This piece was written collaboratively by Willie Colon, Tony Heriza, Tonya Histand, and me with many other contributors. Nathaniel Doubleday curated the images shared here. This piece was shared on the opening day of the Centennial summit on April 20th, 2017. Take a look at the Centennial video “Love in Action” as well. – Lucy

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, a military draft was immediately introduced. Prison would be the new home for those who refused to fight. Young pacifists -- Quakers and others -- needed a way to serve their country nonviolently. Out of this need, the American Friends Service Committee was born.

During WWI, Service Committee volunteers drove ambulances in combat zones and rebuilt homes and roads. After the war, as hunger and malnutrition swept through Europe, AFSC began feeding millions of children-- in Austria, Germany and Poland -- with U.S. government funds arranged by Herbert Hoover. By the 1920s, a temporary Quaker “response” had become an enduring and highly regarded relief organization.

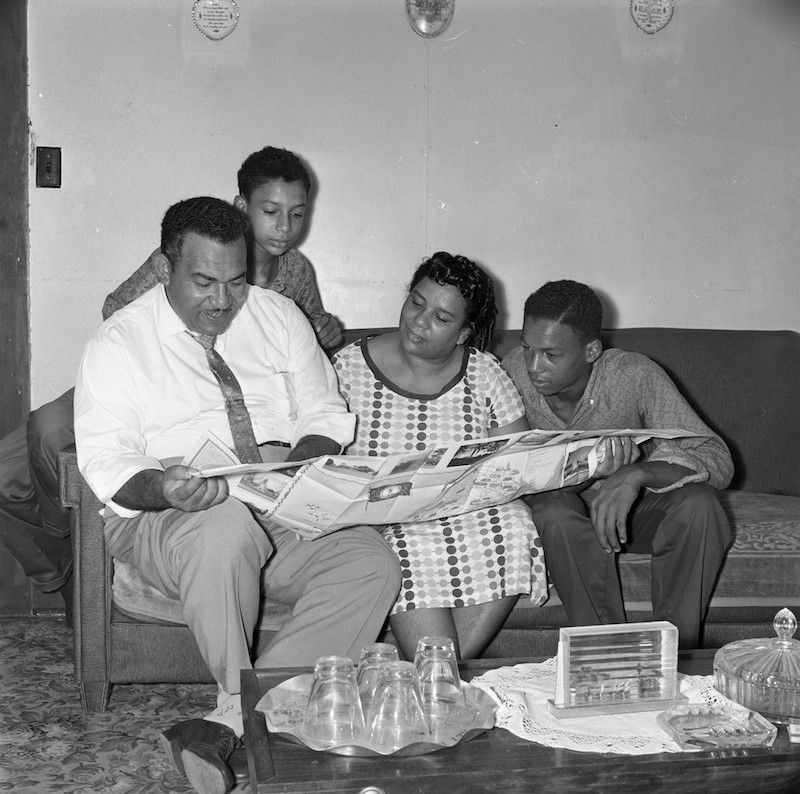

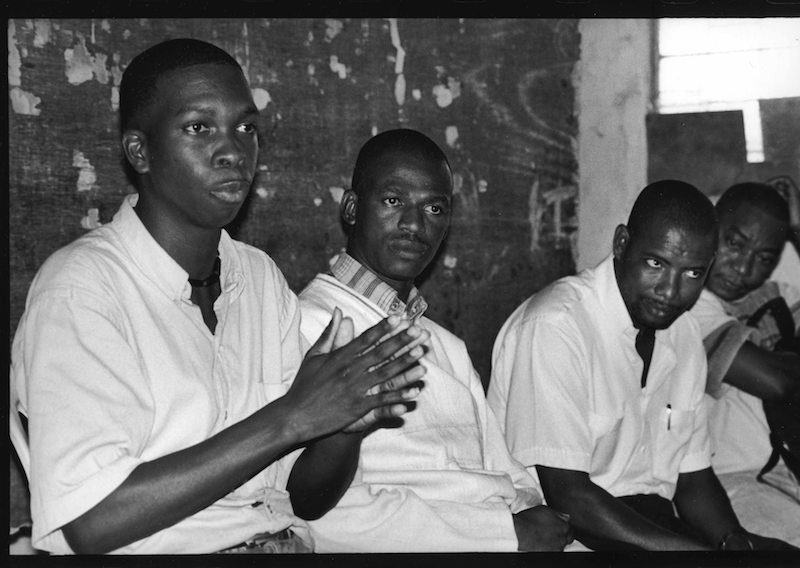

Back home, one of the earliest domestic issues AFSC addressed was racism. The “Interracial Section” was created in 1925 to challenge racial prejudice and violence in the United States. African American staffer Crystal Bird travelled across the country and spoke with thousands of white Americans about race and racism. Her efforts were followed by decades of work to combat lynching, expand employment and housing opportunities, and integrate public schools.

AFSC looked at its own practices, too, integrating work camps and Peace Caravans in the 1930s to help young people overcome the rigid segregation of the wider society.

The Great Depression brought a new focus on economic justice. A slump in the demand for coal left thousands of Appalachian miners unemployed, hungry and desperate. AFSC provided relief and supported economic alternatives, such as training in local crafts like furniture making – and the development of a model community where residents participated in a shared economy.

During the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s, AFSC joined British Quakers in feeding displaced women and children on both sides of the conflict. After Franco’s victory, the relief moved to the south of France, where Spanish refugees were soon joined by many others fleeing the Nazis. AFSC staff worked to assist people in these refugee camps and to secretly transport children to safety. Numerous “hostels” were created -- across Europe, in the U.S., and in Cuba -- to provide safe haven for tens of thousands of Jews.

In 1947, AFSC and the British Friends Service Council accepted the Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of Quakers everywhere for their work worldwide to heal rifts and oppose war. According to the Nobel committee, “The end of World War II brought a burst of AFSC effort, with Quakers engaged in relief and reconstruction in many of the countries of Europe, as well as in India, China, and Japan.”

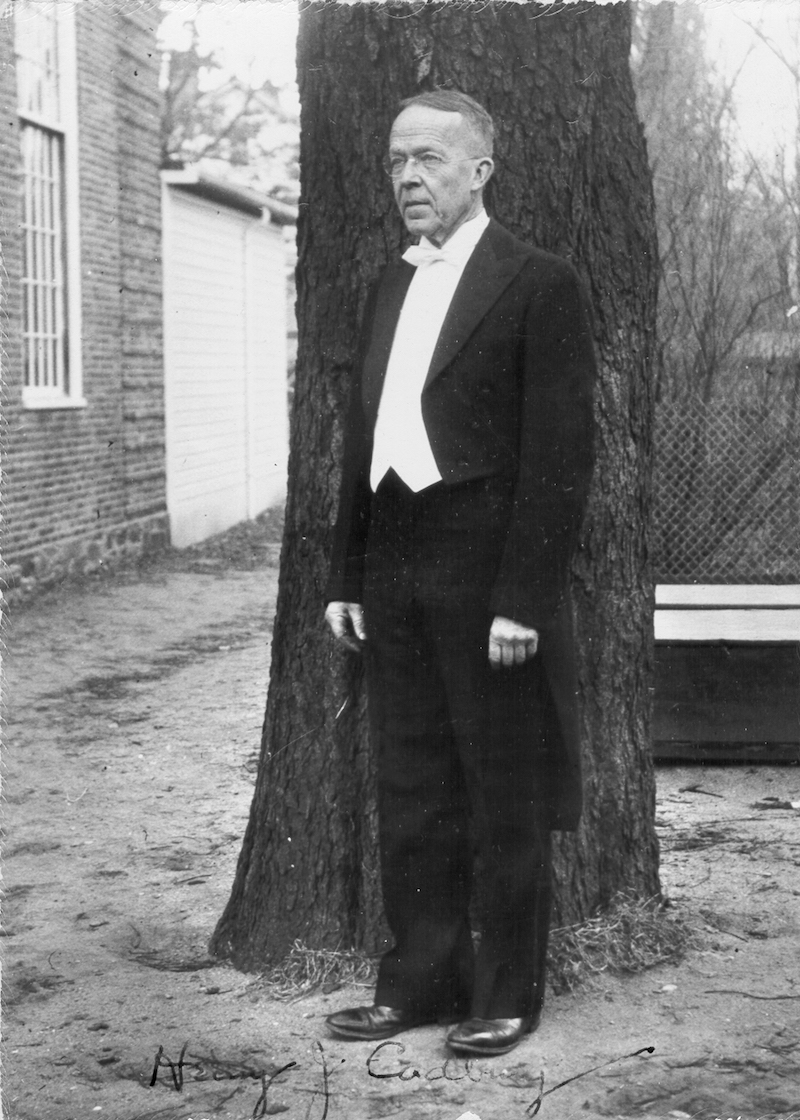

Henry Cadbury, who accepted the prize on behalf of AFSC, didn’t have a long-tailed coat. Luckily, AFSC was collecting used formal wear for the Budapest Symphony Orchestra at the time and a suitable coat was found among the donations. Henry borrowed it and wore it to the ceremonies in Oslo.

Following the 1954 Supreme Court decision that ordered the desegregation of public schools, AFSCs Southern Program helped Black families enroll their children in formerly white schools. In Prince Edward County, Virginia, where the school board closed their schools rather than integrate, we helped dozens of Black high school students find placement in northern homes and schools so they could continue their education.

From 1965-70, AFSC helped build the antiwar coalitions that challenged U.S policy in Vietnam. Bridging the divide between liberal faith groups and more radical antiwar resisters, we argued for a broad peace movement that included a wide range of groups. At the same time, we offered draft counseling to thousands of young men in the U.S. and provided medical aid and assistance to civilians on all sides of the conflict in Vietnam.

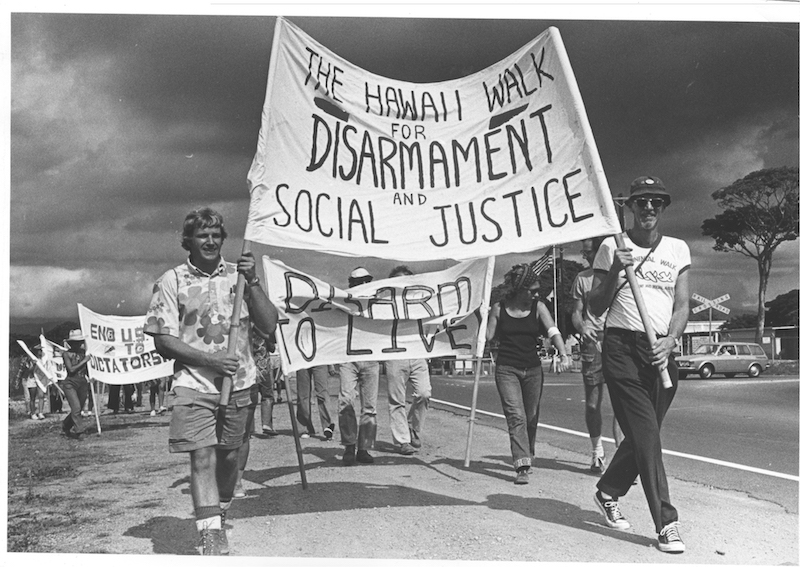

But opposing and developing strategies to address conventional war was only one strand of the search of peace. Since Hiroshima, AFSC has been engaged in efforts to halt nuclear weapons testing, the acceleration of the arms race, and the spread of nuclear technology.

We co-founded SANE (the Committee for SANE Nuclear Policy) and during the anti-nuclear movements of the 1970s and 80s, AFSC played a key role in teaching nonviolent resistance to the Clamshell Alliance in New Hampshire and to the Abalone Alliance in California. These movements brought the nuclear power industry to a near standstill.

The issues AFSC addressed continued to expand, and in 1975 the Service Committee’s institutional response to Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual concerns began when four staff and committee people sent out an open letter in which they acknowledged their homosexuality or bisexuality. They invited others to join them and over 200 people signed a “statement of support and solidarity.”

Later Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans initiatives in Philadelphia, Seattle and Hawai’i paved the way for AFSC’s Bridges Project, the first national information clearinghouse for and about LGBTQ youth. From the beginning, AFSC brought a unique intersectional approach to queer issues, highlighting how expressions of discrimination and oppression overlap in our society and amplifying the least heard LGBTQ voices: those of youth, people of color, the poor, the incarcerated, and the disabled.

AFSC also was an early leader in the long struggle to end apartheid. Our work included sending staffer Bill Sutherland to Africa to connect with liberation movements to help inform U.S. work on Southern Africa. Through Bill’s work, AFSC focused on how the U.S. government and businesses were supporting South Africa, and called for sanctions and divestment to force an end to apartheid. As the anti-apartheid movement grew, our Atlanta office led a successful nationwide boycott of the Coca-Cola Company. Ultimately, public opinion shifted and the divestment campaign contributed significantly to the fall of apartheid.

In the same period, AFSC staff member Daniel Ntoni-Nzinga used quiet diplomacy and all his program funds to build the religious coalition, COEIPA, into a powerful force that helped end the Angolan Civil War.

While most of our work is unheralded and behind-the-scenes, we have had moments in the limelight. In 1986, we walked the red carpet in Los Angeles. The Academy Award for Best Documentary Short Subject that year was awarded to “Witness to War,” a film produced by AFSC. The film told the story of Dr. Charlie Clements, who, after being discharged from the U.S. Air Force for reasons of conscience, went on to work as a physician amid El Salvador’s civil war.

In the late 1990s, AFSC began to support local peace-building efforts in Colombia. We worked with “peace communities” on the Pacific Coast, primarily Afro-Colombian and indigenous communities in southwest Putumayo that were resisting coercion by both the guerillas and the paramilitaries. We offered training in peaceful resistance and community building and provided material aid and human rights assistance to those who were displaced.

An ocean away, AFSC fed thousands of children and rebuilt destroyed homes and hospitals during the Korean War. We returned to Korea in the early 1980s with people to people exchanges with the DPRK (or North Korea). Then, during a famine in the late 1990s, AFSC responded with emergency relief. By 1998, we had established an ongoing agricultural assistance program with cooperative farms. As one of the few American organizations working continuously in North Korea for more than three decades, AFSC has made significant contributions to the country’s food security while creating opportunities for meaningful exchange.

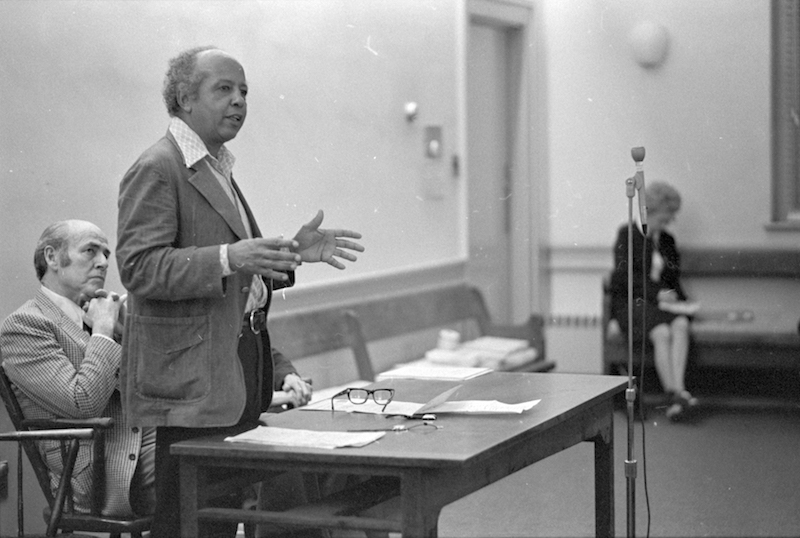

For Quakers – and AFSC - justice has always been a central concern and inextricably linked to the search for long-term, sustainable peace. We’ve challenged police brutality, rallied faith groups to resist the death penalty, and exposed the evils of solitary confinement. Recently when 30,000 prisoners went on a hunger strike to protest solitary confinement at Pelican Bay Prison, AFSC’s Laura Magnani represented the prisoners in negotiations that led to a landmark legal settlement limiting the use of solitary confinement in California. Today, ending mass incarceration and for-profit prisons are at the center of our peace with justice agenda.

We are also committed to supporting a new generation of activists. AFSC’s Tyree Scott Freedom School in Seattle, and the follow up program YUIR (Youth Undoing Institutional Racism), provide young people with an antiracist framework and prepare them to take action for social change in their schools and communities.

In one recent victory, years of intense pressure by young anti-racist organizers in Seattle resulted in a dramatic downsizing of a proposed youth jail, a pledge of $600,000 by city council to develop alternatives to juvenile detention, and a city council resolution calling for an eventual end to the detention of youth. The AFSC Freedom School model has recently been expanded to St. Louis, St. Paul, and Pittsburgh.

Our decades of experience influence our work today, as we accompany migrant and immigrant movements and build alliances with others who share our vision.

Today, hundreds of congregations across the U.S. are part of a new sanctuary movement to protect immigrants and refugees in our communities. In Colorado, Jeannette Vizguerra, a longtime immigrant and labor leader, has been challenging her deportation for eight years with AFSC support. She recently entered sanctuary at the First Unitarian Society of Denver after being denied a stay of her deportation.

In the face of growing harassment and hostility toward many groups, AFSC is also promoting a broader concept of “Sanctuary Everywhere,” encouraging active engagement in creating safe spaces for each other and challenging hateful speech and actions, wherever they occur.

We know that peace and safety are built on foundations of love and inclusion, not oppression and discrimination. As we partner with people across the country who are challenging fear and hate, we offer hope—hope that compassion will win out over fear, and that together we can create the open, welcoming communities we all deserve.

We are unshakable in our commitment to peace, justice, and equality.

We will resist any attempt to sacrifice the rights of the marginalized.

We will question any efforts to add comfort to the privileged.

We will speak truth to power – as often as it takes to be heard.

We will build bridges for dialogue and reconciliation.

And we will stand with groups fearing violence and persecution and support their movements to overcome injustice.