Jiddu Krishnamurti, one of the great spiritual teachers of the twentieth century, was giving a talk to a group of children, and a little boy was brave enough to ask, “What is the difference between meditation and concentration?” Krishnamurti replied, “Do you really want to talk about that? Or is it a game? Or just fun to talk about something I might be interested in? Is that it? You really want to know what is meditation and concentration? Alright, sir, if you really want to talk about that, will you pay attention to what I’m going to say?” The children all replied immediately with a polite, “Yes sir,” and Krishnamurti replied, “Don’t say, ‘Yes, sir,’ and fidget. Do you really want to talk about it? If you do, it is a very, very serious subject.”

I often think of Krishnamurti’s challenge when I’m trying to follow Spirit: Do I really want to go where Spirit is leading me? Am I actually willing to commit myself to whatever Spirit asks? Or is that just what I’m supposed to say because of my religious tradition?

I really relate to the children who replied with an automatic, “Yes sir.” Before I really knew what it meant to follow Spirit, I knew I was supposed to say “Yes.” But no one in my Quaker meeting ever told me what that really meant. They didn’t warn me that saying “Yes” to Spirit is no idle thing – it’s not just “fun to talk about.”

In my experience, Spirit’s path leads away from that which my white, middle-class culture cherishes the most: safety. Even when it appears that Spirit is leading me down a well-worn path, it’s usually a cover up, a creative way to get me to go somewhere I’d rather not go, internally or externally.

Following Spirit feels inherently dangerous to me. My mother would always say, “I just want you to be happy.” But what she really meant was, I just want you to have a good education, a satisfying career, a life partner, a stable salary, and a home in a quiet neighborhood. I’ve realized as an adult that my parents were not actually trying to pass on what they understood about happiness. They were trying to pass on what they understood about survival.

Underneath their desire for my happiness was the knowledge that this society crushes the hopes, dreams, and lives of millions (even billions if you want to think globally) every single day. They didn’t want that for me. They didn’t want me to experience the trauma of imprisonment, or homelessness, or lack of health insurance, or hunger, or poverty, or no savings for retirement. They were trying to protect me.

But following Spirit does not guarantee the kind of happiness, safety, or comfort my parents wanted for me. Spirit offers something else entirely.

And again I hear Krishnamurti: “Do you really want to know?”

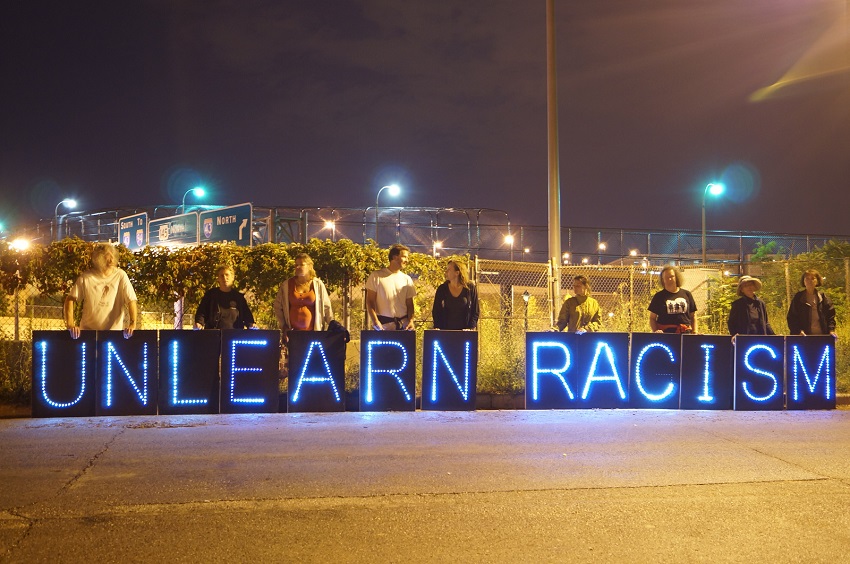

In my visits to three large, unprogrammed Quaker gatherings this summer, I saw business meetings and smaller groups struggling to follow Spirit in matters of racial justice. I believe that Spirit is calling all Friends to the cause of racial justice (all people for that matter), and I believe that most liberal, unprogrammed Quakers would agree. What we don’t agree on is how to go about it. So more times than not, we agree to disagree. When “that of God in everyone” turns into “every opinion is valid,” we’re swimming through murky waters.

In witnessing the struggles of these Quaker bodies, I realized that what Spirit is asking us to do and what we are willing to do are two very different things. Quaker process, fear, white privilege, and white fragility all play a role in preventing decisive change and transformative action. Clarity gets watered down, and all we’re left with is a vague notion that Spirit is calling us to do something – we’re just not sure what it is.

“Do you really want to know?”

Prisoners across the country, right now, are engaging in the largest prison strike in US history. At the same time, the protectors of water and land gathering at Sacred Stone Camp had their first victory in their efforts to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline, and they are only getting started. Last month, the Movement for Black Lives released a detailed list of policy demands for reparations and one of their coalition partners plans to lobby congress this week. And on September 12, faith-led coalitions in 30 state capitals delivered the Higher Ground Moral Declaration to their governments, demanding a revolution of values.

These are exciting developments, to say the least. They inspire. They renew the Spirit. And most importantly, actions like these are shaking the very foundations of injustice in this country.

Of course the forces these movements seek to transform, upend, and replace are also rallying. It seems that every day brings a new story of ecological and human disaster brought on by the insatiable violence of those possessed by white supremacist, hetero-patriarchal, colonial greed who appear hell-bent on destroying life as we know it, all for the only thing they hold sacred: money.

In times like these, we shouldn’t have to wonder where Spirit is leading us, at least not in a general sense. Instead our question becomes, how far are we willing to go? Spirit is asking all of humanity to meet this moment with the strength, courage, humility, and love it requires. What does the Quaker tradition say about following Spirit’s path?

“Do you really want to know?”

In a way, I think Quakers have never fully recovered from the tragedy of James Nayler. A very popular and enthusiastic contemporary of George Fox, Nayler was known as a powerful preacher, and even preached against slavery in the 1650s. But he is still most known for the “Bristol event” in which he rode into Bristol naked on a donkey, reenacting Jesus’ entrance into Jerusalem before he was crucified.

For his “crime,” Nayler was branded with the letter “B” on his forehead, narrowly escaped execution, was forced to do two years of prison labor, and became the first Friend to be disowned by Quakers. From James Nayler’s Wikipedia page: “The Society's subsequent move, mostly driven by Fox, toward a…more organised structure, including giving Meetings the ability to disavow a member, seemed to have been motivated by a desire to avoid similar problems.”

Perhaps Nayler took the message to follow Christ a bit too literally, but he was not wrong about the Spirit of the message. The decision by Fox and his followers to tighten the reigns on Quakerism following this event pushed our prophetic leaders to the margins of Quakerism, and we’ve never allowed them back to the center. Instead of radical faithfulness at the core of Quakerism, meeting membership and Quaker process took its place.

But Spirit is calling us. All of us. Do we really want to know where Spirit is leading us? And if we say “Yes”, is our “Yes” like the children’s “Yes, sir,” automatic and polite? Or is our “Yes” deep enough and profound enough to shake us from all the “No’s” that we cling to so desperately?

I want to know.

Related Content:

Extraordinary political opportunity for Quaker legacy of vision

Liberating Faith: a conversation with Rabbi Brent Rosen on decolonizing Quaker and Jewish practice

The Third Reconstruction: Moral fusion politics & working for justice