A photo of district constituents in a meeting with Representative Jimmy Gomez’s office to discuss H.R. 1369 Peace on the Korean Peninsula Act during Korea Peace Advocacy Week.

Seventy years ago this month, Koreans across the peninsula were in the midst of a three-year period of dislocation, separation, and violence, which has come to be known in the U.S. as the “Forgotten War.” While neither the Korean War nor its effects have been forgotten by those who live on the peninsula, active fighting ceased with the signing of the Korean Armistice agreement on July 27, 1953.

To commemorate the 70th anniversary of the armistice and call for an official end to the unended war, a diverse coalition of faith leaders, multi-generational Korean Americans, peace activists, humanitarian workers, scholars, and veterans will gather together in Washington, D.C from July 26 to 28.

This post offers some background on the Korean Armistice, the human toll of the unended war, and an overview of AFSC’s efforts to build peace between the peoples of Korea and the U.S.

1. 70 years of militarized tensions

War is often described like a sudden rupture of violence, as if it were a cannon fired into the air. However, conflict on the Korean peninsula began to simmer immediately following the liberation of Korea from colonial Japan in 1945 as both the Soviet Union and the U.S. established an occupying presence on the northern and southern halves of the peninsula. In 1950, this conflict boiled into active fighting up and down the Korean peninsula that lasted for three years. Active hostilities were halted with the signing of the armistice agreement in 1953 by The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK or North Korea), The People's Republic of China, and the United Nations represented by the U.S., but the ongoing state of war was never resolved with a peace agreement.

The armistice agreement brought with it the establishment of the roughly 150-mile-long and 2.4-mile-wide Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) at the 38th parallel of the peninsula. This line across the peninsula was chosen by two American officers and proposed to the Soviet Union as a halfway point of division that would keep the capital city of Seoul under U.S. control. While the border between the two Koreas is designated as a demilitarized zone, it is in fact highly militarized on both sides. For a portion of the nearly 330,000 South Korean men who must complete mandatory military service each year, the DMZ is a common site of deployment. In addition, for the past 70 years the U.S. and South Korea have conducted joint military exercises near the DMZ on a nearly annual basis in order to synchronize their military posture against North Korea.

This is the legacy of the Armistice Agreement—division, deployment, and drills for war. Continued military posturing only feeds an ever-tightening cycle of aggression on the peninsula. However, the effects of the unended war reach beyond uniformed soldiers into the daily lives of civilians in both Korea and the U.S.

2. The Unended War's continued toll on people in Korea and the U.S.

For the tens of thousands of surviving divided family members who remain separated by a perpetually fractured peninsula, the unended war serves as a blockade to meaningful progress. The aging members of Korean and Korean-American families who have relatives in the north have been unable to reunite with family members for over 70 years. For many of these elders, time is running out.

The unended war also serves as a barrier to the principled engagement needed to improve the relationship between the U.S. and North Korea. Further isolation, sanctions, and imposition of the 2017 travel ban limit the people-to-people connections between Americans and North Koreans needed to build mutual understanding. Such understanding and trust is the foundation of the local partnerships that organizations like AFSC rely on to collaborate on humanitarian assistance, such as introducing a new method for transplanting rice seedlings to farmers.

Repatriation of remains to the families of the nearly 5,300 missing U.S. servicemen is also one of the concerns repeatedly obstructed by a perpetual discourse narrowly focused on state security. Efforts to retrieve these remains continue to get lost in political limbo. Without an end to the war and the building of trust between the U.S. and North Korea, this recovery work will continue to be pushed to the back burner.

3. AFSC’s work to promote peace between people in the U.S. and Korea

While the past 70 years have included much division and prolonged structural violence, there is also a long history of work towards peace and justice on the Korean Peninsula. AFSC began its work in Korea in 1953, answering the call of the UN to provide assistance to refugees in the south through food, medicine, and bedding as well as rebuilding a hospital. We became the first U.S. public affairs organization to enter North Korea in 1980 when we sent a delegation to build mutual understanding and contribute to reduction of tensions between the U.S. and North Korea. 70 years following the war, AFSC is still working to promote peace and engagement between the U.S. and North Korea.

From June 5th to 9th, AFSC and other co-organizing partners gathered with constituents from across the U.S. to share stories and urge congressional representatives to support legislation to end the Korean War. By the end of Advocacy Week, five new House Representatives had signed on to support the Peace on the Korean Peninsula Act.

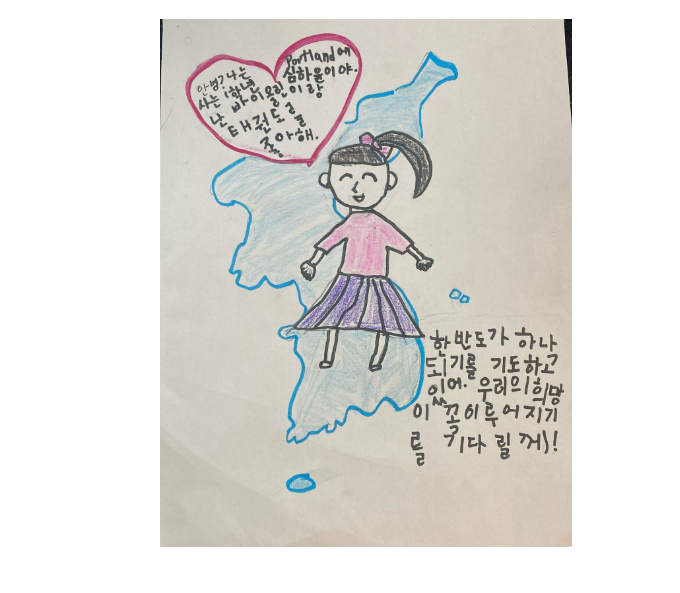

We have also been collaborating with Okedomgmu Children in Korea, a South Korea-based partner, and ReconciliAsian, a California-based partner, to prepare an art exhibition called Drawing Hope which will take place in Los Angeles this fall. This project promotes the peaceful encounter of children from North Korea, South Korea, and the U.S. through the sharing of art work. It is this type of exchange that will allow people to humanize each other and begin to heal the entrenched conflict of the past 70 years.

A picture from the Drawing Hope exhibition of a girl standing on the unified Korean Peninsula saying, “Hi, I’m HaYoon Shim. I’m in 1st grade and I live in Portland. I like violin and Taekwondo. I’m praying the Korean Peninsula will be unified. I’ll eagerly await for our hope to come true!”

This July, as the Armistice Agreement reaches its 70th anniversary, AFSC and several other peace advocacy groups are co-convening a national mobilization in Washington, D.C. to end the Korean War. For three days, we will advocate, pray, picket, and speak for an end to the unended war. Seven decades is far too long.

If you would like to support our work to bring an official end to the Korean War and promote peace between the U.S and North Korea through people-to-people engagement, you can tell Congress to pass the Peace on the Korean Peninsula Act and to invest in our communities instead of weapons and war. Signing the Korea Peace Appeal also helps support the international campaign calling for an end to the Korean War.

You can also read more about our North Korea Program here.