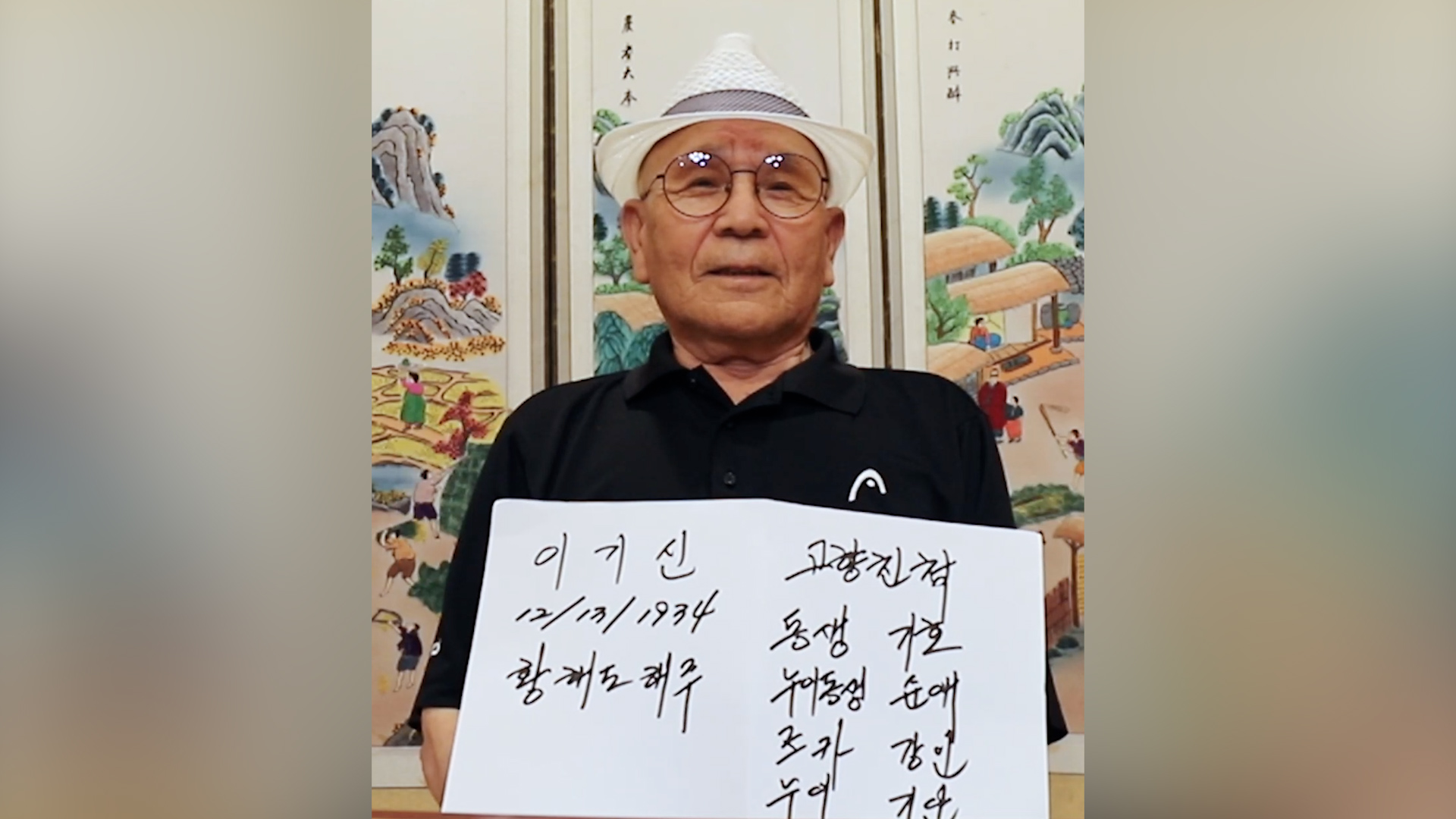

Ki-Shin Lee has not seen his siblings in North Korea in 26 years. Watch this video to hear his story.

"Before I die, my last wish is to see my two youngest siblings again,” said 90-year-old Ki-Shin Lee, with tears glistening in his eyes. “I’m hoping for an opportunity to visit North Korea through the United States … and say that I’m sorry to them.”

This past summer, I had the opportunity to interview 26 elderly Korean Americans like Mr. Lee who remain separated from their family members in North Korea because of the enduring conflict and division on the Korean Peninsula. Thanks to the support of AFSC, I was able to visit people in cities across the United States, including in New Jersey, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Virginia, California, and Georgia. They shared with me memories from their childhood, as well as messages they wanted to send to their family members who remained in their hometowns in North Korea.

I began volunteering on behalf of elderly Korean American divided families seven years ago through an organization called Divided Families USA. We are advocating for the U.S. government to work with North Korea to establish a formal mechanism for face-to-face and video reunions. After my own grandfather passed away last year without getting to reunite with his older brother in North Korea, I felt an even greater sense of urgency to record these stories before time runs out for this generation.

I began this interview project with the hope it could help facilitate closure, healing, and reconnection for these divided families. Moreover, by partnering with the nonprofit organization Korean American Story, I hope that this project serves as an educational resource for many. It’s vital that we raise awareness about this living history—especially among younger generations of Korean Americans—as well as the human impact of the Korean War and how it continues to affect so many today.

Here are three things to know about Korean American divided families.

1. Despite many who desire to visit their hometowns, Korean Americans lack a formal mechanism of reconnecting with their family members in North Korea.

The Korean Peninsula continues to suffer from an unresolved state of war. Nowhere is the human impact of conflict more apparent than in the separation of families, including Korean Americans like Mr. Lee. He immigrated to the U.S. in 1997 believing that it would be easier for him to visit his hometown in Hwanghae Province (in what is now North Korea). That year, he was able to travel to his hometown to reunite with his siblings and start to exchange handwritten letters twice a year with them.

But in 2017, the U.S. implemented a ban on U.S. citizens traveling to North Korea (in addition to several other countries as part a broader travel ban under the Trump administration). Since then, Mr. Lee has not been able to travel to North Korea nor exchange any letters with his relatives there.

Although inter-Korean cooperation has led to official reunion programs—such as in-person meetings, video conferences, and letter exchanges—these opportunities have only been accessible to North and South Korean citizens. Thus, Korean Americans have had to resort to alternative means of reconnecting with their family in North Korea, such as through private brokers in other countries or personal connections with the DPRK government.

2. Time is running out for these elderly Korean Americans, and interest in reunions extends to younger generations.

Because most divided family members were separated during the period of active conflict of the Korean War (1950-1953), the overwhelming majority are nearing the end of their lives. The advanced age and deteriorating health of this generation (most who are now in their 80s and 90s) highlight the need for governments to prioritize this issue. Many of my interviewees left behind their spouses and younger siblings in North Korea, thinking that they would only be saying farewell for a few days.

Although time is running out for this first generation of divided families, their hope of visiting their hometowns is often passed down to their children and grandchildren. I met many younger Korean Americans who seek to carry on their parents’ legacy by paying their respects to their ancestral homes and meeting with their extended family. Thus, this sense of kinship between Korean Americans and their families in North Korea is not limited to immediate siblings or parents who they can remember. Their desire for connection extends to cousins, nieces, and nephews who are part of their family tree.

3. Korean American divided families are not monolithic in their political views.

While all of my interviewees shared a longing for their hometown and miss their family members, they had vastly different ideas about how this should be achieved. For instance, some hope that their family members in the North can enjoy the same level of civil and religious rights, while others accept the need to navigate the current political structures. Moreover, some who had the opportunity to visit their hometowns in the past wish to return, while others feel burdened by the pressure to send remittances back to their relatives and simply wish to ascertain whether they are still alive.

The level of public support for family reunions and calls for peace between the U.S. and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK/North Korea) continues to rise. But deadlocked negotiations and the entanglement of humanitarian issues with security challenges have stymied any of initiatives for re-engagement.

Family reunions could provide a foundation for trust building and reconciliation between the two countries. At the same time, government officials should prioritize the needs of those who yearn to return to their hometowns and reunite with their families before it is too late.

Here’s are some steps you can take to support Korean American families:

-

Consider joining an intergenerational, cross-community effort calling on Congress to pass the Peace on the Korean Peninsula Act! The bipartisan initiative would require the State Department to review the travel ban and provide a roadmap for peace that could finally end the 70-year conflict on the Korean Peninsula.

-

Visit my website to learn more about the project.

-

Get more updates on the message archive at KoreanAmericanStory.org.