Courage to Resist: Commemorating 50 Years Since Vietnam

As we mark half a century since the end of the Vietnam War in April 1975, we honor all who spoke out and acted on their convictions for peace. Here are just some of their stories.

Were you a conscientious objector, draft counselor, or war resister who took action with AFSC during the Vietnam War? Please use this link to share your story with us!

Christopher Meyer, war resister

I was part of the AFSC team that led the nonviolent action training of thousands of peace marshals that were positioned along the route in the 1969 People's Coalition demonstration in Washington on November 15.

On the morning of the March, we had all the marshals in the Ebeneezer Baptist Church behind the capital for a final briefing. Our permit only allowed us to be on the north side of Pennsylvania Avenue. While I was speaking, several screamed out there was no reason why we shouldn't march on both sides of Pennsylvania Avenue. That started to get a lot of people in the room jazzed up, but I saw violating the permit as a bad way to start the demonstration. I don't know how I ever had the clarity to say the following, but I recall vividly stating to the crowd “We didn't come here to take over Pennsylvania Avenue. We came here to end the war in Vietnam!" This was met with huge applause and the disruption ended.

Jane Barton, volunteer in Vietnam

“I was fortunate to be involved with the AFSC project in Quang Ngai at a time when many of the prosthetists and physical therapists were replacing the AFSC staff. A seed planted by past AFSC staff had come into fruition as Vietnamese staff assumed full time positions.

During my tenure, I was able to secretly take photographs of political prisoners who had been tortured. In 1973, when I returned from Vietnam, these photographs added witness to a major antiwar campaign highlighting how the U.S. government was funding the imprisonment of thousands of innocent Vietnamese civilians. Amnesty International and AFSC sponsored me on a speaking tour to urge Americans to take action to stop the U.S. government from funding the war. [Friends Committee on National Legislation] scheduled targeted visits to certain members of Congress. The lack of financial support of the South Vietnamese government helped end the war.”

Richard Morse, draft counselor

“Once I got to the University of Connecticut and started a postdoctoral fellowship, I reached out to the AFSC office in Cambridge around spring/summer 1967. They had a course on draft counseling and the law—probably three or four sessions. It was an hour and a half drive each way, but I took that knowledge back to the University of Connecticut and set up a draft counseling center. Together with a lawyer and a psychiatrist and a few others, we started providing draft counseling at the university.

Typically, we were seeing undergraduate and graduate students at the University of Connecticut. The counselees all seemed to be trying to work out their feelings about the war and other practical aspects. We shared various options and their implications, ranging from refusal to cooperate with the draft system altogether (resulting in jail) to other less severe options. I recall at least one person who came and shared their experience refusing the draft.

Conscientious objection included an option to perform civilian alternative service or go into the military as a non-combatant medic. Other options included joining the Coast Guard or National Guard, which would likely have kept you out of Vietnam. Some chose to go to Canada. We would provide information about immigrant status in Canada, although warned that this was typically a permanent move until President Carter agreed with not prosecuting any former Americans wanting to come back and visit family.”

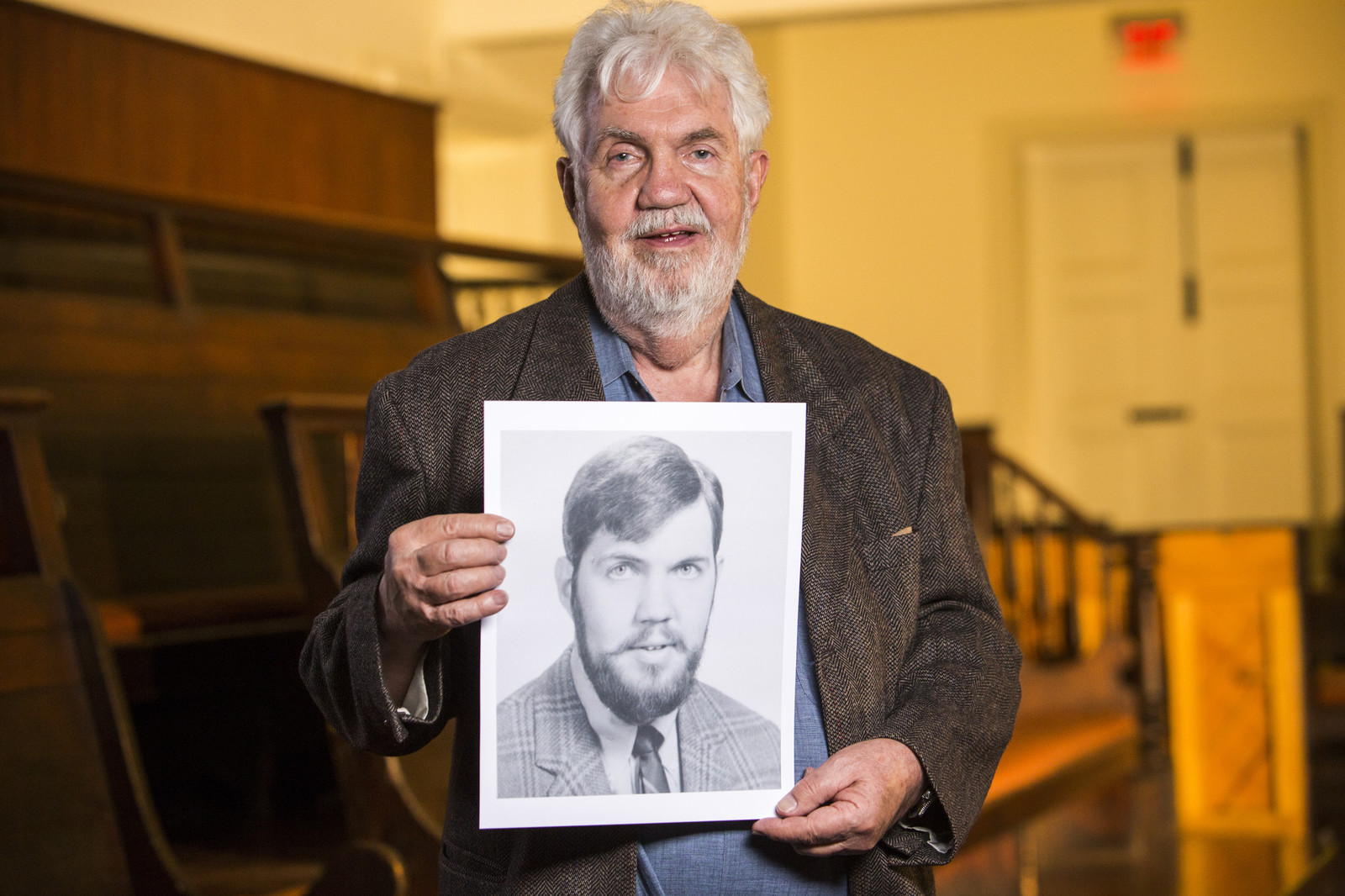

Bob Eaton, war resister

For me, resistance to the war in Vietnam took two forms: resisting the draft and providing direct medical aid to civilians on both sides of the conflict. Draft resistance was relatively easy. With the support of WWII CPS veterans and draft resisters, I left my job as Youth Secretary for the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting and, expecting immediate arrest, publicly returned my draft cards on October 16, 1966. No arrest was imminent, so I took employment with the newly formed A Quaker Action Group (AQAG).

AQAG was formed because of the failure of the AFSC to provide medical relief to both sides of the Vietnam conflict. While there was a terrific AFSC prosthetics facility in South Vietnam, the AFSC Board in 1967 balked at sending aid to North Vietnamese civilians, for the not-unfounded fear that the Nixon administration would revoke its tax-exempt status.

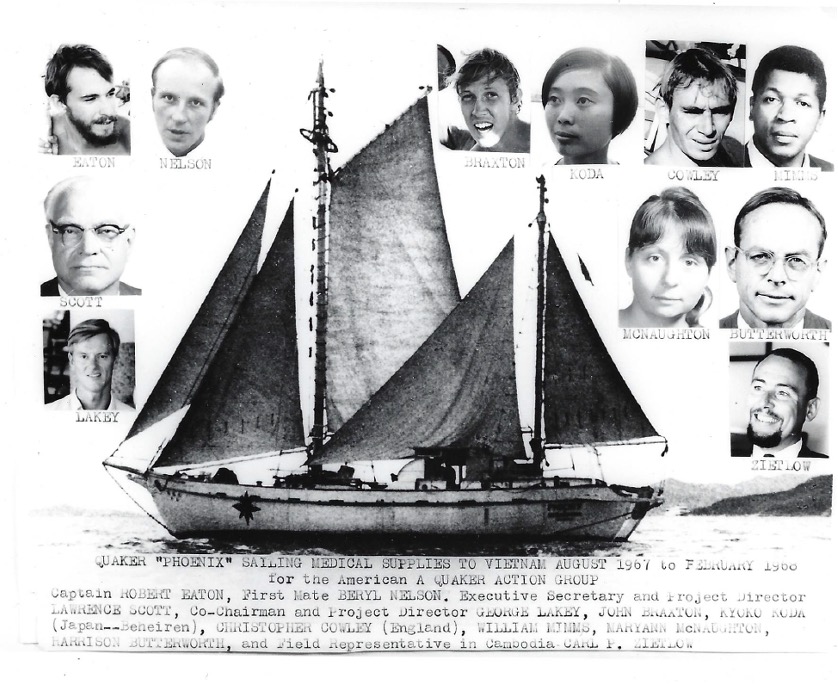

The ship Phoenix became the vehicle for AQAG to sail medical supplies directly to hospitals in North Vietnam. I served as First Mate and then Master of that ship. That took a different kind of courage than draft resistance, because there was no precedent for such an act in the middle of an incredibly violent war zone.

And that gets to the heart of the matter. Dan Ellsberg was fond of saying that “Courage is contagious.” He was right—but in my experience, the seedbed of courage is community.

The community of World War II Quaker draft resisters and CPS veterans grounded my resistance and helped me through two years in prison, along with others such as Quaker and AFSC-related people: Rick Boardman, John Braxton, and Michael Simmons. Prison visits by Bronson Clark (WWII resister and AFSC General Secretary) and Quakers Bob Horton and Faye Knopp (founder of AFSC’s NARMIC) provided a community of support that sustained our resistance. A Quaker Action Group—with Friends such as George Lakey and George and Lillian Willoughby—provided a deeply religious and happy, singing community that gave us the courage to sail a small ship into a war zone.

Lesson learned: it all begins with community—being together without being afraid.

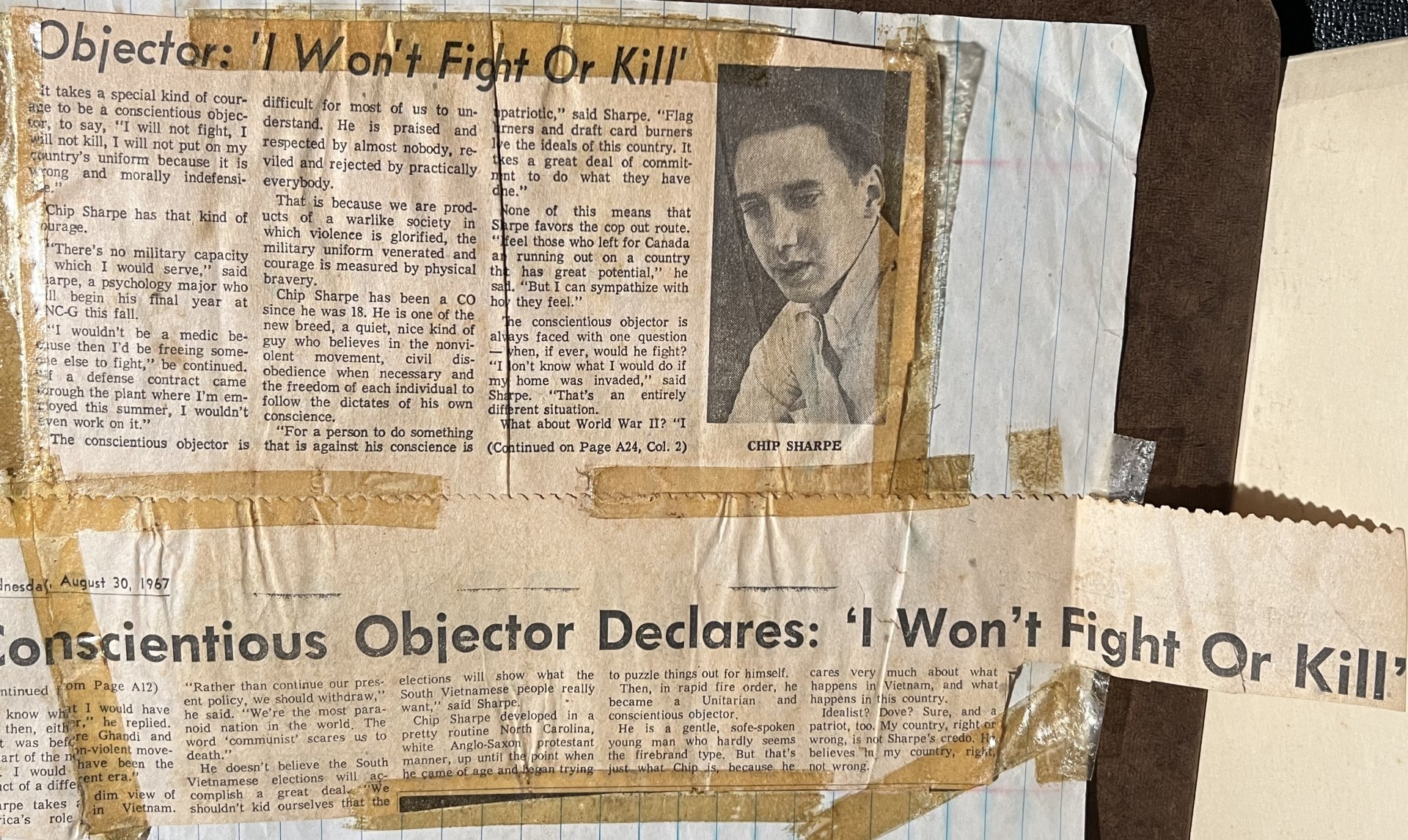

Chip Sharpe, conscientious objector

I began my two years of employment training draft counselors and producing a war resistance newsletter for AFSC’s Southeast Region in 1969. At that time, the office was in the “Blair House” in High Point, North Carolina, just 15 miles from Greensboro, where I had lived since birth (1945). Will Hartzler was Executive Secretary and Bill Jeffries was Peace Education Secretary. I had begun refusing to pay taxes for war, both the phone tax and income taxes. On the W-4 form filed with AFSC, in order to prevent IRS withholding from my paycheck, I claimed as dependents the population of Vietnam, “depending on me to end the war in their country.” Most employers would have reported such to IRS, but AFSC honored my exemption from withholding.

My success at being classified as a Conscientious Objector had been enabled by the historic and relatively large presence of Quakers in Guilford County. (Twenty miles to the south, the Ashland draft board was said to pride themselves on the fact that they had NEVER granted C.O. status to anyone.) Thus, I began my employment with AFSC already full of appreciation and admiration for the Society of Friends.

Publicized acts of young men burning their draft cards further inspired me to action. However, I was not inclined to ignite that piece of paper. (Partly due, perhaps, to having been raised to reuse and recycle material, and partly to quitting cigarettes at age twelve with a strong distaste for inhaling smoke.) Instead, I wrote a statement of my reasons for tearing my draft card into small pieces. Before ripping it, I placed the whole card near the center of my typed statement and cut a stencil with AFSC’s new and modern Gestetner. I then mailed copies, each with one piece of my draft card glued onto the image of the card, to President Nixon, Congressional representatives, and other officials. I am still very grateful to AFSC for letting me use their mimeographing equipment.

Peter Woodrow, conscientious objector

“My father was a CO in World War II. There was strain of Methodists who were pacifists. He declared himself a CO and was part of AFSC’s World War II civilian public service camps. After the war, many COs wanted to work overseas. Many volunteered for overseas service. My father then worked for AFSC in China.

In college, during the Vietnam War, I went to Oberlin. Throughout my college years, I was doing a lot of antiwar organizing, and many young men were intent on resisting the draft. There were lots of strategies that people used. All kinds of ceremonies. In my senior or junior year, people were declaring what they would do—acts of resistance. I didn’t burn my draft card, but I declared myself a resister.

It was easy for me (to apply for CO status). My agreement was that I wanted nothing to do with the military. I said, if AFSC could handle it (any follow up to the CO application), I would file the application. My draft board was in Media, PA. They had never refused a CO application. So there was no problem to get the status. I filed and was granted CO status and AFSC was satisfied. I worked for two years in Quang Nai.”

David Henkel, conscientious objector

On how I became a CO:

"I became aware of the hidden nature of the war while at Penn. A friend of mine on the soccer team was beaten by fraternity boys while he was demonstrating against chemical and biological warfare research, leading me to become a member of Philadelphia Resistance, and subsequently declined an appointment to the Peace Corps because it would have meant working for the US government. Instead I filed as a CO, trained as a draft and military counselor at AFSC, and worked as the AFSC staff member in Hawai’i. There I counseled young men who were troubled by their engagement in the armed forces in Vietnam and at home in Hawai’i. This also introduced me to being an ally to the Hawaiian land rights movement, and then led to work with the Service Committee in Southeast Asia, along with Stewart and Charlotte Meacham.

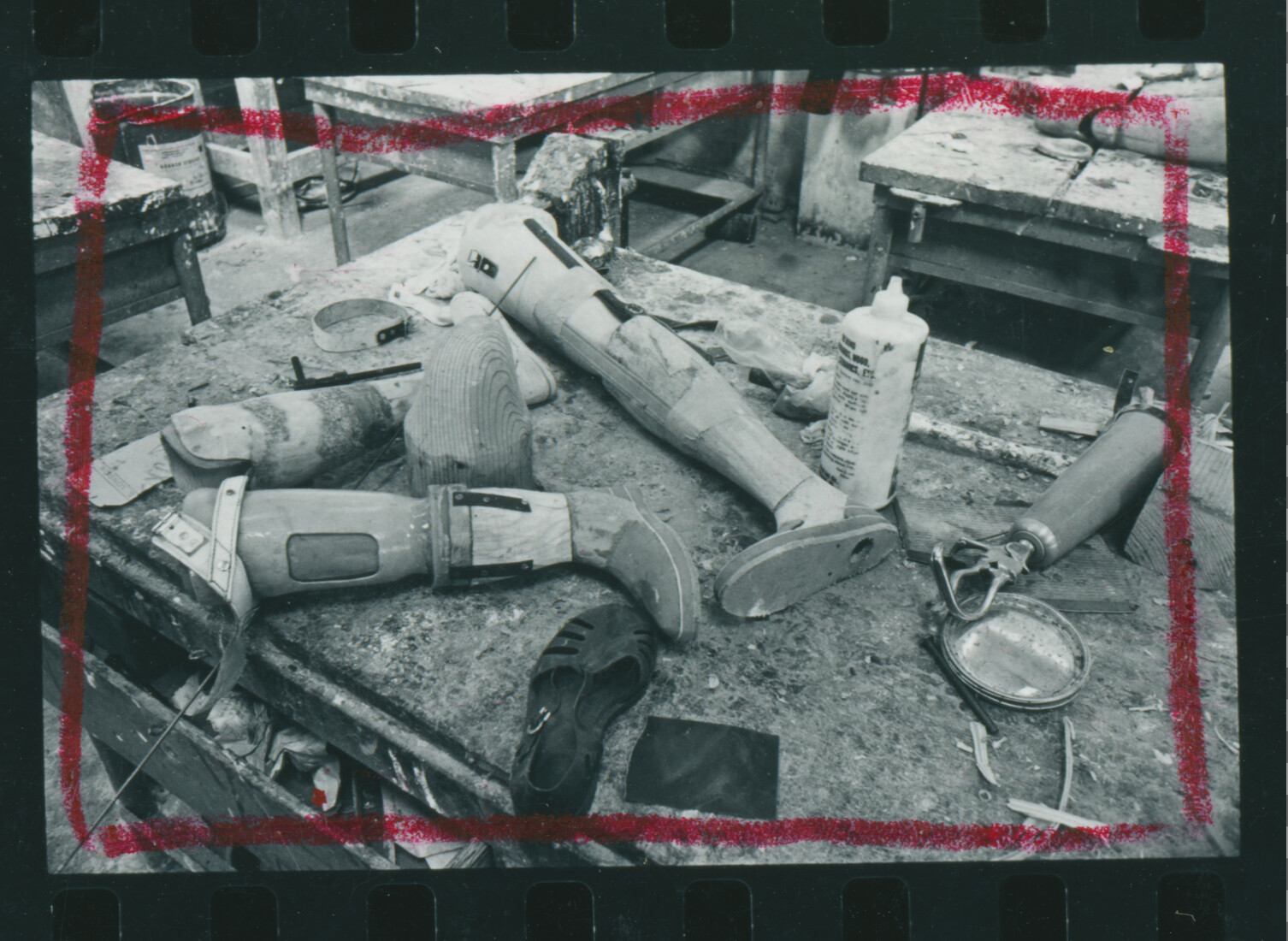

In Laos I came face-to-face with the effects of the war and with the ingenuity of local people in responding. This is a photo of a locally-made prosthesis that I have had on my wall ever since: bamboo shank, tin can ankle, rubber tire foot pad.

[AFSC’s work] resisted the evils of war and of racism, and then it supported the people who were, who are waging that battle. And so I was able to see the resistance and the support. And to my mind, both of those things have been very important to me—to be able to continue to speak out but also to lend a hand. You’ve got to be able to do both.

And I guess what I’m wondering about is as we think about what we resisted in our times, whether it was World War II or Vietnam or wherever it was, where does this lead us going forward? Because we are still a country engaged in exploiting other places and people."

Jack Malinowski, war resister

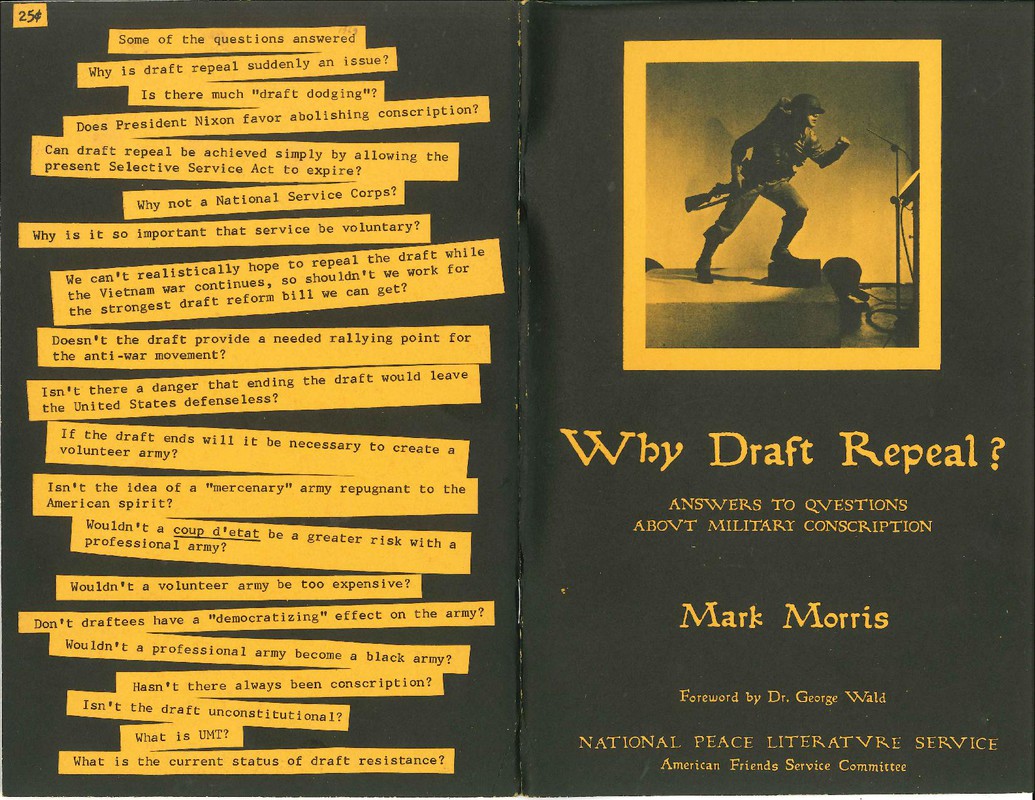

Jack was a teacher at St. Joe’s during the Vietnam War era. In the early-mid 1960s, he was involved in antiwar activities. He became a draft counselor and first encountered AFSC during that time. AFSC provided the materials and resources for him to learn how to providing draft counseling for his students.

“You just didn’t do it blatantly!” Jack said. “It was perfectly legal, as long as [I] wasn’t advocating that students break the law. The federal government had to recognize it was perfectly legal. Info is power. A lot of AFSC related people did that. AFSC offered information for draft counseling. Invaluable stuff—in those days when it was really hard, and the country was split so badly as it is now. War intensified when Nixon was elected.”

Kent Walton, conscientious objector

“On Easter Sunday, 1971, I participated in an Atlanta Quaker-sponsored public mailing of my draft card back to my local draft board, in front of Atlanta Selective Service headquarters. This was accompanied by a letter stating my refusal to recognize or accept any draft classification whatsoever. The public mailing included a ceremony where participants (12 of us, I think), compared our draft cards to Judas' holding pieces of silver to betray Jesus. This was a major media event broadcast on the evening news.

The day before, Atlanta Quakers had hosted a ‘last supper’ with David Harris, recently released from prison for draft resistance, where he explained how joining ‘The Resistance’ meant refusing any and all classification from Selective Service.

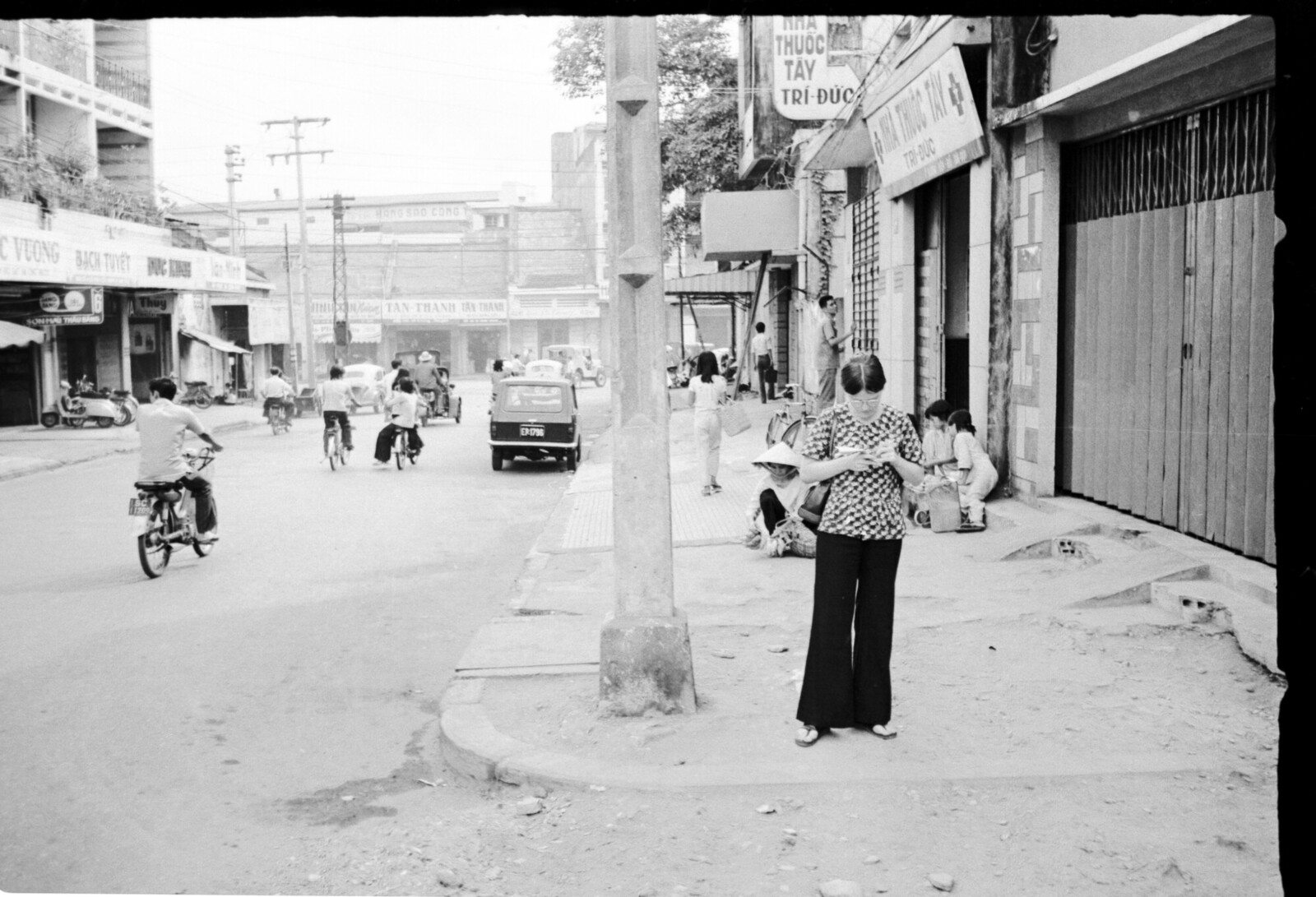

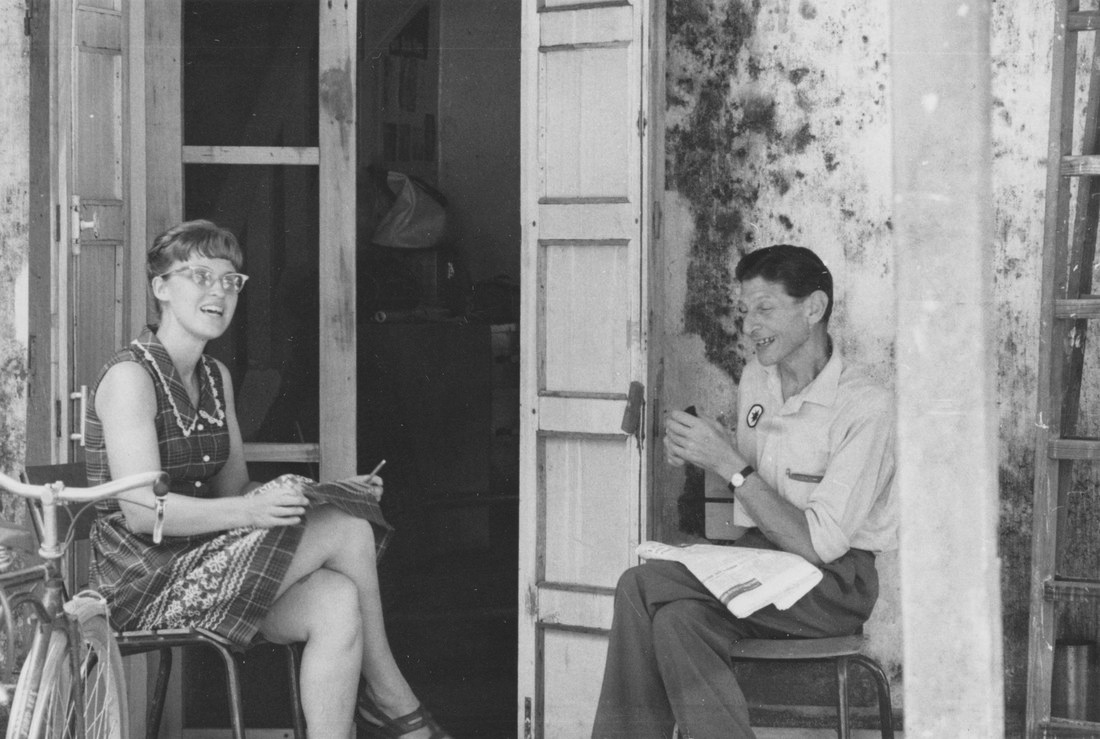

Claudia Krich, volunteer in Vietnam

I was co-director of the last AFSC team in Vietnam, with my husband Keith Brinton. I was there from March, 1973 until several months after the war ended and the new socialist government took control in 1975. Our program ran a large physical rehabilitation center, reported on the war, hosted visitors including politicians and news organizations, and wrote articles that were published in the US. The AFSC center, run since 1975 by the Vietnamese government, still exists and is located in Qui Nhon.

In 1975 our small foreign team of six made the decision to not leave with the American evacuation, so we were among only a handful of Americans (and one Brit) who stayed after the war ended. We were and are able to report what we witnessed, what actually happened in Vietnam after the Americans left and the war ended.

There were many AFSC volunteers in the Vietnam program over many years. Some came as COs, some came while refusing to comply with the draft completely, and some of us (women) weren't eligible for the draft but came anyway. I was lucky to be in the last group and to see the end of the war and the beginning of peace in Vietnam.

Dan Seeger, conscientious objector

In 1965 the Supreme Court, in the case of The United States of America vs. Daniel A. Seeger, greatly expanded the religious qualifications for allowing pacifists exemption from military service on conscientious grounds.

In the 1950s, Dan Seeger refused to register for the draft because of his moral beliefs. He was tried and convicted for draft refusal and sentenced to a year and a day in prison. But Dan remained true to his beliefs, pursuing his case all the way to the Supreme Court. Eventually, his efforts would expand who qualifies for conscientious objector status in the United States—and help safeguard the First Amendment’s guarantee of religious liberty for generations to come. AFSC and other groups supported Dan throughout this case.

“I realized I was bucking the Federal Government, and I felt nervous,” he said, “but I knew that what I was doing was right. I felt it was something that had to be done rather than collaborate in the destruction of other people’s lives.”

Marjorie Nelson, volunteer in Vietnam

“When the Vietnam War broke out, I was 24 years old and living in Indianapolis, Indiana. I was studying at Indiana University’s School of Medicine to become a doctor. I grew up as a Quaker and was a conscientious objector. As I heard about the war, I wanted to find a way that I could help. The American Friends Service Committee knew about my interest in serving overseas. And they contacted me and said, ‘Would you by any chance be willing to serve with a project we’re starting in Vietnam?’ and I said, ‘That's an answer to prayer.’”

What AFSC told me is that they had two projects in Quang Ngai province, which is in central Vietnam. The first one was a rehab center, a rehabilitation center for war-injured civilians, and we would be training local Vietnamese how to, for example, make artificial limbs and braces so that when we were no longer there, there would be skilled people who could continue to do that service.

The other program that we had then was a pre-K school for refugee children who were living in refugee camps right around the city. Then later we had a program of my going to the provincial prison across the street where we did sick calls for prisoners.”

Dina Portnoy, war resister

“I was in college in 1967. I was starting to get knowledgeable about the Vietnam War and various forms of resistance. I was in awe of people who were willing to take big risks and refuse to go into the military. It took courage, especially for people in the military, to take a moral stand against the war.

After college, I went to London and I worked for War Resisters International and then other war resistance organizations. Eventually I became a teacher because it seemed like teaching in the city was another form of working to change the world. 1967 changed me and changed my path.

Did we end the war in 1967? No. But within a year or two there were millions of people marching nationally. We got the ball rolling. [In 2016], I marched after the inauguration. It was huge and it was organized so quickly. We could never have done that back then – it took so much longer to grow the movement. People today are lucky because they are more conscious, and they have great tools for organizing at their disposal, but they also continue to have incredible challenges in front of them.”

Tony Avirgan, war resister

“After [Vietnam Summer], our group formed Philadelphia Resistance. Over the years, I was arrested 15 times. One time I ended up in jail for 30 days. We ran a printing press. We got intense media coverage. We refused to pay taxes. We held countless rallies—at one such event the police chief punched me in the face. We accompanied men to Canada. We protested with props at sporting events. We even had an infiltrator—a policeman joined our group under cover.

All of it was our way to defy, slow down, and make it more expensive for the Selective Service System to continue to operate. Each year, more and more people turned against the war. It became more and more unpopular. We found people who agreed with us in the courts and in the military.”

Ed Wujciak, conscientious objector

“Anti-war information was not easy to find in those “primitive” pre-internet times, but I did find two good resources: AFSC and the War Resisters’ League. They offered me both a vision of a world without war, and concrete suggestions on how to disassociate from, and hopefully undermine, the war machine. I felt that I was finally home. The draft counseling and information services offered by these groups were a huge help to me and countless others facing the Selective Service.”

Michael William Murphy, conscientious objector

“My involvement with the AFSC was brief, but it set into motion a chain of events that completely altered the course of my life. In the beginning of 1970, I graduated from college in Syracuse, New York. I lost my student deferment and was soon called up for my pre-induction examination. I knew I wasn't going to allow myself to be shipped off to Viet Nam: the idea of war seemed insane to me. I was prepared to go to jail if necessary.

Fortunately, there was an AFSC office in town, so I contacted them. They counseled me, helped me with my application, and recommended getting supporting letters from priests at the Catholic seminary I had attended for three semesters. Thanks to thorough preparation, my interview with the draft board was simple. All they wanted to know was, would I perform my alternative service without giving them any more trouble. I agreed.”