they would call for the death penalty to be abolished altogether.

Rep. Clifton Below, then 42 years old but already a veteran legislator, was the son of a Protestant minister and brought a preacher’s touch to his speech on the House floor. “When possible,” he said, “we should choose life over death, good over evil, the possibility of redemption over destruction, of healing over revenge, love over hate.” Speaking about the potential of every human being -- even those who have committed brutal violence -- to repent and gain redemption, Below lifted up the example of John Newton, a slave ship captain who was responsible for the death of scores of men, women, and children. Seeking redemption from such evil, Newton became an activist in the movement to abolish the slave trade and wrote the great hymn “Amazing Grace.”

“Who are we to deny the possibility of redemption, true change, and healing?” Below asked.

Rep. Renny Cushing followed, addressing the 350 House members from his perspective as the son of a homicide victim. Ten years earlier, he recalled, his father was watching the Celtics on TV when he answered a knock at the front door. “Two shotgun blasts were fired through the screen, lifting him up and hurling him backwards, the shrapnel lifting the life out of him before my mother’s eyes.”

“The most difficult thing I have ever had to ask anyone was for help in getting my father’s blood cleaned off the floor and walls,” he explained.

With his infant daughter, Grace, in her mother’s lap in the House Gallery, Cushing told a rapt audience of lawmakers, “If we let those who murder turn us to murder, it gives over more power to those who do evil. We become what we say we abhor. I do not want the state of New Hampshire to do to the man who murdered my father what that man did to my family.”

The repeal measure failed that day, but so did expansion. For death penalty opponents, it was a moment of awakening to the fact that abolition was possible, that moral arguments had weight, and that the stories of murder victim family members who rejected retribution could be transformative.

Over the decades, dozens of people, including Quakers, who have lost their loved ones to violence have told their stories. Margaret Hawthorn described the day in which her daughter Molly was killed by an intruder in her Henniker, New Hampshire home, and how Margaret had proclaimed at Molly’s memorial service, “We will not succumb to fear, nor will we give in to any desire for revenge.”

Bess Klassen-Landis told legislators about the brutal murder of her mom by someone who was never caught. “The last thing my mother would have wanted would be for an act of violence to be committed in her name,” she came to realize. Year after year, at public hearings and in private conversations, such stories have helped legislators feel OK letting go of a social need for revenge.

Their stories were supplemented by the accounts of people like Kirk Bloodsworth and Sabrina Butler -- wrongfully accused, tried, found guilty, and sent to death row for crimes they did not commit. Having been exonerated, they now dedicate their lives to explaining that a legal system run by fallible human beings cannot be allowed to determine who deserves to live and who to die. Stories, too, from former judges, police, corrections officers, and prosecutors have helped legislators understand that execution makes no contribution to public safety.

This morning, I sat in the Senate gallery with Grace Cushing, a recent college graduate, while the votes were counted. Her father, still a legislator, has been campaigning for abolition non-stop since the day he and Rep. Below addressed the NH House in 1998. Step by step, week by week, bill by bill, year by year, heart by heart, and head by head, the stories have added up to where we are today, with two-thirds of representatives and two-thirds of senators -- members of both major political parties -- able to cast votes for repeal and leave the death penalty behind us.

“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said at the end of the march from Selma to Montgomery. Today, I feel like I’m at the end of a march, too. And like Dr. King, I know we’re at one point along that arc, a few big steps toward a world with less violence and more fairness.

Read more:

Effecting Change / Standing Up – True Tales Live program (PPMTV YouTube): Listen to Arnie talk about 34 years of campaigning to end the death penalty. He is the fourth storyteller in this video.

New Hampshire will live without the death penalty (Concord Monitor): Arnie tells the story of two state legislators who played key roles in end capital punishment in New Hampshire.

New Hampshire Public Radio interviews Arnie (Instagram)

“In the Halls of Power” interviews Arnie (YouTube)