Edward Hicks' painting Peaceable Kingdom depicting Penn's treaty with the Lenape JR P, from the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art via Flickr CC license / Public domain

Rabbi Brant Rosen, AFSC’s Midwest Regional Director, and I participated together in the Interfaith Network for Justice in Palestine initial gathering in August, 2015. Within that context there was a lot of talk of decentering whiteness and decolonizing faith as a pathway toward liberation. Decolonization disrupts and critiques the idea that European modes of thought and ways of being are the “best” or the “only” way and actively engages in opening space for multiple cultural identities, practices, and ways of thinking/being (particularly indigenous ways). Brant and I have been continuing this conversation, specifically about how decolonization relates to Quaker and Jewish faith. This transcript includes excerpts from our recent conversation. - Lucy

Lucy Duncan (LD): A really big awakening for me and part of what attracts me to decoloniality is the realization and understanding that white people lost their indigenous cultures in the construction of whiteness. I remember when I was getting more intense about wanting to be anti-racist, I was kind of in a phase of hating white people. I thought that there was something really wrong in the genes of white people that they could wage such violence on whole peoples. I wanted to distance myself from other white people and was turning that feeling inward, and I said something about this to my friend Niyonu and she said, "But Lucy, white people lost their indigenous cultures in the creation of whiteness, too." Despite the privilege that whiteness maintains, we are all hurt by the system of white supremacy, and it's really important to remember that.

That’s not to say that those of us of European descent were hurt as badly by the system of white supremacy as all those who have been targeted since, but understanding this woke me up and made me more aware of all that was lost in the process of colonization; all the wisdom, all the cultural practices, and a way of being that was more deeply in harmony with the earth. Though white folks benefit materially from white supremacy, the construction of whiteness robs us all of our humanity.

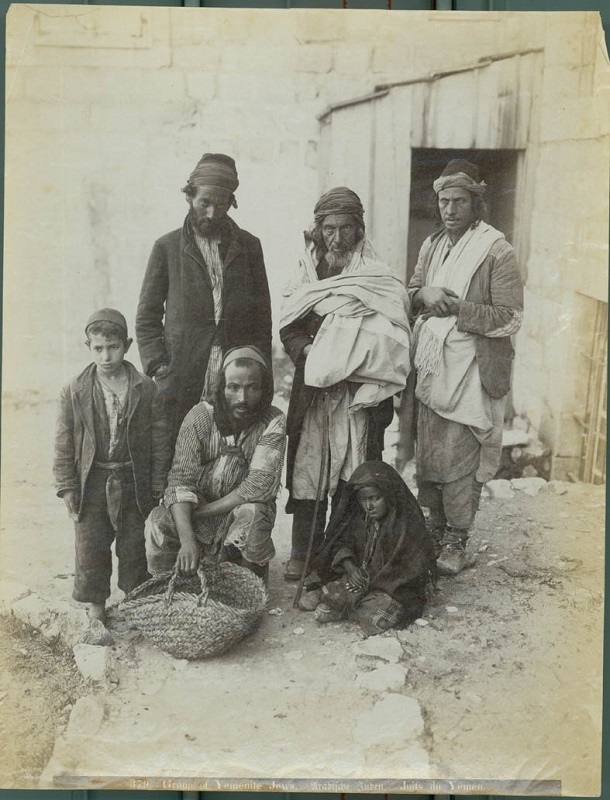

Brant Rosen (BR): I think for Jews it's even more complicated because Jews have always been a global people. Throughout the Diaspora, there are white European Jews, Middle Eastern Jews, African Jews, Southeast Asian Jews… And while in this day and age most Jews in North America are white, the number of Jews of color is increasing. I think it is safe to say that while European Jewish immigrants were seriously discriminated against, as were many immigrant groups, white American Jews today enjoy the power and privilege that comes with being part of the white majority in this country. And when you consider that the state of Israel is an ethnic nation state created by white European Jews, this just makes it all the more complex to understand one’s Jewishness within a decoloniality frame.

LD: Right, well it's kind of like white women. It’s important not to conflate oppression, but I think that there is this sort of interaction of identifying as somebody who's marginalized and oppressed and holding a position of privilege and power at the same time. As a bisexual woman who is white, I have these multiple identities and it's so much easier to identify or name the way in which I have been marginalized and claim that as an identifier than it is for me to claim the way that I hold power and privilege.

BR: And even to push it even farther, I think when we white Jews claim victim status or status of the oppressed while at the same time enjoying all of the power and privilege that comes from being white, we are able to play both sides of that coin, so to speak. But within the Jewish community, there's increasing discussion about the role of Jews of color in this equation. I've recently learned the term “Ashkenormativity” which refers to the assumption that Ashkenazic Judaism is the dominant form of Judaism. But in truth, Judaism has always been a mosaic. It's always been this multifaceted civilization that's changed and evolved and has grown in very different historic and cultural circumstances and contexts.

Yet today, when people think of Jewish foods in this country, they'll probably refer to lox and bagels and all the Ashkenazic staples. In fact, there's nothing uniquely Jewish about these foods – and certainly a Jew from Morocco or Yemen would have very different culinary associations. And so when Ashkenazic Jews make these assumptions, we make our Jewish brothers and sisters of color invisible without even realizing it. Their historical and cultural experience is very, very different. Probably one of the most telling aspects of this is the role of the Holocaust which affected European Jews, and as a result looms very, very large in the experience and identity of Ashkenazic Jews in ways that it doesn't for Sephardic or Arab Jews. And yet we assume that all Jews relate to the Holocaust in the same way. This is another example of that Ashkenormativity that the Jewish community is only starting to confront.

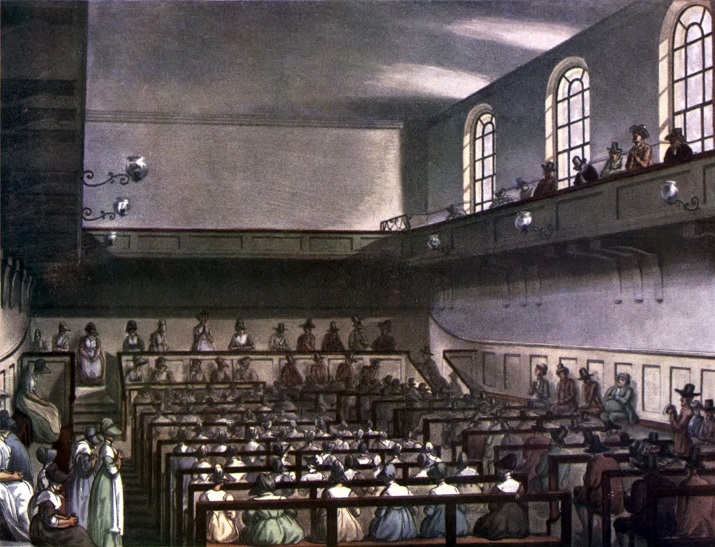

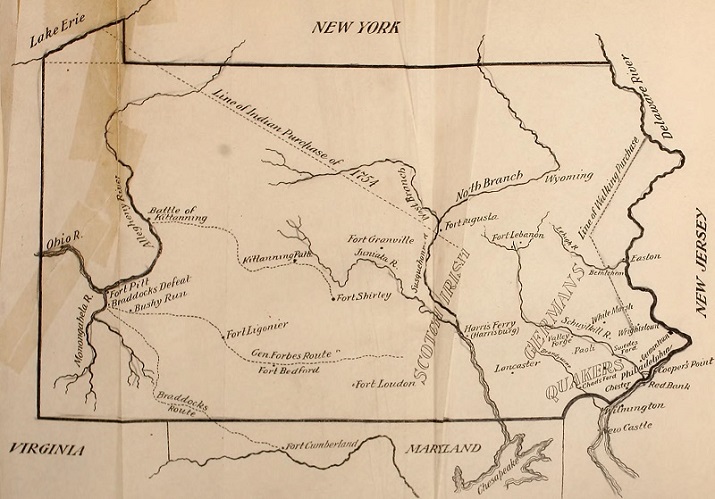

LD: Within Quakers, having been founded in England, there are pervasive European and white assumptions that permeate the faith. Quakers colonized Pennsylvania in order to get away from religious persecution in England. Many of those who first settled had been imprisoned in England for their witness against the state religion, against paying tithes.

King Charles II “granted” Penn the land inhabited by Lenni Lenape that became Pennsylvania to pay a debt he owed Penn’s father. The early Quakers established religious liberty because of the persecution they experienced, but that liberty didn’t extend to the Lenni Lenape. In the charter, Charles II said that Penn intended to, “to reduce the savage Natives by gentle and just manners to the Love of Civil Socieitie and Christian Religion.“ Penn’s reputation is as a peacemaker with the Lenape and, though the colonization of Pennsylvania was less overtly violent before the Walking purchase (carried out by Penn’s sons) and the Paxton boys, the intention was very much a part of the colonial project, which included cultural, spatial, and governmental domination. There are descendants of those early Quakers who still hold wealth and power as a result of this original colonial act, and our institutions benefit as well. What would it mean for us to really own this history, to be ready to repair the damage done by this initial act of colonization that brought Quakers to Pennsylvania?

I find very interesting among Quakers how readily we claim William Penn who was a slaveholder and a colonizer as a hero of the faith and I think that that's an example of holding onto a Eurocentric identity within the faith. Greg Elliott says, "When we're ready to denounce Penn is when we're ready to really be more powerfully faithful to the roots of what we're trying to live -- of activism and of social witness and of the original insight of Quakerism."

BR: Is that discussed within Quaker circles, the notion of denouncing Penn?

LD: In some it is, and Paula Palmer, a Quaker from Colorado, is doing quite a bit of research on Quaker complicity with Indian Boarding schools.

It was interesting, having just been at the World Plenary of Quakers in Peru there were Quakers from 37 countries and 77 yearly meetings represented. The reason there are Quakers around the world is because Quakers were missionaries and they were trying to spread the good news of Quaker faith in a traditional colonial, missionary frame. I have a friend who's a Kenyan Quaker who is wanting to throw off the U.S. and European control of the faith, and it's very clear that it's not only a sort of cultural struggle. It's also very clearly a power struggle.

Some Kenyan Quakers are fully claiming Quaker faith on their own terms and are ready to challenge the European constructs of the faith. When I mentioned developing a decoloniality training to my friend, he said, “Well bring that. Kenyan Quakers want this. We want this too." Quakers that are throwing off the European frame, these Kenyan Quakers in particular, tend to be more embracing of other marginalized identities, too, are more open to homosexuality, for example. I think that when you start down an anti-oppressive path, it opens all kinds of doors in terms of who you might welcome, who you feel connected to.

BR: I'm always fascinated when I learn more about indigenous peoples that identify as Christians and are transforming Christianity in all kinds of remarkable ways. Latin American Liberation Theology is probably the best example of this phenomenom. It’s so interesting because in its origins, Christianity in Ancient Palestine was an indigenous spiritual system, so to speak, but after Constantine it became the religion of empire and power and, eventually, colonization. And so many indigenous peoples have and still have Christianity forced upon them throughout history.The way some indigenous peoples who identify deeply as Christians yet are seeking to decolonize is just so fascinating to me.

I think Judaism hasn't had the same kind of struggle really until now. I think Zionism has changed the playing field for the Jewish community. I believe Zionism is really a kind of “Constantinian Judaism,” as the Jewish theologian Marc Ellis would say. It represents a bargain with empire, wedding religion and state power in ways that the Christian Church did for centuries. What is tragic to me is that Zionism has resulted in the establishment of an ethnically Jewish state in a land that has been historically central and important to many different religions and cultures. And in many ways I look at my own journey out of Zionism as a way of decolonizing Judaism and recognizing that Zionism at its core is a settler colonial system.

But it's not only about the political importance of decolonizing Israel, it's about coming to grips with this way that we've integrated power into our ways of thinking and seeing the world and relate to others. I think the rabbis who created Judaism as we know it following the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem were very wary of putting our faith in physical, military power. They knew that the Jewish revolt against the Roman Empire was ultimately devastating for the Jewish people.

I think this inspired the rabbis to create a new system, namely rabbinic Judaism that allowed Jews to be able to thrive and create this global, multiethnic, multicultural, spiritual sense of connection to one another. Judaism taught that God could be found wherever Jews created community in the world. Of course, often this meant living within empires – most notably Christian empires – that were very oppressive to them. But still, the concept and embrace of a Jewish Diaspora is really what kept Judaism from becoming a footnote in history.

Zionism was a very conscious overturning of this notion; a rejection of the Diaspora. There’s a Hebrew term in classic Zionist thought, shililat ha’galut, which means “negation of the Diaspora.” Zionists believed the Diaspora was an inherently inhospitable place for Jews and the only way Jews would ever be literated was when they had a nation state of their own. This was the moment when we betrayed, I believe, what made Judaism and the Jewish people so unique and special throughout the centuries.

LD: The original intention of Quaker faith was to revive primitive Christianity, and it was foundationally opposed to the equation of religion and the state. Religious liberty in the United States is derived from the Quaker settlement of Pennsylvania, but within the frame of colonization and the spread of Christian doctrine.

I wonder about the moment at which Quakerism stopped understanding opposition to the powers that be as an elemental aspect of faith. I wonder about the role of Pennsylvania, Quakers colonizing Pennsylvania and wielding a lot of power in the state and participating in the legislature until the revolutionary war, at which time most Quakers refused to participate due to the peace testimony, and so lost state power (but retained wealth and other types of power).

There's a phenomenon in which the myths about ourselves keep us from fully embracing a more radical faith. There are the Quaker ancestors that we cite like Lucretia Mott and John Woolman and all of the people that were pushing against society and pushing against their own religion while taking these incredibly brave stances. Quakers will say, "Oh, we're the religion of these people," and they take credit for those heroes or those saints but don’t always live their lives according to the pattern set by these spiritual ancestors. Quakers don’t always say, "Oh, and they inspire me to do certain things to live my faith." Many Quakers that I know who are more on the frontlines of social justice cite this initial impulse of Quaker faith; the testimonies really do call them to live one's life in a way that “takes away the occasion of war.” When you believe, really believe, that there is that of God in everyone, that’s a revolutionary idea if you take it to heart. It’s foundationally decolonial and disruptive of the status quo in terms of power.

BR: Yeah, and those are the values of Quakerism that have always attracted me and the values that allowed me to find a very natural home at AFSC. It was only relatively recently that I learned there's a multiplicity of Quakers, different kinds of Quakers just like there is a spectrum in every faith. But I've found common cause with those Quaker values because they align quite well with the Jewish values that I find the most sacred. And in listening to you talk about William Penn and the ways that Quakers bought into power when they came to the United States or the nascent United States, it's not un-similar for Jews too. there’s a mythic narrative that we tell about American Jews that we've always been at the vanguard of social justice movements, and we were involved in the Labor Movement and Civil Rights Movement and that's all true to a certain extent, but it’s not the whole story.

Judah Benjamin, a prominent Southern Jew in the 19th century, was a very high ranking official in the Confederacy. And so the truth is always as you say, a lot more complex. The story that we tell around the Passover table is our central sacred narrative and the one with which we identify the most: we were once slaves and thus we need to lead the charge in freeing slaves and the oppressed. But what does it mean when we align ourselves with state power? I'm sure this was true for the Quakers that you referred to as well. I think when you have the opportunity or access to power, it’s an intoxicating thing and it can be very hard to resist. And once you buy into it, you become part of that system, and you become in some ways part of the problem. You become Pharaoh, so to speak.

LD: And there's a lie you can tell yourself that was likely true for Quakers in early Pennsylvania, which is, "Well, we're going to do this governing thing better." In some ways that may have been true, but who are you disenfranchising in the process? How real is equality when you have built your presence on the colonization and eradication of another people? What responsibility do Quakers hold now to confront that history, name it, tell the truth of it, and make repair for the damage done in the process of our colonization of Pennsylvania? I believe this is an elemental question of faith and integrity, essential to really living up to our Quaker light.

Related Content

A rabbi at AFSC: Quaker and Jewish connections, part 1

Living our values: Quaker and Jewish connections, part 2

A fully awake theology: Remembering what we used to know