Note: Stephen McNeil is Assistant Director for Peace-building Programs in AFSC's West region. On Aug. 25, 2013, after traveling from San Francisco and attending the 50th anniversary March on Washington to Realize the Dream, Stephen helped to organize a public event at Friends Meeting of Washington commemorating the life of Bayard Rustin, one of the march's chief organizers and a committed Quaker. - Madeline

Bayard Rustin, Quaker, occasional AFSC staffer, and key contributor to the seminal AFSC paper, "Speak Truth to Power," is finally receiving his due: African-American, gay, and an organizer 50 years ago this month of the March on Washington, Rustin will be awarded posthumously the Presidential Medal of Freedom in November.

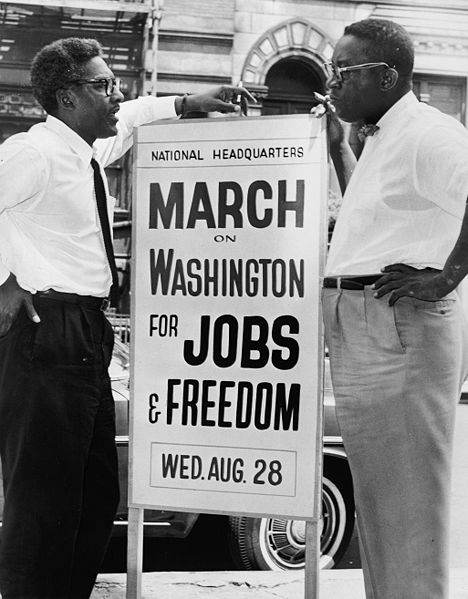

Bayard Rustin not only organized to bring and care for thousands of protesters to the march, he was also able to ensure that the messages of nonviolent direct action and political change were clearly articulated and known by all.

When the D.C. authorities called out thousands of police and National Guard for security, organizer and currently DC’s nonvoting Congressional Representative, Eleanor Norton, said that Rustin and the march organizers gathered 2,000 march marshals, and Rustin “drilled hundreds of off-duty black police officers and firefighters who had volunteered to serve as marshals. He made them take off their guns and coached them in the techniques of nonviolent crowd control he had brought back from a pilgrimage to India.”

Rachelle Horowitz (the transportation organizer) said, “We used to go out to the courtyard to watch. It was like, see Bayard tame the police.”

Rustin saw the march as part of a movement that included both Gandhian direct action and mass protests (The New York Times had calculated up to 70,000 people protesting a month nationwide prior to the march). This was an opportunity to get the message out to the U.S. public and the world.

Some of Rustin’s tactics included spending time with the foreign press corps and having thousands of red, white, and blue standard signs that people picked up as they marched, carrying unified messaging.

On Democracy Now Amy Goodman related that, “There’s a funny scene in Brother Outsider when there is Bayard, 5:30 in the morning, on the Mall, August 28, 1963. All the press is around him, and of course there’s no one there. This is very early in the morning. The press is saying, 'So, see? No one’s here.' It’s 5:30 in the morning. And he said he took a white piece of paper, a blank piece of paper, that they couldn’t see it was blank, and he looked at his clock. He said, 'No, everything is going according to plan right now.'"

On Sunday, Aug. 25, I helped to lead meeting for worship co-hosted by AFSC, the Friends Meeting of Washington, and FCNL to celebrate the life of Bayard Rustin as a Quaker. In giving vocal ministry, those gathered spoke to Rustin’s commitment to Quakerism and his call to act.

We then showed the film Brother Outsider and had a lively audience discussion with Mandy Carter of the National Black Justice Coalition and Bayard Rustin 2013 Commemoration Project, and David McReynolds of the War Resisters League, who had worked with Rustin. We debated not only issues of social change, but of political compromise and conflicted sexuality, as well.

We then showed the film Brother Outsider and had a lively audience discussion with Mandy Carter of the National Black Justice Coalition and Bayard Rustin 2013 Commemoration Project, and David McReynolds of the War Resisters League, who had worked with Rustin. We debated not only issues of social change, but of political compromise and conflicted sexuality, as well.

Like anyone praised highly after their death, Rustin had his inconsistencies. But we did come away in awe of his ability to maintain the practice of resistance to injustice. As the recent collection of his letters edited by Michael Long proclaims, “I Must Resist.”

In the 1980s, African-American and gay man Joe Beam invited Rustin to contribute to a landmark anthology on black gay activists and writers. As Bayard Rustin had come late to the movement, he declined, writing to Beam: “My activism did not spring from my being gay, or, for that matter, from my being black. Rather, it is rooted fundamentally in my Quaker upbringing and the values that were instilled in me by my grandparents who reared me. Those values are based on the concept of a single human family and the belief that all members of that family are equal.”

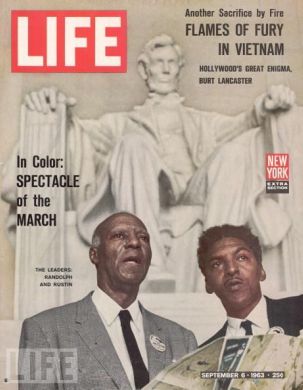

Walter Naegle, who was Bayard Rustin’s partner from 1977 until Rustin’s death in 1987, now the archivist for the Bayard Rustin Estate, noted that “all of the Big Six… the leaders of the Big Six civil rights organizations that issued the call for the march—Mr. Randolph, Roy Wilkins, Dr. King, John Lewis, Jim Farmer, Whitney Young—they’ve all received the Medal of Freedom. And  Bayard was kind of this hidden seventh, if you will, kind of behind the scenes pulling the strings and organizing, with an awful lot of very dedicated volunteers. He didn’t do it by himself.”

Bayard was kind of this hidden seventh, if you will, kind of behind the scenes pulling the strings and organizing, with an awful lot of very dedicated volunteers. He didn’t do it by himself.”

Indeed, fellow organizers such as Rachelle Horowitz, Tom Kahn, and hundreds of others were acknowledged by march “Deputy Director” Rustin himself after he and march director A. Philip Randolph appeared on the cover of Life magazine the week after the march. Rustin wrote, “Don’t be fooled by the mass circulation magazines into believing that the success can be credited to one person….the real credit goes to thousands of unknown people throughout the country who gave their time and energy to make sure that the nation would never forget August 28, 1963. I think they have achieved their objective.”