Millions of immigrants in the U.S. will be affected by the court's decision. Here are two of them.

By Kimberly Krone and Lisa Vives

Mariam’s story

Seventeen-year-old "Mariam" is a young girl with big dreams. If all goes right, she'll be a lawyer or work in business.

But unlike other girls her age, her future will be decided not by her grades or her family income but by the justices of the Supreme Court.

On April 18, the nation's highest judicial body will hear oral arguments in the case U.S. v. Texas, which challenges the injunction the lower courts placed on President Obama’s executive actions on immigration.

If the injunction is lifted, the president’s action would expand eligibility for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which grants young people who immigrated to the United States as children temporary protection from deportation and permission to live and work in the U.S. It would allow millions of parents of U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents the same protection under the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA) program.

The DACA and DAPA programs Obama launched through executive action on Nov. 20, 2014 could shield as many as five million immigrants from deportation. Their cases were placed on hold since a federal judge ruled that Texas and 25 other states have a legitimate basis to challenge them. The justices must weigh whether a state that voluntarily provides a subsidy to some immigrants has standing to bring the case.

Mariam, who is now a high school student, came to the U.S. four months too late to qualify for the original Deferred Action program, which gave certain undocumented immigrants who entered the country before their 16th birthday and before June 2007 the right to receive a renewable two-year work permit and exemption from deportation.

A heavy cloud over her life seemed to lift when it appeared that she could be covered by the expansion of DACA. But the program is frozen pending the court review. In the meantime, she emails her lawyer daily, checks on the status of the lawsuit, and asks anxiously whether she might still be able to work, apply for a driver's license, and go to college.

This year Mariam and her schoolmates will graduate and move on. But Mariam must wait on the Supreme Court’s ruling before she can start planning her future.

Her lawyer shares her frustration. But at this point, there's little they can do.

Luz Maria’s story

Meanwhile, Luz Maria, originally from Guatemala, is trapped in a similar bind.

Meanwhile, Luz Maria, originally from Guatemala, is trapped in a similar bind.

Her partner for many years – a police officer – had an uncontrollable temper. It reached the point where his beatings nearly killed her.

But in Guatemala, there is little protection for victims of domestic violence. This led her to flee, in 2005, to the U.S. for safety, only to learn that at the time the U.S. did not protect survivors of severe domestic abuse under its asylum laws.

And when it began to do so, in 2014, it was long after the one-year deadline that the U.S. gives asylum seekers to present their case. If she were to apply and not be successful, she would face deportation in what lawyers call “removal proceedings.”

Faced with these options, Luz Maria took the chance to live in the U.S. where she was safe. She has remained in limbo for 11 years without any immigration status because of the existing asylum restrictions. During that time, she found a new partner and they had children together in the U.S. She lives in New Jersey with her four U.S. citizen children, three of the four children she had in Guatemala, and a U.S. citizen grandchild.

To contribute to the household, Luz Maria does factory work. With the income from her partner and oldest son who works full-time, they just barely cover their expenses. Apart from the U.S. citizen children, only one family member has immigration status; one of her sons, the last to arrive from Guatemala, applied for and was granted asylum.

If the injunction on the executive actions is lifted, Luz Maria would be able to apply for relief from deportation under the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans program. But until the Supreme Court makes its ruling, her legal status in this country is uncertain.

Working for change, hoping for relief

In New Jersey where Mariam and Luz Maria live, about 250,000 immigrants would be eligible to apply for the expansion of DACA and DAPA. Along with their families and communities, they are looking to the Supreme Court with hopes of relief. But immigrants and immigrant rights activists aren’t just waiting in silence. They are actively working to educate their communities, shift public opinion, and change public policy.

The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) has worked for decades with immigrants and refugees to advocate for immigrant rights. In New Jersey, AFSC works to prepare community members for the expansion of DACA and DAPA, conducts informational sessions at its office and in the community, and regularly provides advice and legal counsel to those who are eligible for DACA and DAPA. AFSC has also been active in the Supreme Court case, signing onto an amicus brief requesting the Supreme Court review U.S. v. Texas.

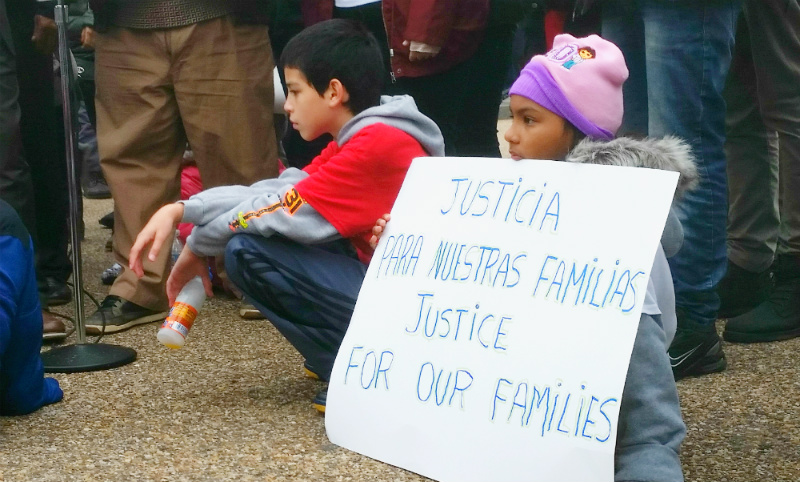

And immigrants, activists, and advocates in New Jersey and across the country are participating in grassroots mobilizations to effect change. AFSC staff and community members impacted by DACA/DAPA have spoken to the media and at public events about why DACA and DAPA must be implemented. One such event is planned for April 17, when AFSC and organizations from across New Jersey will gather for a rally in Jersey City to urge the U.S. Supreme Court to keep families together by upholding DACA and DAPA for the entire nation.

There is a lot at stake in the Supreme Court’s decision, for Mariam, Luz Maria, their families, and millions of others. But one thing is certain: Regardless of the outcome of the case, the struggle for just, fair, and humane immigration policies will continue.

About the authors

Kimberly Krone is the youth justice attorney within the AFSC New Jersey Immigrant Rights Program, where she provides legal representation to immigrant children and youth, including those who are detained.

Lisa Vives is a volunteer in social media and communications at the AFSC New Jersey Immigrant Rights Program. In her free time, she writes a weekly newsletter on Africa which is submitted to African-American media nationwide. She learned her trade at The Jersey Journal, where she covered gentrification.