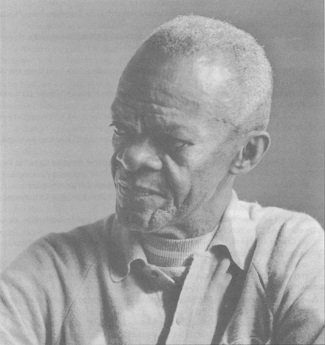

Note: Barrington Dunbar (1901-1978), like many others, challenged white Friends to take a more active approach in addressing racism and white supremacy. He asked Friends to show their support for the Black Power Movement even though its violent rhetoric often felt alienating to pacifist Friends. Although we cannot know what Friend Barrington would have to say about current events, it is easy to imagine him challenging white Friends to support the Black Lives Matter movement today. Barrington was very active in the Religious Society of Friends, and his words are still relevant for Friends (and others) today.

His essay "Black Power's Challenge to Quaker Power" first caught my attention in the book, Black Fire: African American Quakers on Spirituality and Human Rights, published by Quaker Press of Friends General Conference in 2011. Published first in 1968 by Friends Journal, this essay challenges Friends to see the hidden violence that operates in white communities and highlights the necessity of doing anti-racism and social justice work as an extension of our belief that there is "that of God" in everyone. Please consider sharing this essay with your Quaker meeting. Queries for worship and discussion can be found at the bottom of the page. - Greg Elliott

Black Power’s Challenge to Quaker Power

Vital religious experience can provide the power to overcome the world. Gandhi and his followers experienced this, as did the early Christian church and the early Quakers. Corporate worship deepens the commitment of believers and can help them to stand firm against tyranny and oppression when they are laboring to bring about needed social reforms. For early Quakers, such activity was the extension of worship beyond the gathered community into a world divided by hatred, fear, and exploitation.

William James described eighteenth-century Quakers as a “people among people”—a gathered sect, a religious group who saw as their mission the creation of a new society. Then and later the meeting for worship must have been a living fellowship where a social reformer like Levi Coffin, in Indiana and Ohio, could come to share his concern for the slaves and to wrestle with Friends to gain their love and understanding and their support in his work of helping slaves escape to freedom through the Underground Railroad.

This close connection between work and worship—between the gathered community of the Meeting and the wider community—seems to be a missing ingredient in the practice of the Quaker Meeting today, which often tends to serve the purpose of a social club where people meet to pursue their common interests in isolation from the rest of the community. We attend meetings to escape the agonies of an unjust society and to find personal refuge among like-minded Friends. Because our hearts are not stirred or our minds made sensitive to the injustices of the communities in which we live, we accommodate ourselves to a whole system of personal and group relationships in our neighborhoods and places of business—a system that has served to reinforce the assumption of white superiority. This way of life denies that there is that of God in every man, the vital message of Quakerism that provides the basis for the “blessed community” in which everyone can achieve freedom from want and fear and can realize his full potential as a human being.

We Friends must re-examine our nonviolent testimony in the light of today’s realities. Suffering humanity sees us as another group of white Americans who are deeply implicated in the social-political-legal military system that has contributed to the violence of our times. Most Friends in America belong to the white middle class; even if we do not knowingly participate in efforts to keep nonwhites from having access to opportunity and power, we condone it by our silence. We have accepted the estrangement of nonwhites in ghetto communities as the “American Way.”

To dispossessed and disadvantaged nonwhites, the nonviolence that Friends profess sounds trite and hollow; it complicates our efforts to communicate with them. Some Friends are like the Pharisee who went to the temple and prayed: “Thank God I am not like other men.” “Thank God,” we say, “we are not open advocates of violence like Rapp Brown or Stokely Carmichael.” But these aggrieved young men would say: “For over three hundred years you have been dealing violently with us by denying us the right to participate fully as citizens of the community.”

Humility is much needed among Friends, as is the acknowledgement that we share the guilt for the crucial and explosive nature of the racial situation in America. Through humility we may gain repentance and learn to respond with love to men like Brown and Carmichael, in spite of grievous wounds. To love one’s enemy and to turn the other cheek are the zenith of Christian love.

Friends who have experienced love in the fellowship of the “gathered community” can demonstrate to the wider community what love can do in the following ways:

- We need to nurture the Inner Light—the source of the phenomenal power of the eighteenth-century Quakers. “Quaker Power” can be as effective as “Black Power” in speeding up revolutionary changes.

- We need to listen in love to the black people of America and to submit ourselves to the violence of their words and actions if we are to identify truly with their anguish and despair.

- We need to understand, to encourage, and to support the thrust of black people to achieve self-identity and power by sharing in the control of institutions in the community that affect their welfare and destiny.

- We must invest our resources—money and skill—to provide incentives for black people to develop and control economic, political, and social structures in the community.

- We must support the passage of antipoverty legislation leading to programs that will remedy the deplorable economic and social conditions existing in urban ghettos.

- We must oppose racial injustice wherever it is practiced: in the neighborhood where we live, in our places of business, and in our contacts with the wider community.

Queries

How can "Quaker Power" speed up "revolutionary changes" in our community/communities? How might it play a role in transforming systems of oppression?

How can we show "what love can do" for racial justice? Is there anything that should be added to Friend Barrington's list?

Is my Quaker meeting more than a "social club" for people with "common interests?" Who or what might be missing from our "Beloved Community?"

Sources

"Black Power's Challenge to Quaker Power" (c) 1968 Friends Publishing Corporation, republished with permission.

(Subscribe at http://www.friendsjournal.org/subscribe/)

"Barrington Dunbar," Black Fire: African American Quakers on Spirituality and Human Rights, edited by Harold D. Weaver, Jr., Paul Kriese, and Stephen W. Angell, with Anne Steere Nash; forward by Emma Lapsansky-Werner. Quaker Press of Friends General Conference (Philadelphia, PA: 2011).