While many states have moved away from the death penalty, the Justice Department plans to execute five people on death row.

Update: In June 2020, the Supreme Court refused to hear a death penalty case, clearing the way for federal government to resume executions. Arnie Alpert, who wrote this piece in 2019, had worked to abolish the death penalty in New Hampshire as a staff member with AFSC.

The Trump administration's announcement that it intends to resume federal executions for the first time in 16 years flies in the face of moral values, common sense, and history. For good reasons, the United States has been moving steadily away from the death penalty – most recently demonstrated in my own state of New Hampshire, the 21st to abolish the practice.

We don’t need volumes of data to remind us why executing people – for any reason – is wrong. But the reasons to end capital punishment are many. For starters, use of the death penalty has been shown to be influenced by racism. In short, those who kill white people are more likely to get a death sentence than those who kill people of color. And of those who are convicted of murder, people of color are more likely to get death sentences than white people. The pattern includes those on death row for federal crimes and who are affected by the administration’s new policy. In the three districts (Virginia, Texas, and eastern Missouri) that account for the bulk of the federal death sentences, most of the people on death row are people of color.

For another, there is no evidence that sentencing people to death or executing them does anything to protect public safety. Years of study by criminologists researching whether the death penalty deters crime has demonstrated that we need to look elsewhere to reduce the level of homicide.

Opponents of capital punishment include family members of murder victims. In New Hampshire, one of the leaders in abolishing the death penalty was state Rep. Renny Cushing, whose father and brother-in-law were killed — in separate incidents — in the doorways to their homes. “If we let those who murder turn us to murder, it gives over more power to those who do evil. We become what we say we abhor,” Rep. Cushing has said.

The release of 166 people from death row over the decades – based on evidence that they did not commit the acts for which they were sentenced – is yet another example of the deep and deadly flaws in the criminal justice system.

The modern movement for death penalty repeal in my state began with a speech by Rep. Clifton Below in 1998, who stated on the floor of the New Hampshire House of Representatives, “When possible, we should choose life over death, good over evil, the possibility of redemption over destruction, of healing over revenge, love over hate.”

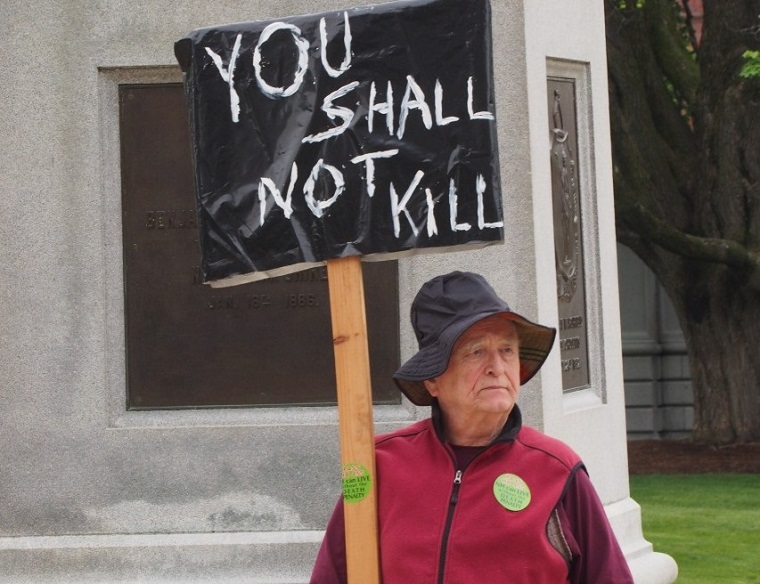

It is for reasons like these that religious leaders from many traditions have spoken out for the death penalty to be abolished.

The AFSC Board named many of these issues in a statement adopted 43 years ago. Capital punishment is “inflicted most often upon the poor, and particularly upon racial minorities, who do not have the means to defend themselves that are available to wealthier offenders,” the Board wrote. “The death penalty is especially abhorrent because it assumes an infallibility in the process of determining guilt.”

In addition, the AFSC statement said, “It is bad enough that murder or other capital crimes are committed in the first place and our sympathies lie most strongly with the victims. But the death penalty restores no victim to life and only compounds the wrong committed in the first place.”

Over the past 25 years, the use of the death penalty has declined sharply, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. “New death sentences have fallen more than 85% since peaking at more than 300 death sentences per year in the mid-1990s. Executions have declined by 75% since peaking at 98 in 1999.”

Twenty-one states now ban the practice, and, in most of the others, it is used only rarely. A movement away from the execution solution grows from changing attitudes – based on years of evidence and experience – among prosecutors, jury members, judges, lawmakers, and members of the general public. It’s time for the federal government to follow suit.