A mother and her 1-year-old child from Afghanistan are among the migrants detained in Costa Rica after being deported from the United States. Marcia Aguiluz Soto/AFSC

On a recent Thursday morning, I set foot in a facility that few outsiders have seen in recent months: Costa Rica’s immigration detention center. I was part of a group representing the only organizations granted access to the facility since February. That’s when 200 migrants—including 80 children—arrived in Costa Rica on two deportation flights from the United States and were detained at the center.

These individuals were not from Latin America, let alone Costa Rica. They were from Afghanistan, Russia, Armenia, Iran, China, and other Asian countries. None of them wanted to be in Costa Rica. Most had not been told by U.S. immigration authorities where they were being taken. Many had been ripped from their families, who were still in the U.S.

The arrival of these migrants in Costa Rica is one result of the Trump administration’s broad effort to deport millions of people from the United States. Around the same time that these deportation flights arrived in Costa Rica, the U.S. sent hundreds of migrants to Panama, where they were detained in a hotel in Panama City for weeks. The U.S. has also deported at least 238 people to El Salvador, where they are now locked up in a notorious mega prison with little or no access to legal counsel.

There have been fewer news stories about the deportation flights to Costa Rica. But the impacts on these individuals and their families have been no less cruel.

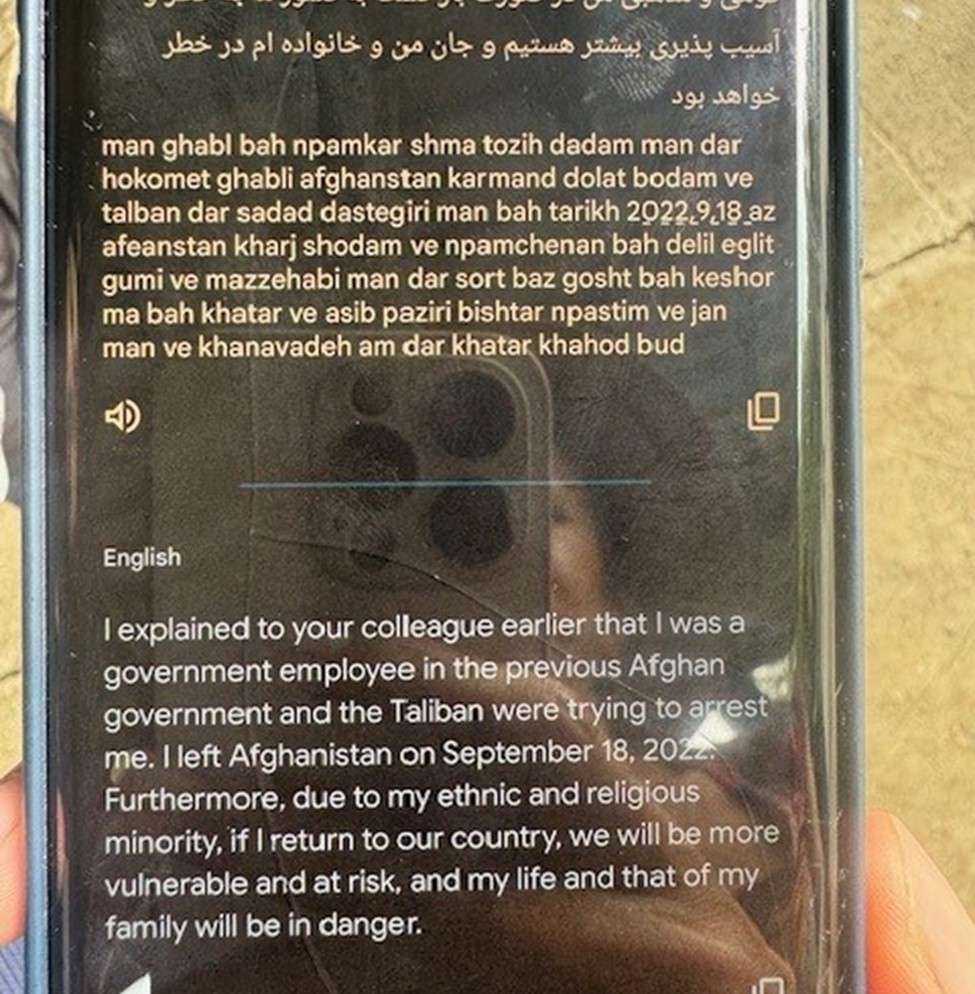

Advocates spoke with people detained using Google Translate on their phones. Marcia Aguiluz Soto/AFSC

Detained and displaced

On the Thursday that our delegation visited the detention center (known by its Spanish acronym, CATEM), we were politely received by its director and another official from the Directorate of Integration. They wanted us to know that they were fulfilling their responsibilities to care for the migrants they were detaining.

Our group was given one hour and 20 minutes to walk through the detention center and speak with as many people as we could. Sitting on the floor, in 88-degree heat, our group began our most important task: letting these individuals know that they have rights and that we were there to listen.

In that short time, we managed to talk to 24 people from 13 countries, speaking eight different languages. With few English speakers and none who spoke Spanish, we relied on Google Translate, typing into our phones and showing each other translations to communicate.

I talked with four women from Russia and Armenia. They were there with their children, ages 3 to 12. They told me about their difficult journeys from their native countries to the United States. All of them had fled political persecution and could not return. One of them had nearly been raped in Mexico.

All of them suffered abuse, horrific conditions, or violations of their rights while in detention in the United States—families torn apart, weeks locked away without natural light, and their right to seek asylum denied despite legitimate fears of returning to their home countries. None of them were told by U.S. immigration authorities where they were being deported.

One of the women told me, “My husband and 13-year-old son are there—we want to see them. We have a right to be with them.”

Another woman typed into her phone: “In the U.S., we were locked in a room for more than 20 days. They mistreated us, handcuffed us, lied to us. We didn’t know they were sending us to Costa Rica. We’re trapped. We can’t go back. We’ve lost hope. Please help us.”

Although conditions at CATEM are far better than U.S. detention centers, migrants are still being deprived of their freedom. Marcia Aguiluz Soto/AFSC

A shelter turned detention center

While conditions at CATEM are better than what migrants experienced in the U.S., it is still a detention center. People are being held against their will, with their documents confiscated, and their movement restricted.

This is a major shift from CATEM’s original purpose as a shelter where migrants could voluntarily come and go, get a meal, and stay overnight before continuing their journeys. Historically, Costa Rica has been known as a safe haven for refugees. But that changed in 2022, when the Chaves government imposed asylum restrictions, making it harder for people seeking protection.

Today, only 94 of the 200 migrants who arrived on the U.S. deportation flights remain at CATEM. Costa Rican authorities would not tell our organizations where the others are now. We fear they were forced to return to their home countries.

None of the migrants we spoke with at CATEM want to stay in Costa Rica, where they struggle with an unfamiliar language and culture, unbearable heat that has made many sick, and a complete lack of support networks. Most simply want to be reunited with loved ones in the U.S. Others hope that other countries that are closer to their cultural or linguistic realities—such as Canada, France, or Australia—could welcome them.

Exactly two hours after arriving at CATEM, we were asked by officials to leave because our time was up. But the people being detained still wanted to talk, so after we left the facility, we continued speaking with them through the chain-link fence surrounding its grounds. They wanted so badly to be heard.

Since the visit, I have kept in touch with some of the people I met via WhatsApp. The question that breaks my heart keeps coming up: Can you do something for us?

And I ask myself: What can we do? We likely can’t solve all the problems they face, but we can help ensure they have access to some rights and are able to make informed decisions. These individuals urgently need legal support—here in Costa Rica and also in the United States.

They deserve to have their stories heard and their humanity recognized. They are people with dreams, fears, aspirations, and, above all, the right to live in peace and with dignity like every one of us. They should never have been detained or deported. They should never have been separated from their families and loved ones. And they should be able to live safely and move freely, wherever they are.

Advocates speak with detained people through a fence surrounding the facility.

Advocating for dignity and human rights

As a Quaker organization, AFSC’s belief in the divine worth of every person calls us to act for justice. We are committed to working alongside our partners in Costa Rica—Jesuit Service for Migrants and the Center for Justice and International Law—to support the people detained at CATEM. We are working to connect them with legal representation and other support to help them return to the U.S., apply for asylum in another country, or pursue other options of their choosing.

We’re also urging the Costa Rican government to allow people to leave the facility if they choose and move freely in the country. CATEM should return to its original purpose as a voluntary shelter where migrants can get help without restrictions on their rights and freedom.

The government of Costa Rica must also refuse to accept any more deportation flights from the U.S. The Chaves administration agreed to do so in February as the U.S. pressured Latin American countries to facilitate deportations or face punitive economic measures. But there is no financial benefit that justifies violating anyone’s human rights. People seeking safety should never be bargaining chips in international relations.

In the United States, AFSC continues to join with people across the country working to stop the detention and deportation of our family members, friends, neighbors, co-workers, and community members. This work is more urgent than ever as the Trump administration expands deportations, separating more families and endangering lives.

The day after our visit to the detention center, I drove back the eight hours to San Jose. At the end of my drive, I got to hug my children in our home.

I asked myself how I felt. The answer: outraged, frustrated—but not powerless. I know my voice matters. And so does yours. I invite you to share in this outrage, to raise your voice, to do all that you can to demand an end to these inhumane practices, to start seeing each other as human beings again.