Stop killing us at Governor's mansion in St. Paul, MN Lucy Duncan / AFSC

A few weeks ago, on my way to Illinois Yearly meeting I was in St. Louis staying with friends, Steve and Sandra Tamari. While I was there, Steve took me to Ferguson. We stood on the street where Michael Brown’s body lay for hours, and visited the memorial for him embedded in the sidewalk. Steve told the story of the protests in the early days, which continued for weeks afterwards. We stood there in the sunlight as people walked by pursuing their daily lives. Next to the side walk is a manicured lawn that rises into a sloping hill. The apartments look like apartments near where I live. It felt like just a regular place.

It made me think that we in the United States have become disturbingly used to weekly, sometimes daily, police shootings and the normalization of evil. That evil isn’t anything new; it’s just now receiving much more widespread attention due to the Black Lives Matter movement and the regular recording and publication of videos of these incidents.

Steve also took me to the corner at which VonDerrit Myers was killed. VonDerritt Myers was killed by police two months after Mike Brown was killed by Darren Wilson. The family and community had just placed a memorial to him (without the approval of the city) in the sidewalk with a tree nearby. The memorial reads, “In memory of VonDerrit Myers Junior, Age 18… Let us be open-hearted and work together to appreciate each other and live in our own good nature.” While we were standing there, Myers’ cousin came up to the corner and spoke with us. He told us he was an Eagles fan, but VonDerrit had been a Giants fan. He recounted how he had gotten VonDerrit a Giants baseball cap for Christmas one year and that the following Spring, to his dismay, the Giants won big time. He paused, looked at the memorial and said, “He’s in a better place, this here is hell.”

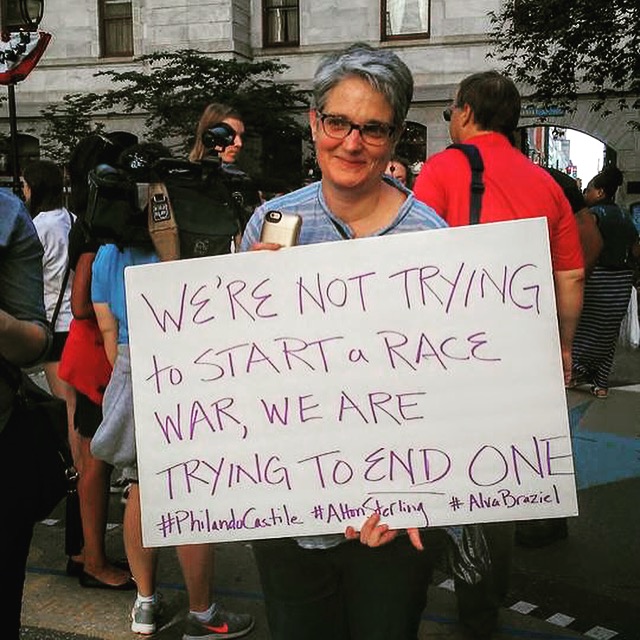

I was at the FGC Gathering in Minnesota when Philando Castile was killed by police officer Jeronimo Yanez in Falcon Heights, 75 miles away. On Friday, a car full of Quakers and AFSC staff drove to the protest at the Governor’s mansion in St. Paul. There were tents set up on easements on the edge of the sidewalk and huge signs saying “Justice for Philando,” “Stop police brutality,” “Stop killing our fathers,” and “Stop killing us.” There was an audio system, and music was being played. Black folks were dancing together joyfully. I used to dance as a child, but one way whiteness got to me was to teach me that my dancing was too open and expressive, too joyful. At the protest, I moved with the music. Black voices were centered in the space. It was good to be in a community of resistance. Later a woman spoke into the microphone, “We are grieving. We don’t dance in the aftermath of Philando’s shooting, we dance because we have survived.”

Just as the protesters danced, so many folks who are targeted by oppression resist by living with open hearts in spite of the enormous pressure and daily acts of marginalization they experience. I wonder sometimes whether white peoples’ inability to understand that for so many “this here is hell” clouds our ability to take action to end the normalization of state violence. I think a major way white supremacy hurts white folks is that it envelopes us in a comfortable cocoon that keeps us from feeling the pain (or joy) of others. What happens when we recognize that cocoon for what it is, and begin to emerge from it? What is each of us called to do?

I say, let’s dance, live with open hearts, and disrupt the evil of police violence and racism that has been with us for far too long.

Related Content

On Black Lives Matter and revolutionary love

10 ways white supremacy wounds white people: A tale of mutuality