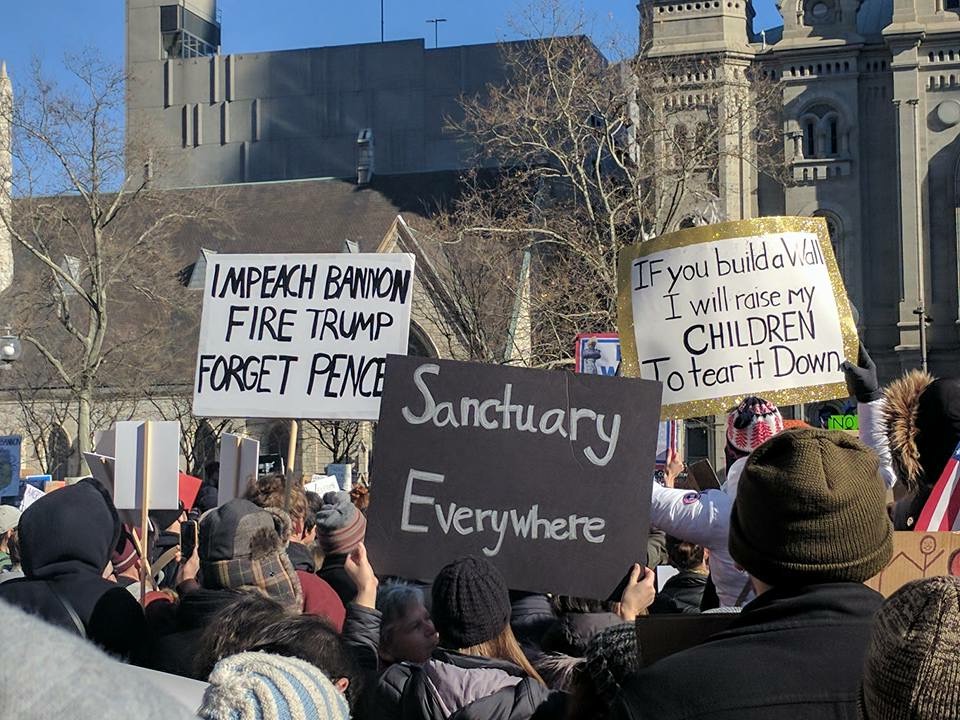

Photo cred: Lucy Duncan Photo cred: Lucy Duncan

Chris Crass is a longtime organizer, educator, and writer working to build powerful working class-based, feminist, multiracial movements for collective liberation. He is one of the leading voices in the country calling for and supporting white people to work for racial justice. He joined with white anti-racist leaders around the country to help launch the national anti-racist network Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ), which works in white communities for racial justice. Rooted in his Unitarian Universalist faith he works with congregations, seminaries, and religious and spiritual leaders to build up the Religious Left. He lives in Louisville, KY with his partner, and their two kids. Learn more about Chris here. I spoke with Chris and Richie Schulz, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting’s community engagement fellow, on September 6th, we talked about the current political moment, organizing white folks for racial justice, and the stake white people have in that work. This is the third of five posts from that conversation. This wasn’t an interview per se, but a conversation with each of us contributing.

Lucy Duncan: I wanted to move more directly into the state of Quakers and Unitarian Universalists (UU) and the work to subvert white supremacy within both faiths. I think the Quaker world is actually mimicking a lot of the larger political tensions and pushback that is happening. There's been a lot of movement, a lot of learning, a lot of shifting among Friends and we're also experiencing huge backlash to that shifting within Quaker congregations and institutions. It looks different in different places. In some yearly meetings there have been people who've been fired or marginalized inside the organization during this process of backlash. I could go on and tell lots of stories about the ways the backlash looks in different places, but it's definitely mimicking the same kind of larger, broader political manifestations.

Among Quakers there are very few people of color in the room, in Quaker spaces, and there hasn't been a real centering of their voices with some of the actions taken. There is often a very limited capacity to consider the people that are not in the room, people often most impacted by injustice, and instead there is a focusing on the needs and the feelings of the white people present and not necessarily expanding beyond that. I'm curious about your sense about where UUs are and what the movement is inside the congregations and larger UU institutions.

Chris Crass: I think within the Unitarian Universalist (UU) world there's been decades and decades of Unitarian Universalist people of color, as well as a significant number of white, anti-racist Unitarian Universalists, who, over the last 30 or 40 years have really been working on challenging white supremacy within the denomination of Unitarian Universalism.  Along with challenging white supremacy internally, UU leaders of color and white anti-racists have been working to help congregations work for racial justice in their communities and in our society. In Arizona a few years ago, the state was implementing the “Show Me Your Papers” legislation, with racist Sherriff Joe Arpaio leading the way, and Unitarian Universalist congregations in Arizona were deeply involved not only in the fight against these anti-immigrant attacks, but also had deep relationships with migrant, immigrant, Latino, Latina, Latinx-led organizing in the United States. They had built these really strong relationships, over time, and were continuing to show up at demonstrations, community speak outs, were volunteering to do logistical support, were raising money, and were turning people out to take action. The “Show Me Your Papers” went into effect, Latinx-led organizations called for a “Summer of Non-Compliance” and called on allies around the country to come and commit civil disobedience.

Along with challenging white supremacy internally, UU leaders of color and white anti-racists have been working to help congregations work for racial justice in their communities and in our society. In Arizona a few years ago, the state was implementing the “Show Me Your Papers” legislation, with racist Sherriff Joe Arpaio leading the way, and Unitarian Universalist congregations in Arizona were deeply involved not only in the fight against these anti-immigrant attacks, but also had deep relationships with migrant, immigrant, Latino, Latina, Latinx-led organizing in the United States. They had built these really strong relationships, over time, and were continuing to show up at demonstrations, community speak outs, were volunteering to do logistical support, were raising money, and were turning people out to take action. The “Show Me Your Papers” went into effect, Latinx-led organizations called for a “Summer of Non-Compliance” and called on allies around the country to come and commit civil disobedience.

I was part of the direct action planning team with local leaders from Puente, and one of my jobs was to help support UUs to participate in civil disobedience. The goal wasn’t just to have the hardcore UU activists take direct action, it was to move hundreds of UUs into various positions to help it happen, to have it be a catalyzing experience for the denomination as a whole to rise up for racial justice. Having UUs in mass take to the streets in solidarity with local Latinx-led organizing, was powerful both in its opposition to the racism of the state, but also in building multiracial relationships rooted in liberation values in action. A year later, in 2012, the denomination ended up having a general assembly in Arizona and instead of hundreds of UUs, it was thousands of UUs demonstrating for racial justice in solidarity with local Latinx-led resistance, and that had a huge impact on the congregations and really pushed a lot of people to [think], how do we actually live these values, how do we actually take more confrontational action?

The Black Lives Matter movement has had a tremendous impact on the UU denomination, from the leadership of Black UUs who formed Black Lives of UU, to hundreds of congregations participating in local and national actions for Black Lives Matter. And there has been painful struggle within the congregations about the Black Lives Matter movement. A UU leader of color in Virginia told me the story of how in her congregation installed a Black Lives Matter sign was put in the sanctuary and how there were white members who were supportive, but also some white members who said, “Well, you know, this is our sanctuary, this is where we come to escape and find safety beyond the oppression and the injustice and the news out there in the world. This is where we come to get nourishment away from all of that.” She responded that as a Latina UU, having a Black Lives Matter sign in the sanctuary actually affirms that she and her family and other UUs of color can actually find sanctuary in this space and that this is a space that didn't just affirm white lives and white bodies and white need for spiritual nourishment, but a Black Lives Matter sign in a sanctuary meant “This is our values and our sanctuary is alive in these times and focused on what matters most.”

White supremacy is deeply committed to poisoning the hearts and minds of every single white person, whether they are in a Quaker congregation, a Unitarian Universalist congregation or whether they are on the streets in Charlottesville holding up a Nazi flag. We need to be able to anticipate the way this poison operates. The backlash is devastating, the backlash is painful, particularly for folks of color who in our faith tradition see a white backlash to their dignity and to their lives. But nonetheless, the backlash is going to be a part of the process and so how do we actually use the backlash to galvanize progressive sources even more? How do we unite our people even more to live our values in the time and not let the backlash undermine our efforts? How do we do this in a way that helps us be even more courageous, more clear, more committed? How do we do this to grow our numbers even more so folks say, "Oh my gosh, I can't believe that there would be this kind of reaction in our congregation, I need to get off the side lines and start to express my support of these movements like Black Lives Matter.” We have to create as many opportunities to invite people onto the right side of history in our congregations and not expect people to already be there.

Lucy Duncan: I agree with you. And there are two things I want to speak to, one is that the whole idea that "I come here to be safe, away from the world", I think that that’s an illusion, that sense of safety. That sense of safety arises from privilege, but that privilege is harming so many and clogs up the hearts of white folks, keeps us from connecting and being able to focus on the perils of people of color, but also the perils to our own lives. Ruby Sales (a social justice activist) asks, "Why is it that white people are so concerned with safety?" People of color are never safe. It reminds me of expanded sanctuary and Sanctuary Everywhere: What we need is to bring the world into our spaces and expand our sense of what sanctuary is and where it is so that it's everywhere so that people don't need to take refuge from oppression.

The other thing, and I'm just going to tell you this very briefly, there was a very, very powerful ministry at New England Yearly Meeting this year by a young Black Quaker man, Xinef Afriam, who said: "Here is the bowl of Quaker faith and practice and what is that bowl made out of?" He said it was made out of certain good things, but it's also made out of white supremacy; given the time and place of Quaker origins, it was made of the material in that culture. "And can that bowl hold me as a Black Quaker?" And he said that the core belief in Quakerism is that there is that of God in everyone. He continued, "If the bowl of Quaker faith can't hold me as I am as a Black Quaker, then it can’t really hold God. So, whose responsibility is it to crack that bowl or reshape that bowl?" I think cracking it is important to expand the sense of sanctuary, to expand the sense of what this container is: faith and practice that can hold everybody. And he said, “And so, if we want something that holds God we must deal with the container itself.” I think that's a really powerful metaphor.

Related posts

This is the time of monsters: A conversation with Chris Crass pt. 1

The precarity and possibility of this political moment: a conversation with Chris Crass, pt 2.

Organizing white people for racial justice: A conversation with Chris Crass, pt. 5